How New York City Is Rediscovering Its Maritime Spirit

The city’s waterfront fell into dangerous decline, but now its on the rebound with a new wave of money and creativity

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c9/57/c95709df-7f8c-4286-a42e-b2beaeb44a0c/may2017_k16_waterfront.jpg)

“Jump in!” came a shout from the yacht’s cabin. “You won’t grow a third eye.” This is not what I wanted to hear as I was poised on the bow of a Catalina, working up the courage for a midnight dip. It was a perfect summer’s night: The dark waters were mirror-flat, and the steamy air wrapped the deck in a velvety embrace. But this wasn’t an idyllic corner of the French Riviera, Turkish coast or Adriatic. Two hundred yards away loomed the Statue of Liberty, her golden torch casting a shimmering reflection in the Hudson River.

“We’re at the cleanest place to swim in all of New York Harbor,” continued Avram Ludwig, the unflappable captain of the yacht and self-described “urban explorer,” as he secured the anchor between Liberty and Ellis islands, the Manhattan skyline glittering behind us. “There’s no river traffic, no barges, no industry.” Even better, the ocean tide was coming in, he enthused. Still, the half-dozen other passengers, Broadway actor and actress friends of Ludwig (whose day jobs are movie producer, director and novelist), eyed the river warily and cracked jokes about dead bodies floating past. The unsavory nature of the New York waterways has been an integral part of American urban lore since the 1920s, when industry closed the estuary’s many oyster beds, floating swimming pools and bathhouses. Woody Allen joked that German submarines would sneak into the bathing area of Coney Island beaches during World War II, only to be destroyed by pollution. An entire “Seinfeld” episode revolves around Kramer’s mad plan to swim in the East River and the noisome odors he begins to exude.

“Sure, I remember when I was a kid seeing toilet paper and condoms floating from the discharge pipes at 72nd Street,” admitted Ludwig, who berths his yacht every summer in Chelsea. “But now there are 14 wastewater treatment plants, and it’s completely safe.” The main problem in New York, he added helpfully, comes after heavy rains, when the storm drains overflow and bacteria levels spike—but skies had been clear for a week.

There was nothing more to be said. I took a deep breath, plunged headfirst off the bow, then began breaststroking toward New Jersey.

