New Photo Book Explores Places the Dead Don’t Rest

From mossy burial caves to bone-filled churches, photographer Paul Koudounaris spent a dozen years documenting sites where the living and dead interact

Americans, despite their religious and cultural differences, seemingly have a rather uniform way of treating the dead: making them more or less invisible. After a brief funeral, the recently deceased are stuffed six feet deep, scattered to the wind, stored in a crematorium niche or relegated to the mantelpiece alongside dusty photographs. But in a new book, photographer Paul Koudounaris aims his lens at cultures where the dead play key roles in the lives of the living—as in a Bolivian festival where skulls are strewn with flower petals, or on Indonesian islands where the mummies of deceased family members are kept at home and given a place at the table, both literally and figuratively.

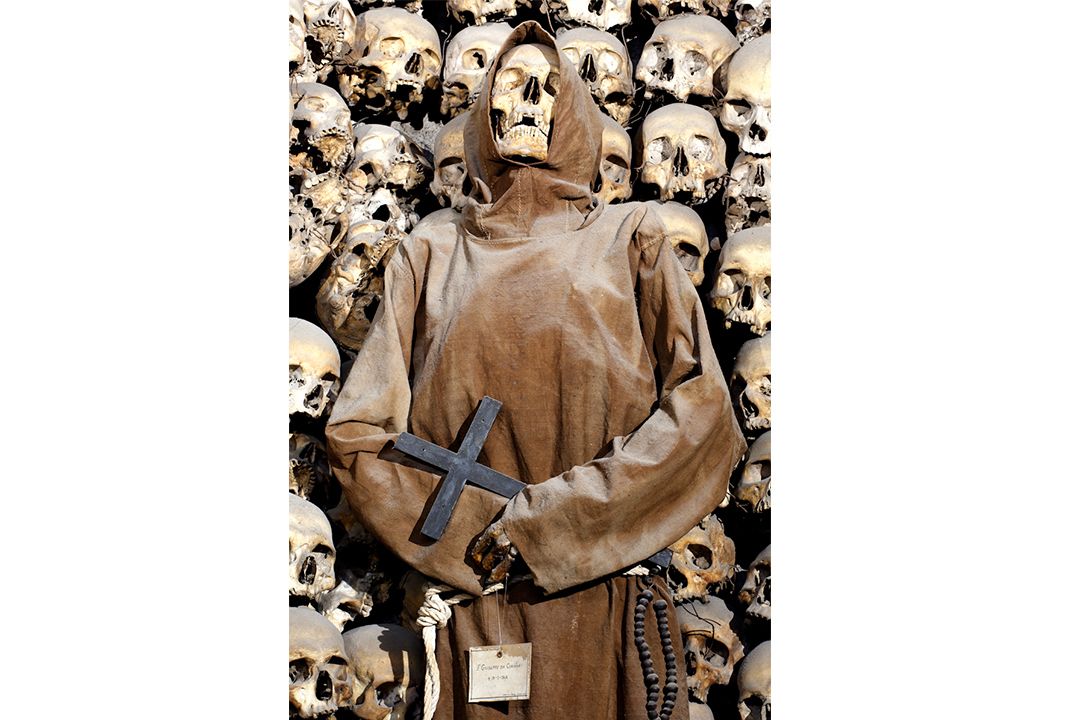

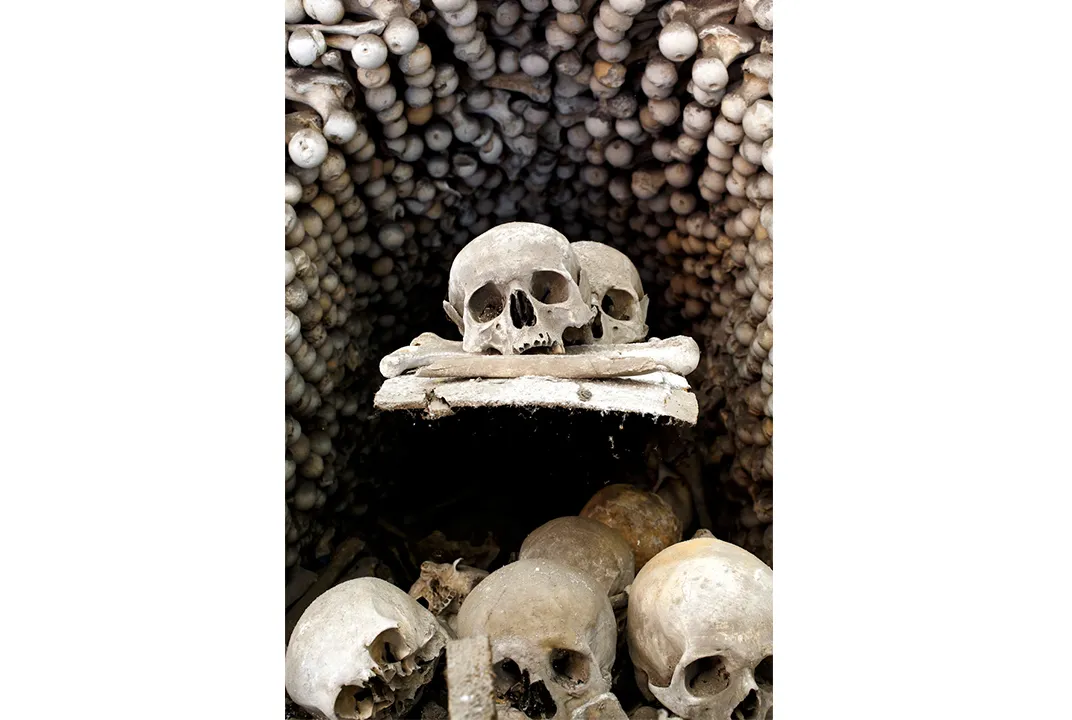

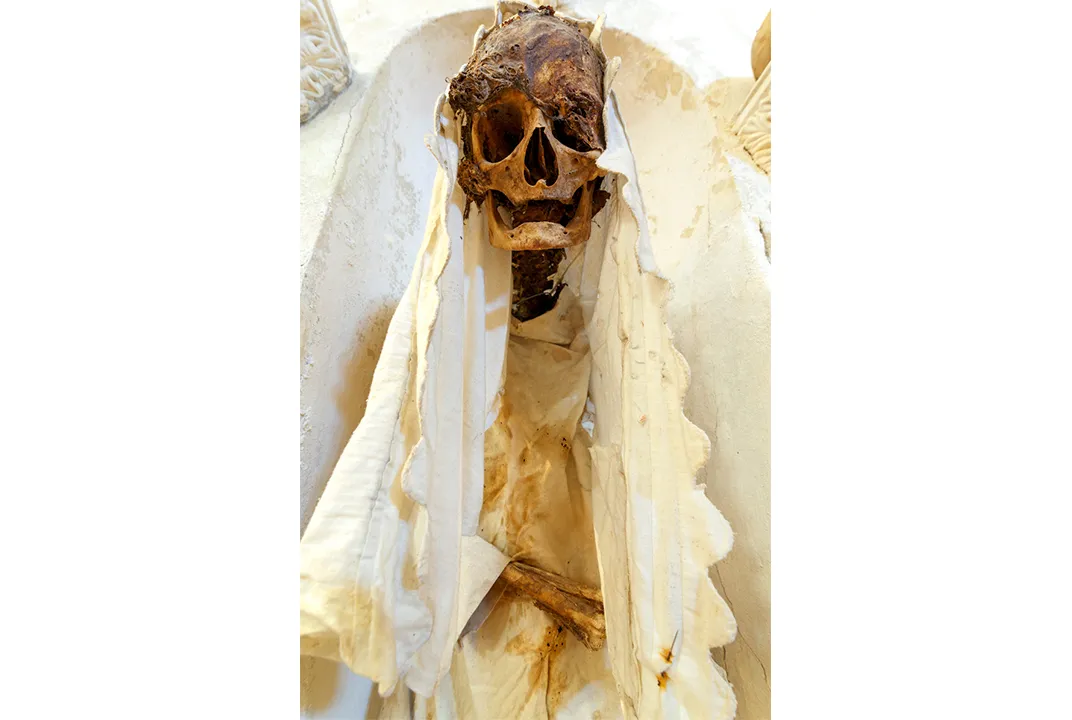

Koudounaris also visits places in Europe where the dead take center stage, such as the bone-filled charnel houses of the Paris catacombs or the lovingly preserved mummies of the Capuchin crypts in Southern Italy. The result, collected between the sky-blue covers of Memento Mori: The Dead Among Us, is a tour through 250 sites in 30 countries where human remains are used to enrich the lives of the living—whether to spur spiritual reflection, maintain family bonds or simply to create incredible works of art.

Dubbed “Indiana Bones” by the British press, Koudounaris refers to himself, jokingly, as the Fox Mulder of art history. He’s made a career out of traveling the world to take photographs of human remains, creating images that manage to be both beautiful and unflinching. His first book, The Empire of Death, was an in-depth history of charnel houses and ossuaries in Europe, while his second, Heavenly Bodies, surveyed the bejeweled “catacomb saints” of Western Europe. As Koudounaris explains it, these anonymous skeletons were plucked from the catacombs of Rome in the 16th and 17th centuries, encrusted with gems and metals by Catholic nuns in German-speaking Europe, and more recently locked away in closets and cellars as the Church modernized.

