India’s Holiest City

At Varanasi, Hindu pilgrims come to pray—and to die—along the sacred Ganges River

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/varanasi_monk_388.jpg)

He has come for his final pilgrimage. Dressed in white, with his gaze hollow and cheeks gaunt, the man is helped off the plane and into the Varanasi airport's one-room terminal. Travelers elbow their way to the front of the baggage belt, but he and his loved ones are calm, untouched by the confusion around them. Fellow passengers lower their eyes in respect as his relatives push his wheelchair out of the airport and into the hot sun. It is his time. He has arrived in India's holiest city to die.

Located more than 400 miles southeast of New Delhi in Uttar Pradesh state, Varanasi, also known as Banares or Kashi, is one of the world's oldest living cities. It is a place respected by Buddhists, who believe Buddha delivered his first sermon nearby after his enlightenment, and revered by Hindus, who come by the millions every year, across oceans and from all corners of India, to show their devotion.

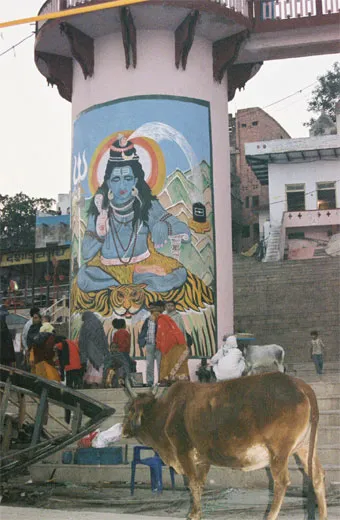

Varanasi is steeped in myths and legends. Hindus believe that Shiva, the god of destruction and re-creation, and his wife Parvati have made their home here since the beginning of time. Shiva is said to have also blessed the city with Ganga Ma, Mother Ganges, at one time a river in heaven. The great Shiva let it cascade to Earth through his matted locks of hair. For thousands of years, Hindu pilgrims have lived their lives hoping to bathe here in the spiritual waters and embrace death, believing that if they die in Varanasi and their ashes are scattered into the river, the act will end their cycle of reincarnation and they will go to heaven.

The heart of the city lies along more than 80 ghats, or sets of stairs, that descend into the western side of the Ganges river. Along this more than four-mile stretch, activities range from the mundane to the religious. Local men and women swim and bathe. They wash their belongings and put them out to dry on the river's bank. At dawn, hundreds of devotees immerse themselves in the Ganges, and, with arms stretched to the sky and water slipping from their cupped hands, they cleanse away sin. At dusk, while bells ring, tambourines jingle and taped Hindu prayers blast over loud speakers, holy men perform rituals in front of crowds of followers and handfuls of Western tourists.

Back from the river, the tops of Hindu temples and Muslim mosques dot the skyline. A narrow maze of streets reveals shops the size of closets, vendors hocking food and yards of Varanasi's signature silk, paint-chipped apartment buildings and cheap hostels and, around a few corners, unexpected treasures—a bright orange, human-sized Ganesh statue or an intricately-designed turquoise door. On main roads, dusty cars, rickety cycle rickshaws and stubborn cows jostle for room. Women in fuchsia saris beg passersby to buy marigolds as prayer offerings. And scholars join the throngs at the nearby Banaras Hindu University, the largest residential university in Asia.

Life meets death at the Manikarnika ghat, the main cremation area in Varanasi. Nearly all day and night, red- and yellow-swathed bodies burn on wood funeral pyres. India’s lowest caste, the Untouchables, stoke the fires, as relatives and friends observe their loved ones turn to ash, which is later scattered in the Ganges, a joyous, yet solemn process that means salvation for the dead. The city is such an auspicious place to die that many come to live their last days in a hospice near the ghat. Those who cannot afford the nearly U.S.$100 cost of cremation—a fortune to many Indians—fashion their own death rites, praying while throwing their family member's entire body into the Ganges.

Plagued by years of overuse and raw sewage, the river is not immune to problems. The water in Varanasi registers a fecal coliform rate that is 3,000 times higher than deemed safe—a problem that local groups such as the Sankat Mochan Foundation and their Clean Ganges Campaign have been fighting to reverse through a community awareness campaign. Nonetheless, over the last several weeks, some 70 million people have gathered to bathe in the Ganges in nearby Allahabad for the Ardh Kumbh Mela festival, the largest religious gathering in the world. For most Hindus, the Ganges "has transformative power. It cannot be threatened by anything or anyone," says William Alle, professor of religion in India at Temple University. "She is a goddess." A goddess that is brought to life daily in Varanasi.

An amalgam of contradiction, the city is chaotic yet serene, dirty yet pure, aged yet ageless. There is a sense that it has not changed in hundreds of years and will not for hundreds more. It is India's holy city, a city of light and death, a city that gives its pilgrims salvation.