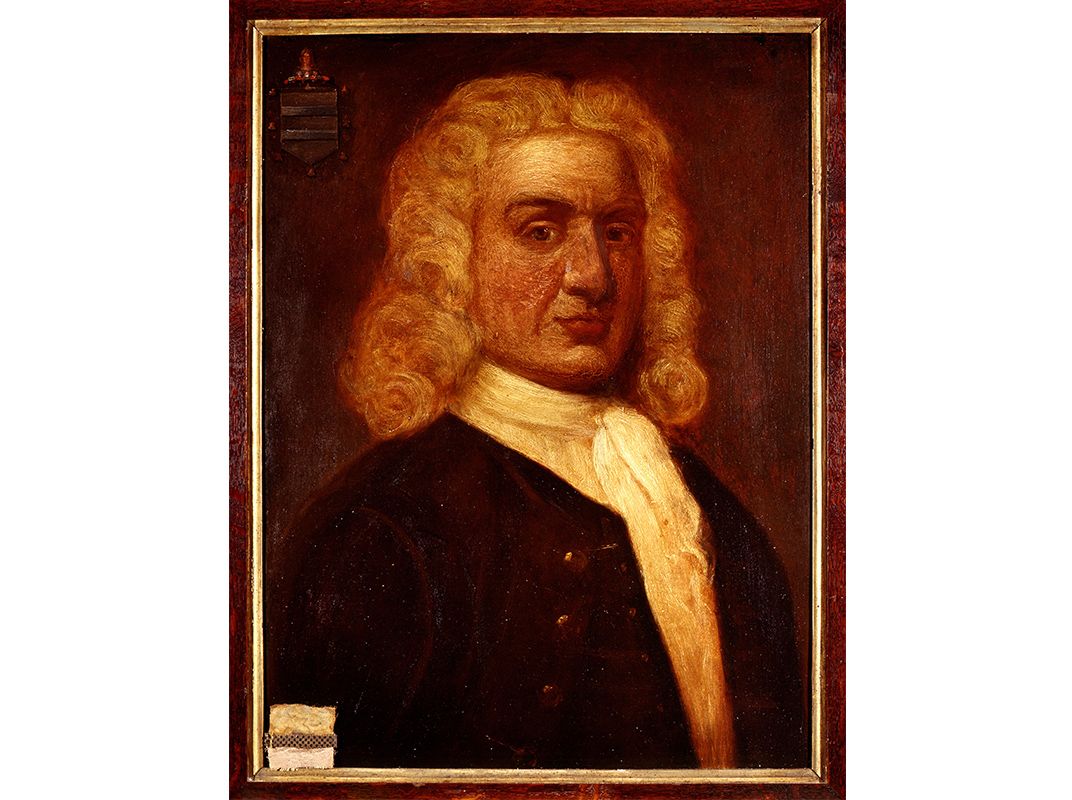

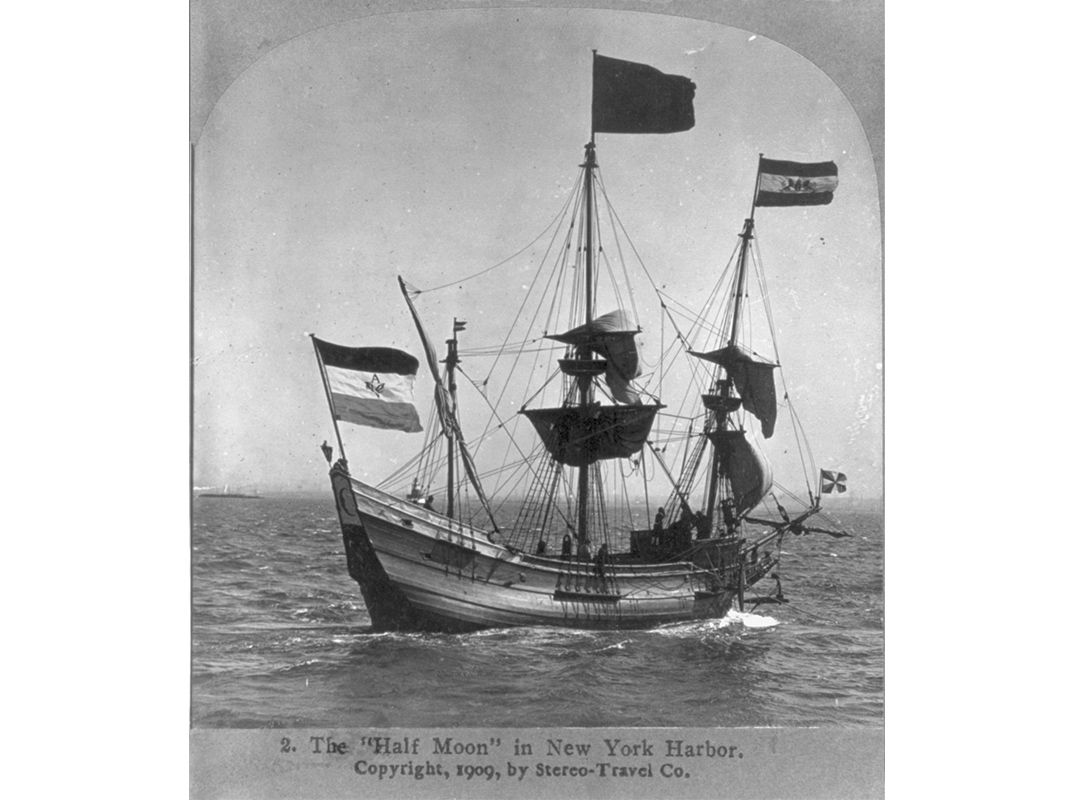

I didn’t emerge with any disturbing rashes, fortunately. In fact, it was an unlikely moment of liberation: I felt like one of the Lenape Indians, whom the explorer Henry Hudson reported came out to greet his vessel the Half Moon in 1609, “some in canoes, some swimming.” As the Statue of Liberty loomed above me like the Colossus of Rhodes, I was enjoying a water-level view that very few have seen since before Calvin Coolidge was president, when swimming from piers and pleasure boats was commonplace.

And like many New Yorkers rediscovering the water these days, my relationship to the urban environment would never be the same again.

