Nudity, Art, Sex and Death – Tasmania Awaits You

With one big bet, an art-loving professional gambler has made the Australian island into the world’s most surprising new cultural destination

Even by Australian standards, Tasmania feels strange and remote. Lost at the continent’s southeastern tip—quite literally, down under—the island is a hauntingly beautiful expanse of gnarled forests and rugged mountains, where exotic flora and fauna have thrived in windswept isolation. Its colonial history verges on the gothic. As if the Australian penal colonies weren’t harsh enough, the British settled Tasmania in 1803 as a holding pen for its worst criminals—a gulag within the Antipodean gulag, whose convict work camps were renowned for their cruelty. By the 1820s, settlers were embarking on a brutal frontier war with the Tasmanian Aborigines, whose last members were rounded up and removed to a smaller island, Flinders, where they died of disease and despair in one of the most shameful chapters in British history. Since then, Tasmania has stubbornly remained the least developed and least populated state in Australia, enduring unkind jokes among mainlanders, who often regard it as a refuge of hillbillies and yokels on a par with the stereo typed Appalachian here. Its main attraction for visitors has been its savage natural beauty, luring adventure travelers to raft its wild rivers and hike the succulent expanses of temperate rainforest in its national parks.

In recent years, however, Tasmania has begun to enter a surprising new era, as the former backwater has developed a fiercely independent cultural scene. Author Richard Flanagan, from the city of Hobart, has hit the New York Times best-seller list with novels such as Gould’s Book of Fish and Wanting. Postmodern architecture has flourished, with a string of award-winning eco-lodges poised in wilderness areas. Travelers can now spend two days hiking along a deserted coastline to the Bay of Fires Lodge, a sleek designer retreat perched on a remote headland and surrounded by wild bush. Another spectacular lodge, called Saffire, opened two years ago by the Freycinet Peninsula; its main building is designed in a flowing form that evokes the pattern of the waves, with enormous picture windows facing a string of raw mountains called the Hazards. The island’s pristine environment has attracted armies of gourmet food producers, and it now exports everything from organic wagyu beef to abalone, wild duck, brie, oysters, goat cheese, truffles and saffron. The Tamar Valley in the north is producing some of Australia’s most prized wines. And there is a general obsession with all things healthful. In fact, Tasmania can sometimes verge on Portlandia, where every body product seems to be made from an elaborate homegrown concoction such as lemon eucalyptus with wild bush passion fruit.