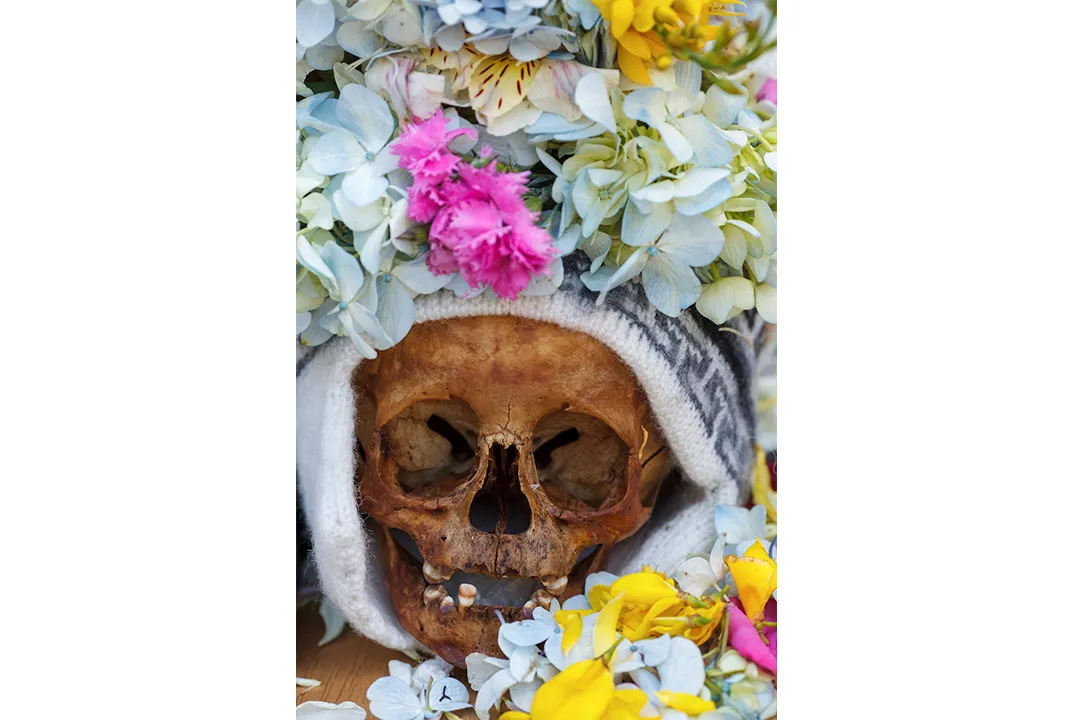

Memento Mori takes a more global view than the previous books, prompted in part by a celebration that might seem strange to Western eyes—the Fiesta de las Ñatitas in Bolivia. There, Koudounaris writes, people from all walks of life “own skulls known as ñatitas (a nickname roughly meaning the ‘little pug-nosed ones’), which are enshrined within the home and considered esteemed friends or family members. Ñatitas may provide any number of services, as guardians of the domicile, trusted advisors, spiritual guides, or simply good-luck charms.” The practice stems, according to Koudounaris, from the belief among the Aymara Indians of the Bolivian highlands that death is not the end, but merely a transition to another phrase of life. The skulls aren’t from dead family members, but anonymous specimens taken from graveyards and archeological sites (even the homicide division of the national law enforcement agency has a pair). On the Fiesta de las Ñatitas, held every November 8, the skulls are removed from their homes and taken to local cemeteries for a celebration in their honor, where they are serenaded by musicians, strewn with flower petals and given offerings of candy, cigarettes and booze. Sunglasses protect their eye sockets and woolen caps their heads; they are, after all, only taken out one day a year, and their human caretakers try to make them feel comfortable.

Koudounaris recently spoke to Smithsonian.com about his new book, the years he’s spent photographing bone churches, burial caves and bedazzled skeletons, and his ideas about life, death and tourism:

What got you into photographing the dead?

Like everything in my life, it happened by accident. I had finished grad school in art history, and I was doing what people normally do after grad school, which is try to find any way to avoid having a job. I was traveling around aimlessly in Central Europe, and I had gone down the wrong doorway in a church in a small Czech town and discovered their charnel house, which was fabulous but completely unknown, even to people in the city. And it sparked this line of inquiry—how many other places like this are still around that no one knows about?