**********

When I first moved to Manhattan in 1990, it was easy to forget that New York City is a collection of islands (of the five boroughs, only the Bronx is on the mainland) or that it has over 520 miles of coastline, more than either San Francisco or Seattle. Even harder to remember was that New York Harbor was once the busiest in the world. The depictions of Herman Melville and Walt Whitman when the shores were a forest of masts with hundreds of ferries and watercraft of every size sweeping around the city every day, seemed up there with the fantasies of Jules Verne. The Hudson and East river warehouses were abandoned, the piers collapsing, the once-thriving naval bases derelict. I would stroll from my apartment on Tenth Street east or west and find it a struggle to physically reach the water. The fabled “insular city of the Manhattoes,” as Melville called it in Moby-Dick, didn’t so much end at the waterfront as crumble into a tangle of peripheral highways cruised by prostitutes, and lots for impounded cars. The only effort at evoking the glorious maritime past, the South Street Seaport, was a cheesy mall.

Today, that dismal vision seems like ancient history. Not only have billions of government dollars been pumped into cleaning up the waterways, but starting in the late 1990s, dozens of projects large and small have began to jolt the moribund waterfront back to life. The Hudson River Park led the charge in 1998, transforming the western shore of Manhattan into a band of greenery with bike and jogging trails, playgrounds, gardens and a miniature golf course. Its success has inspired a string of ambitious renovation projects around the city, including landscaped parks on both the Manhattan and Brooklyn sides of the East River, revived ferry services and such exotic future plans as a $170 million artificial island to replace a broken-down pier in Greenwich Village. In 2010, the administration of Mayor Michael Bloomberg drafted a ten-year plan for the waterfront that has won national awards, making New York a model of urban renewal.

Today, it is hard to keep track of all the creative new developments, which in the anarchic spirit of New York, are often the uncoordinated efforts of state and city departments, private enterprise and eccentric individuals. Which is why, immersed in the Hudson River, my own summer project began to take form. Traveling only by water, I would reconstruct the saga of this legendary shore, untangling the elements of its current revival. In the process, I hoped to get a different view of New York itself, a city that until recently has preferred to destroy its history without pause or regret. I would soon find that the water attracts a theatrical cast of characters obsessed with the past—amateur archaeologists, passionate sailors, artists capturing vanishing maritime sites, and naturalists who dream of the Edenic landscape that F. Scott Fitzgerald called in The Great Gatsby “a fresh, green breast of the new world.” With a little prying, the journey would lead me into forgotten maritime worlds that even lifelong New Yorkers have no idea exist.

**********

“We like to call the waterfront ‘New York’s sixth borough’ these days, but really it’s the first borough,” observed Joshua Laird, the commissioner of the National Parks of New York Harbor. (There are some 20 sites.) “It predates the city, and allowed it to thrive.” To get a sense of this prelapsarian land, he suggested I head to the Gateway National Recreation Area in Brooklyn —“America’s only wildlife refuge that can be reached by subway,” Laird added.

Squeezed into the A train in the more densely populated corners of Brooklyn, I found it hard to imagine how the concrete jungle must have looked to Hudson 408 years ago, when he weighed anchor off “the Island of Many Hills,” which Native Americans had inhabited for some 10,000 years. As Eric W. Sanderson points out in Mannahatta: A Natural History of New York City, the explorer had stumbled across an ecosystem more diverse than the Amazon or Congo basin today. Its shores were thick with forest and teeming with foxes, beavers and wildcats, and so many frogs and birds that it was difficult for newcomers to sleep from the noise. The first Dutch fur traders who founded New Amsterdam in 1624 marveled at the “sweetness of the air,” the gentle beaches thick with oysters and waters brimming with fish.

Now, as I made my way from the subway to Jamaica Bay, part of a unique urban national park bordered by the Rockaway Peninsula and complete with its own campground, the centuries peeled away. In fact, I might have been in backwoods Maine, gazing across an expanse of water fringed by marsh and dotted with islands, except that a row of housing projects extended along one distant shore of the bay and 747s were streaming into JFK Airport on the other.

Adding to the elemental feel, a summer gale from the Atlantic was whipping the bay. “You game?” asked John Daskalakis, a Bensonhurst-born park ranger, as we squinted out at churning waves. To get to the most natural spots, Daskalakis said, we’d have to kayak across a mile of open water against the 11-mile-an-hour head wind. Soon, as we crashed through the spray, Daskalakis yelled happily: “You can feel the tension of city life just slipping away!” Back in the 1800s, these islands supported a population of around 1,000, Daskalakis added, beloved by fishermen and duck hunters, and we would have been dodging industrial barges. There was even a short-lived artist’s colony here in the 1930s. (“The lack of drinking water got them. Artists aren’t terribly practical.”) But as the quality of the bay’s water degenerated, commerce died out. In 1972, the near-bankrupt New York City donated the barely inhabited expanse to the National Park Service.