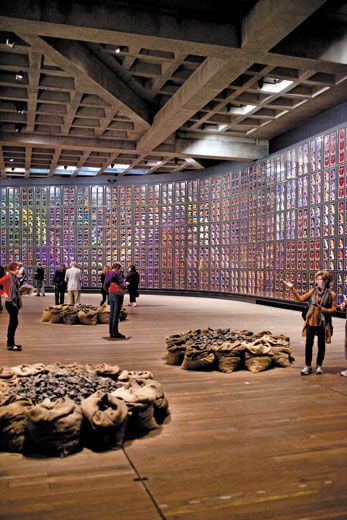

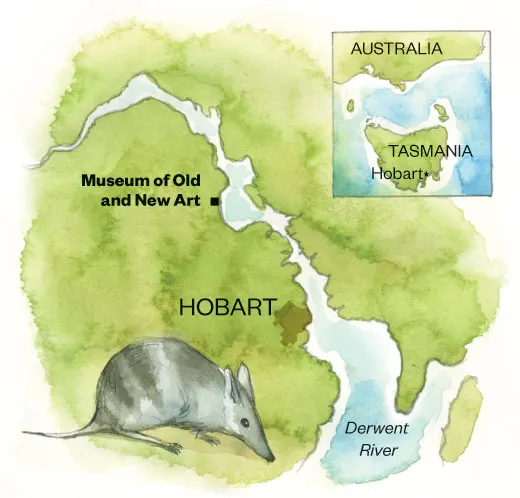

Still, none of these fashionable upgrades quite prepared mainland Australians for MONA, the Museum of Old and New Art, a radically innovative institution that opened on the banks of the Derwent River in January 2011. One of the largest private museums in the Southern Hemisphere—and without doubt the most provocative—MONA has suddenly vaulted Tasmania onto the international cultural map. Its $100 million private collection focuses heavily on themes of sex and death, and is presented in a uniquely creative setting, a purpose-built $75 million edifice that challenges our notions of what an art museum should be. There are none of the traditional “white cube” gallery spaces. Instead, laby-rinthine passageways and Escher-like stairways connect three underground levels. There aren’t even labels on the artworks. Visitors are each given an iPod touch called the “O” that permits random exploration; the device tracks your location and provides written commentaries, including poems and personal meditations. No audio commentary is provided; instead, the “O” plays appropriate music.

Some artworks with religious and sexual content have caused controversy elsewhere, which has helped make MONA hugely successful. In its first year it received 389,000 visitors, far outstripping staff predictions and making it Tasmania’s biggest tourist attraction. The museum has been a boon for the fragile local economy—officials talk of the “MONA Effect” the same way Spaniards do of the “Bilbao Effect”—and has been embraced by Tasmanians, who refer to it as “our MONA.” Its success has caught the eye of cognoscenti from New York, Tokyo and London, and stolen the thunder from Sydney’s and Melbourne’s more established art scenes, forcing even the most skeptical outsiders to accept that the island has more to offer than scenery and convict ruins.

Garnering at least as much attention as MONA itself is the man behind it, David Walsh—a mysterious multi- millionaire who was largely unknown to the Australian public 18 months ago. Walsh, 50, hardly fits the mold of a typical art patron: Raised in the working-class suburbs of Hobart, he is a mathematical savant who dropped out of college to make his fortune as a professional gambler (his empire is still funded by computerized betting, mostly on horse racing) before indulging his real passion, art. Since then, he has fascinated Aussies with his irreverent pronouncements—he delights in taunting the art establishment, describing his museum as “a subversive adult Disneyland”—and his eccentric behavior. In the Australian press, he is invariably referred to as “reclusive,” “enigmatic,” a “hermit millionaire” in the style of Howard Hughes, and is notorious for his aversion to interviews, randomly backing out at the last minute.

In fact, it was this possibility I was dreading after flying straight from New York to Hobart to meet with Walsh. He is reported to suffer from Asperger’s-like symptoms—telling a German art magazine that as a child he was “internal to the point of autism”—and is apparently difficult to lure into conversation, often staring into space or simply walking away from journalists he doesn’t like. By the time I arrived, I felt like I was on a journey to meet an Australian Kurtz who lurked somewhere up the Derwent River.

When I first visited Tasmania’s tiny capital in the 1980s, it was like a ghost town; nothing seemed to have changed since the Depression era, when local boy Errol Flynn abandoned it for Hollywood and London. Now I hardly recognized the place. From the Henry Jones Art Hotel—a former Georgian warehouse that has been renovated into luxury accommodations with exhibits of local artists in every corridor and room—I strolled via endless galleries to the Princes Wharf, which has long defied any form of progress. It was now taken over by MONA FOMA (Festival of Music and Art), sponsored by Walsh and organized by the celebrated Brian Ritchie, former bass player for the Violent Femmes who moved to Tasmania in 2008. The whole city seemed to be in ferment. Restaurants were packed; crowds thronged the sidewalks; the live music lineup included PJ Harvey and the Dresden Dolls.

Had Hobart actually become...cool?

“MONA has changed the culture here,” said Christine Scott, curator at the Henry Jones Art Hotel. “A decade ago, Tasmania had no pulse, but now young people are staying.” Walsh also subsidizes theater, art scholarships and public installations, leading to wry jokes that Hobart should change its name to Mobart. “He’s a remarkable man,” says Peter Timms, one of Australia’s top art critics, who lives in Hobart. “He has almost single-handedly transformed the cultural life of the state. Not many people can say that.”