After I started researching, I realized there were hundreds of these sites at one point in time. It was an important element of spiritual life, at one time, to confront the dead, and these sites had all kind of gotten swept under the rug just because we as a society have this anxiety about confronting the dead. It’s now the don’t-ask-don’t-tell of visual culture. I wanted to not just understand these places, but to get recognition for them as works of art.

How did you get from ossuaries to jeweled skeletons to all of these sites?

During the research on the charnel houses in Germany, it was inevitable I’d come in contact with the jeweled skeletons, and being who I am, that I’d fall passionately in love with them. Not only are they beautiful, it’s also a tragic story of these anonymous people who were raised up to the holiest of the holies, only to be cast down again. But the entire time [I was working on the other two books], I’ve also been sneaking off to other places around the world.

At one point, I wanted to do something just about the skulls in Bolivia. But there was no market for that, because there’s no market for the cultural output of Bolivia. To be honest, Memento Mori has a lot to do with those skulls, because the only way I could get them recognition in a fine art-type book was to roll everything together. Everything from around the world—Asian stuff, South American stuff, the best of the European stuff, etc. Really, the book came about because of the desire to get those Bolivian skulls their due in print.

What are the most famous places in the book, and which are your personal favorites?

The biggest one, physically, and also the most famous, is the Paris catacombs. And if you want, you can call it the best—certainly it has the most bang for its buck because they’ve got the got most people down there. Santa Maria della Concezione in Rome is also extremely famous, as is the Sedlec ossuary, and the Chapel of Bones in Evora, Portugal. Those are the big four.

It’s hard when people ask which sites are my favorite. They’re kind of like my children. But I love the crypt of mummies in the Capuchin crypt in Burgio, Sicily. It receives almost no visitors, no one knows about it. It hasn’t been tampered with, and it has this air of authenticity to it.