Half an hour later, we scrambled onto a sand spit covered with saltwater marshes called Ruffle Bar. These islands and their freshwater creeks and ponds are a crucial habitat for migrating birds, many of which descend here from the Arctic Circle in winter. As we explored, egrets and cormorants swooped overhead, Canada geese flew by in formation and horseshoe crabs scuttled in the sandy shallows. “Nobody realizes how wild it is out here,” Daskalakis said. “It’s remarkable how much nature exerts itself right in the middle of Brooklyn.”

With a little encouragement, the wild is also surging back to other improbable city corners, too. In 2003, the New York Restoration Project, founded by the singer Bette Midler, restored five acres along the Harlem River in the hardscrabble neighborhood of Inwood. The Sherman Creek Park now offers native woodlands, salt marsh and wetlands. This year, ground will be broken on the Haven Project on the South Bronx riverfront, creating a similar slice of green in the poorest congressional district in the nation. “The Hudson Estuary used to be one of the most productive ecosystems on the planet,” says director Deborah Marton. “The landscape is resilient.”

It’s a perception shared by many New York artists, who are lured to the rivers to create site-specific works. Not long after my Jamaica Bay adventure, I cycled past Pier 42 on the East River and spotted Jennifer Wen Ma at work in an empty slice of waterfront by the abandoned Fulton Street Fish Markets. The Beijing-born Wen Ma was painting plants with black Chinese ink, which made them look petrified. “The ink is charcoal-based, so the plants can breathe and continue to grow,” she explained. As summer progressed, tender green shoots would poke through the blackness, showing the irrepressibility of nature. The living artwork also served as “a metaphor for people living under the strain of contemporary life,” she added. In the weeks to come, it also seemed a symbol for New York’s entire shoreline as it creeps back from the brink of decay.

**********

From the start, New York depended on sea trade, although the memory is often hazy in the city’s unsentimental push toward development. In today’s Financial District at the southern tip of Manhattan, the original Dutch cow trails from the docks have now become the crooked streets between skyscrapers. A few quixotic relics of the colonial era do survive. One can visit what is thought to be the oldest paved lane in the city, Stone Street, whose gravestone-shaped cobblestones known as “Belgian blocks” arrived from Europe as ships’ ballast, or the site of the pirate Captain Kidd’s mansion. Nearby are the remains of Lovelace’s Tavern, a bar owned by a British governor that operated from 1670 to 1706, whose foundations are now visible through glass set into the sidewalk.

By the mid-19th century, New York was exploding with commerce and well on its way to being the busiest port in the world. Wharves extended up both flanks of Manhattan and across Brooklyn, and the rivers were thick with ferries and other watercraft. To get a sense of the era’s raw atmosphere, I contacted the New York Nineteenth Century Society. The members suggested we meet at the Dead Rabbit Grocery and Grog, a saloon on Water Street—which, as the name suggests, marked the original shoreline, where clippers from around the world once tossed their gangplanks. Founded by two Belfast boys, the bar evokes Irish immigrant watering holes, with sawdust on the floor and whiskey punch served in teacups.

The Society does nothing by half measures: a half-dozen members turned up in full period dress, the men in woolen waistcoats, monocles and top hats, the women in bustle dresses and bonnets. “Respectable people would never have come to these dock areas,” observed the secretary, Rachel Klingberg, as she settled her voluminous skirt to the bemused stares of the barflies. “It was dangerous, it was dirty, there were gangs and river pirates everywhere. In fact, there were really only two reasons to come here, booze and prostitutes.” As she spoke, another member in a bowler hat, Denny Daniels, produced a collection of maritime relics from his traveling antiques exhibition, the Museum of Interesting Things—a pocket telescope (“the GPS of the 19th century”), a hand-cranked phonograph that played crackling recordings of sea chanteys, and a ship’s foghorn, whose earsplitting blast made the bar clientele jump at regular intervals. At one stage, the group paused to embed a lead weight into a sailor’s knot called a “monkey’s fist,” which was used as a bludgeon by the street gangs. “It’s still illegal in New York City!” Klingberg rejoiced.