Because Walsh seemed to exist beneath the radar for so long, rumors about his shadowy life as a gambler and his sexually charged art collection still shroud him in mythology. Friends in the Australian media told me he had been paid $250 million by Asian casinos to stay away. (Untrue; he prefers computerized gambling.) Another said that Walsh has a private apartment within MONA with one-way mirrors on the floor, so he can wander about naked and secretly observe visitors. (Also untrue; he does have an office inside, but part of its floor is regular glass.) Walsh now qualifies as Tasmania’s top celebrity. “I love his philosophy,” said Scott. “I love his arrogance.” When I said that I planned to meet him, everyone from taxi drivers to high-ranking tourism officials wanted to know the details—probably wondering, in reality, whether Walsh would turn up.

But before I could meet the man himself, I needed to get a sense of his bizarre brainchild, so I decided to make a preliminary visit to MONA, incognito.

If you’re going to confront sex and death—or even just the art world’s latest depictions of them—you might as well do it naked. This notion was cheerfully explained to me by a fresh-faced attendant when I first arrived at MONA and noticed that an after-hours “naturist tour” was on offer. Apparently, participants would be escorted through the subterranean exhibitions while in the state that nature intended. The guide would also be naked, of course. Even the guards would be naked. Since many of MONA’s artworks deal with the intimate workings of the human body, any naked viewer’s involvement would surely be at a heightened level, the attendant said. “Of course, the tour has been booked out for weeks,” she shrugged. “But I could put your name on the waiting list.”

On the assumption that getting a place was all but impossible, I agreed—giving a false name, just in case I decided to back out entirely.

Of course, when I passed by a couple of hours later, the attendant waved me over. “Looks like the waiting list is going to clear!” she chirped. Evidently, quite a number of people who’d signed up had gotten cold feet at the last minute.

“Oh, great,” I said, then made a beeline for the museum bar.

MONA was turning out to be more adventurous than my wildest predictions. I was still delirious from jet lag, and had just taken a catamaran nine miles up the Derwent, which was disorienting enough. Blinded by the sparkling water, I felt the mundane world slipping away for a more vivid dimension. Suddenly, MONA had appeared on a headland like a ziggurat of concrete and rusted iron. From the jetty, I had climbed a steep stairway designed (Walsh has written) to evoke Mediterranean sea journeys, when ancient travelers would ascend to a temple to give thanks for a safe voyage. Walsh has called MONA’s design, by Melbourne architect Nonda Katsalidis, “deliberately underwhelming,” eschewing the usual pomp of art museums, with their grand entrance halls and facades. In fact, the stairway left me standing on MONA’s roof—the whole museum is excavated from the sandstone riverbank—where the entrance is a wall covered with distorting mirrors. Walsh also owns the surrounding eight-acre peninsula, so visitors are also invited to wander off and explore his vineyard, tapas bar, wine-tasting room, boutique brewery and high-end restaurant, or stay overnight in one of eight gleaming, art-filled guesthouses.

Now I was about to get way out of my comfort zone. My 40 fellow adventurers and I descended a spiral staircase to the museum’s most subterranean level and stripped off in a dimly lit theater. Followed by two naked staff members, we awkwardly reconvened beneath an indoor cliff of golden sandstone. I noted that the group was evenly split between men and women, thankfully representing all ages, shapes and sizes. As everyone wondered where to put their hands (and their eyes), the guide, Stuart Ringholt, helpfully explained that we should consider ourselves to be part of a conceptual artwork, which explores “issues of embarrassment and self-consciousness.” He then led us through a series of galleries, past works of art ranging from the playful to the disturbing: X-ray images of entwined lovers, enormous bronzes made from interwoven figures of Christ on the cross, a passage lined with bordello-style velvet curtains ending up with graphic sexual videos and a statue of three dismembered young men hanging from a tree.

Walsh’s collection was curated with the assistance of international art experts such as Mark Fraser, a former managing director of Sotheby’s in Australia, and others are involved in MONA’s temporary exhibitions. (Jean-Hubert Martin, formerly director of the Centre Pompidou in Paris, is curating a June show.) There is no overt order or link between the artworks. In fact, one of the most original elements of the collection is its eclectic range: Placed among the contemporary pieces are ancient artifacts, creating juxtapositions that leap across millennia. A sarcophagus and mummy are part of a multimedia installation with an Andres Serrano photograph, for example. Other modern installations include Roman coins and Babylonian cuneiform tablets.