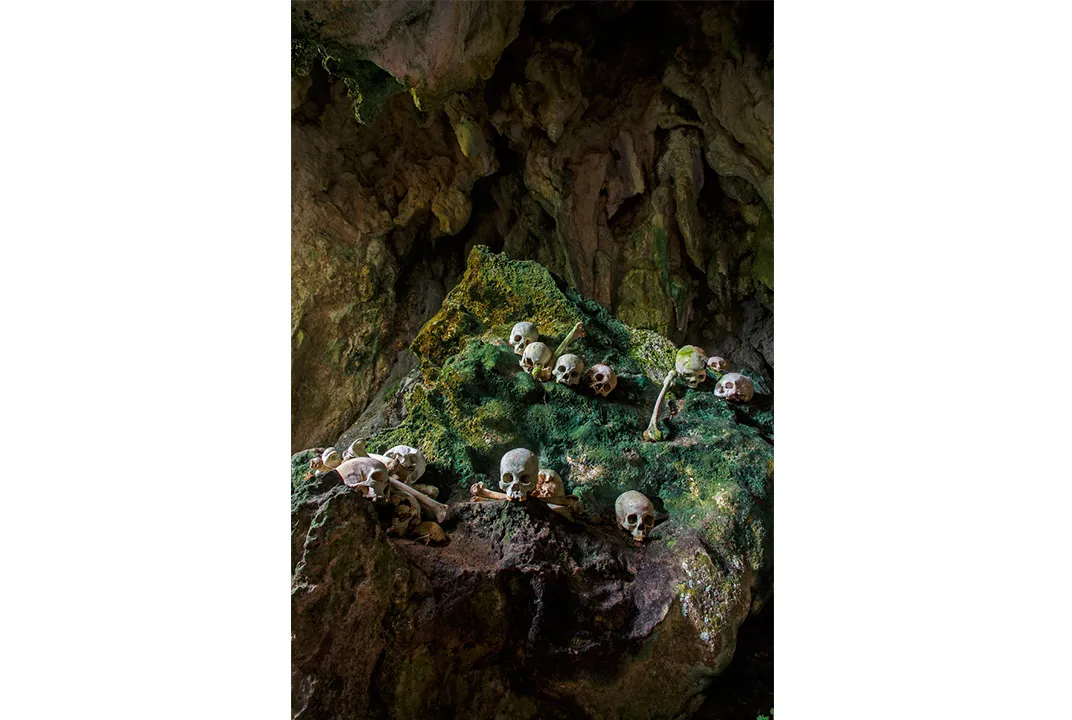

But if I really have the pick a favorite, one that would include the whole experience of getting there and being there, it’s the burial cave of Yemrehanna Kristos in Ethiopia. That place is extremely remote, it has this incredible history, it’s been around for a thousand years. You have to hire someone with a four-wheel drive that’s sucking up dust, people are running after the car screaming at you because nobody comes that way, and then you have to get there, climb up a mountain, and explain what you’re doing to the priest.

That my next question—how were you able to get access to these sites? In some cases, these places have never been photographed before.

I get this question all the time, and sometimes I really don’t know why I’m given access. All I’m armed with is the idea that I have good intentions. A lot of the people [I encounter] are very sheepish about museums and anthropologists because they’re afraid they’re going to steal their treasures, so maybe it’s because I come across the other way—a solo guy, who’s not institutional, and I’ve made the dedication to come all this way. … And there’s a reverse kind of mechanism that happens when you go from Los Angeles, in particular, to another culture, and you want to know about their thing. Sometimes they’re dumbfounded. We’re such cultural exporters, but I want to go the other way.

When a Westerner looks at these sites, they often look so sinister. They remind us of horror movies. But you’ve said that in many cases they’re created as an act of love. What are some specific places that are examples of that?

The sites where that is most prominent in the West is with those mummies in Sicily and Southern Italy, like in Burgio. They are the best example of that continued bond, where the dead are still treated a beloved family member. But there are other places like that too—the painted skulls in Halstatt, in Austria, for instance, and skulls like that used be all over Germany, Switzerland and the Alps. … [They allow] you to continue that relationship with a specific individual after death by identifying them.

And there are places like this in other cultures. In the burial caves in Indonesia, the skulls themselves are anonymous, but often they have statues, or effigies, or tau taus, as they call them, which are supposed to be the embodiment of the people, a kind of soul house for them. It serves a similar function of allowing that kinship bond with the specific person to be preserved after death—and it’s preserved out of love.

Why do you think many of these sites seem so shocking to us now?