As we walked outside in the eerie fluorescent glow of glass towers, the members mourned “the fire of 1835” as if it had occurred yesterday. We ended up at the Bridge Cafe, one of New York’s oldest waterfront taverns, which has been boarded up since Hurricane Sandy flooded much of the shore in 2012; not far across the highway, the South Street Seaport was closed for a more commercial reason, a multimillion-dollar face-lift funded by the Howard Hughes Corporation, with plans for upscale boutiques and restaurants by the likes of Jean-Georges Vongerichten. It has been quite a transition for the neighborhood. In the 1850s, hoodlums from the nearby Five Points area roamed after dark, and the taverns were home to such reprobates as Hell-Cat Maggie, who supposedly filed her teeth to sharp points, and bouncers with names like Eat ’Em Up Jack McManus—semi-mythic figures who populate Herbert Asbury’s raucous history The Gangs of New York and the even more hallucinogenic Martin Scorsese film. The result, says Klingberg, was a contradictory vision of the waterfront. “New Yorkers could never quite shake their attitude to the docks as a setting for vice and crime,” Klingberg concluded. “In the 19th century, the city thrived on trade. But Fifth Avenue became the city’s most glamorous address because it was the farthest possible spot away from the rivers.”

To glimpse the hidden depths of New York’s waterfront history, the members suggested I get permission to visit a site truly frozen in time: the abandoned hospital of Ellis Island, a ghostly 22-building complex hidden beyond the famous immigration hall where over 12 million arrivals to the United States were processed from 1892 to 1954. As any schoolkid—or at least anyone who has seen The Godfather Part II—knows, teams of American doctors would check every passenger for contagious diseases, and quarantine the ill in a special clinic. (Young Vito Andolini, mis-registered as “Vito Corleone,” is detained for smallpox.) Today, the complex is decaying in Gothic grandeur. After separating myself from the ferry crowds, I sought out John McInnes, a retiree with a silver goatee who was fresh from guiding a private tour for the actor Robert De Niro. McInnes handed me a hard hat and led me past the sign screaming STOP! Do Not Enter. “Once you pass this point, you are trespassing,” he warned. Even park rangers cannot visit without permission.

The hospital is in a state of “arrested decay”—but arrested just barely. The corridors are filled with broken glass, fallen plaster and dead leaves, and many off-limit rooms are riddled with black mold. As we walked, birds swooped past us; at several points, trees were growing through shattered windows, and in one case, poison ivy. An eerie silence enveloped us. (“You don’t have this much solitude anywhere else in New York. Maybe not in the entire Northeastern USA.”) The haunted ambience was deepened by artworks in the shadows. Enlarged photographs of the original patients, nurses and doctors were placed at key points by the French artist known as “JR.” The gaze of the century-old figures are disconcertingly direct and mournful, revealing the anguish of patients who had been separated from their families and dreaded that they would be sent home. “JR said that he sensed tears throughout the entire complex,” McInnes said.

We ended up in the isolation ward for the most serious cases, with private rooms offering spectacular views of the Statue of Liberty, as well as “spit sinks” for tuberculosis sufferers. “The better the views you had of the statue, the less likely it was you would be allowed in to the U.S.,” he said. “Or that you would survive.” But despite the tragic aura, the most striking thing about the hospital today is how humane it was. The state-of-the-art facility, based on a design by Florence Nightingale, offered free health care to every third-class immigrant, many of whom were peasants who had never seen a doctor in their life or eaten such nutritious food. Of the million or so patients who stayed here, only 3,500 died; the vast majority were granted entry.

“Their first taste of America was the kindness of strangers.”

At the other end of the Gilded Age social spectrum, New York’s waterways began to be used for leisure. Robber barons would berth their luxury sailing craft uptown for cruises to the sybaritic shores of Long Island Sound. Even for the less pecunious, floating baths were built, oyster barges clustered by the piers, elevated trains ran to the beaches of Brooklyn and pleasure steamers toured the rivers. Today, the return of that water-loving recreational spirit is exemplified by Governors Island, a strategic piece of real estate that was for centuries the preserve of the U.S. military and Coast Guard. Lined with Victorian barracks and officers’ mansions dating back to the Civil War, the vast majority of it was sold in 2003 by the federal government to the people of New York for $1. Since then, it has become the setting for art shows, concerts, literary festivals and “Retro Nouveau” dance events.