Being naked certainly kept me on my toes: Randomly encountering nude people in a shadowy maze is hardly the usual museum experience. It was disconcerting at first, but I’ve never been more alert to the art itself. Walsh clearly has a taste for the provocative. One of MONA’s treasures is British artist Chris Ofili’s Holy Virgin Mary, which in 1999 inspired New York’s then-mayor Rudolph Giuliani to threaten to cut off city funding to the Brooklyn Museum when it was displayed, for its use of elephant dung and pornography on an image of the black Madonna. Other pieces include Gregory Green’s Bible Bomb #1854 (Russian style), where a multimedia “bomb” is hidden inside a copy of the Bible. There is a huge close-up of a bullet wound, urns filled with human ashes, rooms lined with 150 plaster casts of female pudenda. Giuliani, one imagines, would have a heart attack. Still, other artworks are less confronting than whimsical. Austrian sculptor Erwin Wurm’s Fat Car is a red Porsche whose lines bulge like a bloated stomach. A giant indoor waterfall by German artist Julius Popp spells out words that are searched each day on Google.

After an hour of exploring darkened galleries, I finally began to relax about being naked—then we stepped into a brightly lit laboratory-like room. This was where an artwork called Cloaca was maintained. A mass of pipes and glass tubes combined with chemicals, it is able to reproduce the workings of the human digestive system. Museum staff “feed” Cloaca daily, then collect the odoriferous result 13 hours later. But it wasn’t the evocative smell that was shocking. The room was lit by harsh neon lights, and each wall was lined with mirrors, which reflected our images into infinity. Suddenly, there was nowhere to hide. We were visible from every angle. After this clinical episode, nobody had any energy left to be self-conscious. When we all ended up in the bar at the end of the tour, we stood around and chatted casually, still nude.

If that’s not an ice-breaker, I don’t know what is.

The next day, I met Walsh’s research curator, Delia Nicholls, at MONA’s outdoor café and confessed that I’d actually visited the museum the day before.

“Yes, I know you did,” she said. “You went on the naturist tour.”

I blanched. But how would she know?

“We saw you on the security video.”

I had a vision of the MONA staff sitting around with cocktails, laughing uproariously.

“David is interested to meet you,” Nicholls added.

This was promising news. But when I returned to the lobby for my appointment at 12:30, Nicholls looked harried.

“I don’t know where David is,” she muttered, before calling him on her cellphone. I overheard the conversation.

“Yeah, I’m not there, I’m here,” said a gruff voice.

“Where’s here?” she asked.

“I’m not telling you.”

Nicholls shot me a wan smile. “Never dull.”

But minutes later, we ran into Walsh charging at full tilt across the museum roof. He was an unmistakable figure, looking like a middle-aged rock star with his wild silver hair streaming down to his shoulders, sport jacket, distressed jeans and sunglasses.

“You mind if we do the interview in the car?” he asked me distractedly. It turned out that he had double-booked and needed to travel into Hobart to see an experimental modern opera. “You’re driving,” he added.

I started the engine and tried to ease into the conversation. (Nicholls had confided to me, “the important thing is to engage him.”) I’d heard that Walsh’s first passion was antiquities, and I’d once written a book on the ancient Olympic Games. So I began by asking about his classical Greek collection. Soon enough, on the highway to Hobart, we were swapping ancient coin stories. He owned an array from Bactria and Athens, and a single coin from Syracuse is the most valuable antiquity in MONA.

It was a fertile starting point. Walsh explained that his interest in numismatics—indeed, his philosophy of museums—began to develop at age 12. He had decided he was an atheist, so every Sunday morning, after telling his Catholic mother that he was going to church, he went instead to the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, which combines art, history and natural science, and became intimate with oddities such as the bones of a wombat-like dinosaur the size of a rhino, Byzantine coins, and relics from prehistoric Antarctic forests. At the time, his mother was raising him single-handedly in one of the poorest parts of Hobart. “When I was young, the idea of my life turning out as it did would have seemed insane,” he mused, “a fantasy within a kid’s head.”