Because we have this incredibly anxiety about death, and we feel we needed as a society at one point to sweep it away. There are several reasons for this—hygienic changes, ideas about where the dead should and should not go. But it also goes back to Descartes, and this idea that if something isn’t thinking, it doesn’t exist. And this is something I kind of borrowed from [French philosopher Jean] Baudrillard, but I think that capitalism has a lot to do with it. We are so future-oriented, so progress-oriented, that we had to cut the dead out as a kind of anchor to the past, because, well, nothing makes you as contemplative as being around a bunch of dead people. We have a social economy that is very fast-paced, and the dead don’t really fit into that, except to try to commodify them.

Do you think there’s any chance that Americans will move to a place where there’s less anxiety about death, and we might have more interaction with dead, as in the places you photographed?

The pendulum is swinging back. I think it’s swinging back very slowly, and I have no idea how far it will go, but it’s finally starting to swing back [in this country]. People are conscious enough of the shift that they invented their own term for it: “death positive.” I think a lot of it has to do with immigrant culture, because the United States has absorbed so many immigrants—people from South America, from Latin America, from Asia and elsewhere—that never attached the stigma to the dead that we have. The immigrant culture in our society has forced a bit of reorientation.

You have to understand, there’s the dead, and then there’s death. The dead are pretty much universally the same thing—not living. But death is a very a culturally relative boundary, and a culturally relative term. Some people really struggle with this. But “death” is the boundary between two groups, and it can be placed in different places. The terms I’ve been using are the soft boundary and the hard border, and usually it’s one or the other. Societies tend to structure their relationship with the dead according to one of two poles—either trying to cross that gap [between the living and the dead] is a form of cultural taboo that’s frowned upon, as it is in American culture, or it’s a soft boundary that’s very permeable and allows a dialogue, a reciprocal relationship that goes on across that boundary.

And what you find is that our way is really very historically eccentric. You can go back to prehistoric times and find skulls that have been decorated, which are evidence of that kind of soft boundary …. Once history becomes documented, even when human remains aren’t fetishized, the soft boundary is still in play. You have things like the Roman festival of Parentalia, where you made contact, you opened that portal back up, the living and the dead did interact. A good Roman was expected to keep those ancestor busts, and to have that meal with them, inviting them back in to carry on that kinship relationship, even if only symbolically. So our way is not normal … and I don’t think it’s healthy.

Do you think it has anything to do with Western luxury, that we can afford to keep the dead away?

I don’t think it’s about luxury, I think it’s about necessity. We needed to keep the dead away. But sure, we’re not in a point where people are dying in the street, and we are forced to confront it…. But I do believe that people live healthier and better-adjusted lives when they are confronted with mortality. It doesn’t take the sting or pain out of dying, but it acculturates us to see this as a natural process, as something is normal.

In this culture, we treat death as a failing, of the doctor, or the body to sustain itself. Our rituals support that: we make them up and position them in the coffin to make them look like they’re just sleeping. In Sicily, when they make up the mummies, they’re not pretending they’re still alive, they’re treating them as dead people, because there’s no stigma about being a stiff. You can be a stiff and still be a member of society.

Do you see this book as fitting into the idea of dark tourism—people intentionally visiting graveyards, genocide memorials, etc., on vacation? And what do you think of that phenomenon in general?

That’s a source of much anxiety in my life. I respect these places as sacred sites, and I don’t like the way they are cheapened, especially once they become tourist sites, and I have to be aware that my own work may hasten that process in some cases. … It’s one of the things I try to be sensitive about in my book—I want it to have the respect due to a sacred item or a sacred site.

It’s hard for me, because I know that in the process of doing what I love—finding these places and photographing them—I am in a sense betraying them. I’m putting them out there so they can be ripped off and become memes. It’s not the only potential outcome, but it’s something I grapple with.

But I also think there’s a social prejudice and misunderstanding, that people who are into the macabre are a bunch of yahoos in Danzig belt buckles. And there’s a misunderstanding about dark tourism. But people who are seeking this stuff out are the most likely, other than ecclesiastics, to understand it and to appreciate its sacred context, because they care about it and it’s a lifestyle choice for them, it’s meaningful to them. If any good comes out of what I do, in terms of people visiting these places and that potentially providing money for restoration, it’ll be through people who are into stuff like dark tourism.