Without doubt, the most theatrical step into the past is the annual Jazz Age Lawn Party. As the heat of August gathered, I headed to a ferry terminal in the splendid Battery Maritime Building, a Beaux-Arts confection of cast iron, colored tiles and stained glass, where hundreds of New Yorkers were converging from nearby subway stops in 1920s garb—the men in vintage spats and bow ties, the women in slim flapper dresses, with knee-length beads and cloche hats. Only minutes by water from downtown Manhattan, Governors Island has an otherworldly air, a car-free oasis where the only sounds on the trails are lapping waves and the tinkle of bicycle bells. In the shade of willow trees, a ten-piece band, Michael Arenella and His Dreamland Orchestra, belted out jazz standards while sequined showgirls performed in the style of the Ziegfeld Follies. Hundreds took the dance floor for the Lindy Hop, while lurid cocktails with names like Strike Up the Band and Flappers Delight flowed. Jay Gatsby would have felt right at home.

In a break between sets, I wandered to the south side of the island to seek out the nature-lover’s version of a retro party: the Billion Oyster Project, which aims to restore the oyster reefs that once encrusted the entire 220,000-acre Hudson estuary. The project grew out of other environmental initiatives, beginning in 2008, of the Urban Assembly New York Harbor School, a unique public high school whose curriculum includes sailing, diving, marine biology and aquaculture. Inside the squat brick school building, the project’s director, Peter Malinowski, the brusque 32-year-old son of an oysterman from Block Island Sound, showed me around a laboratory that Victor Frankenstein might have loved. It was filled with 60-gallon silos connected by plastic pipes and containing oysters in various stages of development. “We ask New York restaurants to give us their used shells,” Malinowski explained, as he fished out a mollusk. The larvae from wild oysters then attach to the soft interiors. “When they have their own shells, we put them into the harbor.” To explain his point, he placed one of the 2-day-old larvae under the microscope, where it squirmed like a baby alien.

So far 16.5 million oysters have been reintroduced to beds from Governors Island to the Bronx River—still a tiny fraction of the billion evoked in the project’s name. “Of course, oysters covered 200,000 acres of estuary in the old days, so it’s just a drop in the bucket,” he confessed. “Maybe we should have called it the Hundred Billion Oyster Project.”

The quality of the New York waters has improved radically in the last decades, Malinowski said, with shad, giant striped bass and sturgeon now being fished (even if the eating quotas are limited to one a month, and none for kids or pregnant women). But there is little chance we will be dining on Williamsburg Blonde oysters in restaurants any time soon. “It’s still illegal to eat New York oysters, and they’ll make you sick,” he sighed. “So long as raw sewage is ever going into the harbor, we can’t have that conversation. If we get a quarter of an inch of rain, the storm drains still overflow.”

**********

The working waterfront really came into its own after 1898, when the various municipalities and the independent city of Brooklyn were joined with Manhattan to form modern New York City. “The purpose of the merger was to unite the harbor facilities under one administration,” explains the official Manhattan borough historian, Michael Miscione. “In fact, if it wasn’t for the port, New York City as we know it would not exist.” The evidence is still there on the city seal, he adds, which includes a Native American and a sailor using a nautical plummet, a weighted line used to measure depth.

The move turned the city into the maritime powerhouse of the 20th century. The image of enormous ocean liners and merchant ships lined up at the Hudson River wharves framed by Midtown skyscrapers astonished the world with its futuristic ambition, inspiring one visitor, the German film director Fritz Lang, to create Metropolis.

To recapture this mythic moment, I went to meet Eric Stiller, whose company Manhattan Kayak lures about 8,000 people every summer onto the river at its more intensely urban point. To reach his office, I walked along 42nd Street, past the neon-spangled Times Square and Broadway theaters, to Pier 64, which lies in the shadow of the gargantuan aircraft-carrier-turned-museum the USS Intrepid. As dusk began to fall and speeding ferries and police craft created unnerving wakes, we paddled south along the Hudson to admire the golden light glinting off the Empire State and Chrysler buildings. From wave-level, it was easy to see why Thomas Wolfe raved in his 1940 essay “The Promise of America” of “our intensest ray, the splintered firmament of the towered island of Manhattan,” or why Truman Capote described the island as “a diamond iceberg” in 1948.