Walsh’s prospects improved suddenly in the early 1980s, when some friends at university decided to pool their talents for mathematics to beat Tasmania’s Wrest Point Casino, then the only legalized casino in Australia. They had limited success, Walsh explained, but in the process they figured out how to make steady sums from computerized horse racing. (Gambling is not taxed in Australia; one of Walsh’s partners, Zeljko Ranogajec, the son of Croatian immigrants, is today believed to be the world’s biggest gambler, placing $1 billion a year in bets.) Walsh began collecting art by accident. He was traveling in South Africa with a gambling friend in the early ’90s when he discovered that the government forbade visitors to take out of the country more money than they brought in. He had $18,000 extra cash when he saw a Nigerian wooden door for sale—“a beautiful thing” that cost $18,000. Inspired by his older sister, a Hobart artist, Walsh soon began expanding his collection in a contemporary direction as his gambling fortune grew.

In 1995, he purchased the riverside winery where MONA now stands and four years later opened a small museum of antiquities. “It looked great,” he said, “but it also looked like every other museum in the world, with schmick [cool] white walls and restrained white cabinets. I wondered: Why did I end up building the same museum as everybody else?” Very few people came. So he decided on a radical renovation.

The interview had to wait as I parked the car, and we dashed into an old church that had been turned into an avant-garde performance space. Inside, a bohemian crowd was sitting on the darkened floor among dangerous-looking metal sculptures. A hush fell as we entered, and I heard people whispering, “There’s David Walsh.” We were joined on the floor by Walsh’s girlfriend, American artist Kirsha Kaechele, who began massaging his back and feet. We were then treated to an ambitious musical piece that featured discordant operatic singing accompanied by piano, cello and Brian Ritchie on the shakuhachi, a traditional Japanese bamboo flute.

I had no idea whether this marked the end of our meeting, but after the concert, Walsh suggested we head to a restaurant. He kept talking as he strode through traffic—topics included an esoteric account of how a scientific principle about electromagnetism called the Faraday Effect pertains to modern advertising—and kept up the intense pace after we took a table, continuing without pause for the next two hours. (I later learned that press portrayals of Walsh as a “recluse” receive snorts of derision from those who know him well. As one friend told me: “A dude who hangs out in bars every night of the week and will talk to anyone who approaches him is not reclusive.”)

With MONA’s high-tech gadgetry, whimsical flourishes and relentless hipster irony, the museum seems to challenge visitors not to take it seriously. But Walsh explained that before he commissioned its design, he toured Europe and the United States to refine his ideas. “The great repositories of Western civilization, such as the Metropolitan Museum in New York, are amazing, but you basically get what you expect,” he said. “There’s nothing that has the capacity to change you or who you are. MONA gives you no appropriate cues about what to expect, so there’s no mind-set we’re driving you into. I’m trying to give you the capacity to explore and engage individually.”

Walsh argues that his eclectic, personal approach harks back to the era of the Wunderkammer, or Cabinets of Wonders, which would be kept in the private houses of aristocrats from the Renaissance onward to reflect their own tastes. Fine artworks were displayed alongside religious relics, mythological marvels and natural history treasures such as gems, shells or fossils. “In the Wunderkammer, they wanted the mystery to be maintained,” he says. “Their unicorn horns didn’t have labels. They were just objects of wonder.” The cabinets fell out of favor after the popular revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries, and were replaced by grand national museums like the Louvre, which lay their exhibits out in orderly fashion. (Survivors of the cabinet spirit include Sir John Soane’s Museum in London and the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia. But there has also been a recent revival of interest in the approach, including the Museum of Hunting and Nature in Paris, “Le Cabinet de Curiosités” exhibit curated by Thierry Despont in New York last November and recent exhibits at the Venice Biennale. The Museum of Jurassic Technology in Los Angeles is another, although with an ironic, self-referential twist.)