The high-water mark of New York’s maritime industry was the Second World War. But by 1954, when Marlon Brando appeared in On the Waterfront, a great tradition had gone badly awry. Air travel was replacing passenger liners, container shipping was being diverted to New Jersey and waterfront industries were collapsing. The movie was based on a Pulitzer Prize-winning 1948 investigation by reporter Malcolm Johnson, who wrote a sensational exposé of the organized crime and violence of the docks as “a jungle, an outlaw frontier.” Soon, piers and warehouses were abandoned, General Electric was poisoning the Hudson with PCBs and the East River had silted up and become a de facto dump, with rusted cars clustering around the base of the Brooklyn Bridge.

Today, as the current carried our kayaks south, the recent revival of the waterfront unfolded like a cinema montage. The success of the Hudson River Park opened the largest open space in the city after Central Park, and in 2003 an avant-garde Richard Meier apartment building started a land rush to the river, which was soon nicknamed by real estate agents “the Gold Coast.” Cranes now hover over ever more shiny luxury condos, as well as the vast construction site of the Hudson Yards, a 28-acre development over a railroad depot, the largest private real estate project in U.S. history. There seems no end to the creativity. Billionaire entertainment tycoon Barry Diller is funding a fantastical $170 million park on an offshore platform to replace Pier 55, next to the pier where survivors of the Titanic landed in 1912 (they were housed in the nearby Jane Hotel), and plans are afoot to turn the derelict Cunard Line pier into a commercial complex, including America’s largest food court overseen by Anthony Bourdain. On the other side of Manhattan, a $335 million plan was approved last year to landscape the East River Park with sloping earthen walls, or berms, salt-resistant vegetation and pop-up sea walls. Nicknamed “the Dryline,” the renovated park will protect the Lower East Side against the sort of storm flooding that came with Hurricane Sandy and function in good weather as an elegant riverfront recreation space. On a more modest scale, rescued historical ships like the Sherman Zwicker schooner from the Grand Banks fishing fleet in the North Atlantic have been turned into wildly popular restaurant-bars. Still other projects have the ring of science fiction. In 2020, the world’s first self-filtering swimming pool, +POOL, will open in the East River. Funded by Kickstarter campaigns, a three-tier filtration system was developed to remove all traces of bacteria. The prospect has attracted the attention of the many other world cities located on neglected bodies of water, including London, Rome and Bangkok. “New York City is the ultimate testing ground,” said the +POOL director, Archie Lee Coates. Sounding like a Frank Sinatra song, he added, “If we can do it here, we can do it anywhere.”

Since 2007, a nonprofit organization called the Waterfront Alliance has been trying to coordinate the disparate ideas and management efforts, so I joined its officials on their annual City of Water Day celebration. Sailing in the Clipper City, a replica of an 1850s two-masted boat built from plans found in the Smithsonian Institution, we were regaled with optimistic speeches by representatives of the National Park Service, the Coast Guard, a city council member who joins an annual triathlon race in the Hudson and the Army Corps of Engineers, which is repairing the damage from Hurricane Sandy.

“The 21st-century waterfront will need government,” said the Alliance president and CEO, Roland Lewis. “For generations, the guiding force was commerce —unions, shippers, even the mob had a stake in efficiently running the harbor. But now it’s owned and operated by us, the people!” As a result, it has been “Balkanized” into pockets of activity. “We need a holistic plan,” added Lewis. “The water is an unrealized asset that will attract the world to New York. It should be as much a part of the city as in Rio or Hong Kong.”

**********

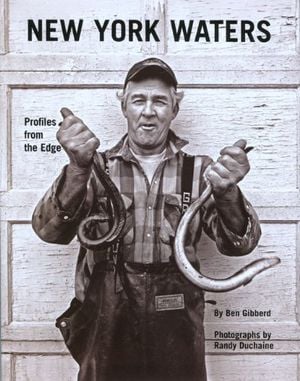

Not everyone is a fan of the brave new waterfront, with its focus on recreation and residential developments rather than gritty industry. “I’m a romantic,” says Ben Gibberd, author of New York Waters: Profiles from the Edge. “I loved the old harbor with its working tugs, its decaying piers and vague sense of ruin. It was just so beautiful. The new version with all its parks is generic and sanitized—a ‘noose of green.’ It’s as if someone had an idea of how a waterfront should look and came up with a cookie-cutter plan for the whole city.” A low ebb, according to Gibberd, was when the last dry dock in Red Hook was paved over in 2008 for the Ikea superstore’s car park. “I don’t want to get sentimental about the bad old days, with its drug dealers and transvestite prostitutes. It’s nice to have an Ikea store by the water. But you can’t replace history. Once it’s gone, it’s gone.”

To find a site where the very idea of the “working waterfront” is being redefined, I took a taxi to the Brooklyn Navy Yard in Greenpoint. Opened in 1801, this was the first naval repair facility in the United States, and it could not have finer maritime credentials: It was here that the USS Monitor was clad with iron plate during the Civil War and the USS Maine built, to be sunk in Havana Harbor. So were the USS Arizona, which went down in Pearl Harbor, and the Missouri, upon whose deck the Japanese surrendered in 1945. “The yards were a huge economic engine for New York City,” said Elliot Matz, the executive vice president and chief operating officer, as we visited a crane on what is now New York City’s only working dry dock. At its height in World War II, over 70,000 people worked on the sprawling, 300-acre site. After its closure in 1966, the city bought the yard, and eventually reopened it as an industrial park. As the headquarters for the North Atlantic fleet during World War II, the yard abounds with stories of new tenants entering warehouses and finding faded sea charts and radios gathering dust.

In the last two decades, the Navy Yard has become a runaway success, with 330 tenants and 7,000 workers now restoring its old energy. The vast majority are no longer in traditional blue-collar trades, but work in electronics, light industry and the arts, including the first film studios built in New York since the silent era. Even more modern “Brooklynesque” elements include a boutique whiskey distillery and a rooftop farm called the Brooklyn Grange, which after the heavy summer rains when I visited was turned into a miniature Venice. The yard is now a unique balance of past and future, with high-tech touches like wind-powered street lights, solar-powered trash compactors and New York’s only LEED Platinum-rated museum, filled with artifacts from the maritime glory days.

Over 40 artists have studios on site, including Pam Talese (daughter of the writer Gay Talese) whose paintings record the eerie historical landscapes of the harbor. (One typical series is called Rust Never Sleeps.) To Talese, the yard is a microcosm of the city itself. “It’s such an amazing confluence of cultures,” she said, dabbing her brush on an image of a floating lighthouse. “You see Hasidic guys, Jamaicans, Italians, dock workers, old sailors coming down here to fish. They’re all just hanging out with boutique bootmakers and the younger IT entrepreneurs, the skateboarding set. This is New York.”

**********

For the time being, it is comforting to know that there is no shortage of forgotten corners in New York’s 520 miles of city coastline, although it helps to sail with obsessive urban explorers like Avram Ludwig to find them. One favorite is Coney Island Creek near Gravesend, now a ship’s cemetery. After anchoring by a muddy bank, we motored in an outboard dinghy past rotting barges and the hulks of wooden vessels, before spotting a surreal vision: a rusted submarine painted bright yellow. Although legend holds that it is a Civil War relic, the Quester I was actually built from salvaged metal by a zealous New York shipyard worker named Jerry Bianco in the 1960s. The sub cruised Coney Island after its launch in 1970, but was ripped from its moorings by a storm and became wedged on the banks here soon after. The yellow color scheme was not an homage to the Beatles, Bianco told reporters, but because he got a deal on yellow paint.

My final summer excursion was to Brooklyn’s Gowanus Canal, which despite heroic cleanup efforts that have brought back fish and crabs, is still green-tinged and reeking, its shores lined with the hulks of forgotten factories. (It was even found in 2015 to have developed a strain of gonorrhea.) After motoring up this toxic artery, Ludwig suggested we land on a derelict stretch of industrial Williamsburg. Reaching dry land involved clambering through a wire fence, walking a narrow rusted pylon like a tightrope above debris-filled water, then levering around a knife-edge of crumbling concrete while clinging on to broken pipes.

This Mad Max adventure went awry when I ventured onto algae-covered rocks by the shoreline to help tie up the dinghy. Catching the mooring rope, I lost my balance, the rocks slippery as ice. The next thing I knew, I was bobbing upside down in the East River.

This was a new relationship to the urban environment for me, to say the least. For some reason, my mind drifted back hopefully to my conversation with Deborah Marton, director of the New York Restoration Project. “The waterfront has a health and psychic value to New Yorkers,” she had assured me. “It also has a spiritual value. It tells us we are on the earth. We’re part of a larger system.”

After I crawled out with only minor abrasions, Ludwig looked me up and down approvingly. “That’s your East River baptism,” he said. “But maybe go have a shower.”

New York Waters: Profiles from the Edge

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)