“There is a sense where I’m trying to build an anti-museum,” Walsh summed up, “because I’m anti-certainty. I’m anti-the definitive history of the West. MONA is experiential. It’s not a product. It’s not a showcase. It’s a fairground.”

Such pronouncements make established curators’ skin crawl. One prominent New York expert refused to even be quoted in case it “validated” MONA’s approach, arguing that the unqualified combining of different period pieces is little more than an expression of a collector’s rampant ego. But other critics suggest that any shakeup of the museum world is not entirely a bad thing. “Much of contemporary art is not serious,” says Hobart-based critic Timms, “but most museums haven’t cottoned onto that yet. The art is given a reverence that isn’t really justified. It’s put up on a pedestal, and people object to that—they feel they are being conned. At MONA, art is entertainment, it’s cabaret, it’s theater. MONA is the world’s first no-bull art museum that says to people, ‘Don’t worry, have fun.’ I’m not sure that’s a good thing, or the sign of a healthy culture, but it’s honest!” He adds: “Of course, a concern is that the more serious artworks there could be trivialized.”

As for his collection, the emphasis on sex and death is natural, Walsh says, since “all art is motivated by the desire for one or the avoidance of the other. If you went to the Louvre, and explored the works that depicted sex or death, the percentage wouldn’t be any higher than at MONA. If you went into a church, the percentage that depicts death is vastly higher. Sex and death are not my theme. They’re the motives for artists, yes.”

Still, Walsh admits that he was surprised by the positive response to MONA: “I did expect a fundamentalist backlash.” Walsh’s friends say that the museum’s popularity has obliged him to revise his contrarian attitude. “David really built MONA so he could enjoy it himself,” says Brian Ritchie. “He didn’t think it would be embraced. In fact, he thought he would be reviled for it. I think he was even a little disappointed when he wasn’t! Now he’s moving into a different way of looking at it. He’s enjoying its success.”

Walsh could have built his museum anywhere, but he stayed in Tasmania, he says, partly because his two daughters from two marriages live there. But he also sees the island’s remoteness as an advantage: “When you travel to something, you’re invested in it more. If I’d built MONA in New York, I would have gotten a lot more visitors. But there’s too much background noise. The glib little jokes that MONA makes would have been lost in the clamor.” When pressed, he admits he wasn’t unaware that there might be a “MONA Effect” for Tasmania. Although statistics have yet to be gathered, he estimates that his museum added 120,000 visitor nights to Hobart in its first year, pumping $120 million into the beleaguered economy. (Walsh himself is losing $10 million a year, but he says he expects MONA to break even within five years.)

The most significant effect may be psychological. “I think it is changing how Tasmanians see themselves and their world,” says novelist Richard Flanagan. “It is liberating.” According to Peter Timms, “Tasmanians had a self-image problem. They had assumed, right from the beginning of their history, that important things happened elsewhere. But MONA makes people realize that what they do matters, and is admired by others.” The museum crops up in almost every conversation in Tasmania, and has become a prime topic in debates on how the island should manage its future. While the state government still subsidizes the mining and forestry industries, the traditional staples of the economy, conservation forces have been gaining strength ever since the world’s first political Green Party was founded in Tasmania in 1972. According to Hobart-based environmentalist (and Ritchie’s wife) Varuni Kulasekera, MONA proves that there are more viable and creative ways forward: “David is employing 200-plus people, and bringing thousands of tourists to Tasmania, who then fill hotels and restaurants, creating even more jobs,” she says. “There’s not a lot of spinoff activity from a wood-chipping plant.”

On my last night in Hobart, I went to another Walsh-commissioned theater production, a modern opera entitled The Barbarians that was performed almost entirely in Greek. I sat cross-legged on the floor in a packed theater, which was filled with smoke and pierced by lasers. A naked male dancer emerged from a water-filled trough and began gyrating feverishly to a shrill chorus, as synthesized music echoed through the air.

It was intense, but I expected nothing less. This was Tasmania, after all.

Australian-born, New York-based writer Tony Perrottet is the author of five books, most recently The Sinner’s Grand Tour. Photographer Joe Wigdahl lives in Sydney.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)