In Texas, a Locavore’s Liquor

Microdistillers are making their mark around the Lone Star State

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Distilleries-St-George-Spirits-631.jpg)

For most of the past century, any spirit produced in Texas was moonshine, much of it low-quality hooch mixed for bootlegging. After Prohibition, it was legal to distill — once you obtained requisite permits — but few ever bothered to register their operation with the government. “The people in Texas come from a line of frontier marchers. They’re kind of like, ‘Who are you to tell me what to do?’ says Bert “Tito” Beveridge.

Beveridge, a square-faced fortysomething with a quick grin, is recounting his early moments in the liquor business: making habanero-infused vodka for friends, quitting his day job and finally licensing his distillery in the mid-1990s.

A fifth-generation Texan, Beveridge was no moonshiner; he wanted to start a business. In 1995, when he set about navigating the state and federal permitting process, there were just a handful of microdistilleries around the country (the first, California’s St. George Spirits, was founded in 1982). So Beveridge tangled with state and federal licensing authorities alone.

The state authorities were the most difficult hurdle: Texas has been producing beer since Germans brought their brewing traditions to the state in the 1840s, but until recently, legal liquor distilleries were was all but unheard of.

“When I found out there’d never been a legal distillery in Texas, I was surprised,” says Beveridge, leaning back in a swivel chair. We’re sitting in a small, sunlit office at his 25-acre distillery south of Austin, where, since 1997, the former oil geologist has been producing Tito’s Vodka — Texas’ first legally distilled spirit since before Prohibition, which ended in 1933.

“When [Tito] went to get permission [from the state], there was no procedure in place to get a license,” says David Alan, an Austin-based mixologist and writer. “He really cleared a path in the jungle.”

Bottles of Tito’s Handmade Texas Vodka (he has since dropped “Texas”) first hit stores in 1997; he sold nearly 1,000 cases that year. Today, however, he may no longer qualify as “micro.” With a bottling plant the size of two hockey rinks, over 300,000 cases distributed across the United States and Canada and some international awards to his name, Beveridge is poised to challenge some of the world’s bigger liquor producers.

This has left an opening for newcomers to make their mark in Texas. Today nearly 20 independent, small-scale distilleries are producing liquor in Texas. Their offerings run the gamut, from award-winning vodka to more unique tipples like limoncello and Texas bourbon.

Some of these micro-distilleries are simply seeking a piece of the $60 billion alcoholic beverage industry dominated by multinational conglomerates such as Brown-Forman and Diageo.

Others are following a road paved by the micro-brewing movement, carefully crafting small batches of complex spirits using high-quality local ingredients. “This is all part of a renaissance in our society where we’re making wine, bread, beer and cheeses,” says Bill Owens, president of the American Distilling Institute.

This phenomenon has not developed in isolation – if anything, Texas is lagging behind a national trend. From California to New York, microdistilleries are popping up — the number in the United States has grown in the past decade, from a few dozen to over 200. Still, the Lone Star State is important to the industry, not only for its considerable potential as a place of future development, but also as the origin of this nascent movement’s true success stories.

Waco, home to many Baptists who frown upon alcohol consumption, is one of the last places in Texas you would expect to find a distillery.

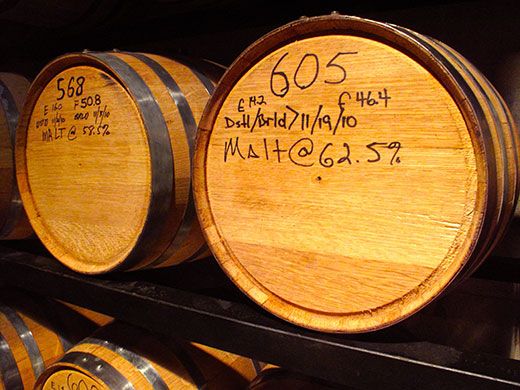

But inside a 2,000-square-foot building in the city’s warehouse district, lies Balcones Distillery, all shiny copper stills, exposed ceiling beams and steel vats brimming with fermented fruit and grain. A handful of young men mill about, pounding plugs into small oak barrels and sampling snifters of golden-colored whiskey.

Chip Tate, the full-bearded owner of Balcones, opened the place in 2008 after a stint as a Baylor University administrator. “For me, this all started as baking when I was 11,” he says. Tate, who, as a grown–up, has dabbled in cheese-making and professional brewing, constantly draws on his appreciation for food to get ideas.

A couple of years ago, he had hopes of making a liquor that used 100 percent Texan ingredients. At home, he had just made a dessert sauce from Texas figs, honey and sugar. In the distillery, he fermented the same ingredients and the final product became Rumble, a spirit that’s now part of Balcones’ regular offerings. In addition to its success in last December’s “Drink Local” cocktail contest in Austin, it won a silver medal at the San Francisco World Spirits Competition last spring.

Tate places an emphasis on quality regional ingredients: another of his spirits, Balcones’ Baby Blue corn whiskey, is made from New Mexican Hopi blue corn.

But the epitome of locavore liquor may be the bourbon made at Garrison Brothers’ Distillery, located in bucolic Texas Hill Country, an hour west of Austin. (Contrary to popular belief, bourbon whiskey does not have to be made in Kentucky. Among the requirements codified in federal law is that bourbon has to be distilled in the United States, be made from at least 51 percent corn and be aged in a charred new oak cask.)

On rolling ranch land near President Lyndon B. Johnson’s hometown, owner Dan Garrison grows organic wheat and collects rainwater for cutting down the proof of his bourbon before bottling. His spent mash, previously distilled fermented grain, is used by local farmers for animal feed.

“Everyone around here takes good care of the land,” Garrison told me during a distillery visit recently. “We try to be good stewards as well.”

These efforts to be inventive or local — or both — have not gone unnoticed. Last October, Garrison released about 1,800 bottles of his first two-year aged bourbon in Hill Country liquor stores. By early December, it was almost sold out.

“A whole segment of our society is getting more adventurous,” says David Alan. “The palate is expanding.”

Yet it is vodka — easy to drink and mix — that dominates the Texas liquor industry. The state is awash with it; including Tito’s, there are at least ten different Texas vodkas, two of which, in a nod to Southern tastes, are blended with sweet tea. This deluge has occurred in part because Texans, like all Americans, have a taste for vodka. Last year, 30 percent of total liquor sold in the United States was vodka, according to the U.S. Distilled Spirits Council.

It’s a profitable venture for distillers because the spirit can be made in a relatively short period of time without a lot of fuss. Unlike whiskey, most of which requires aging, vodka is taken from the still, cut with water and bottled the same day.

“Whiskey is hard to do on its own, because if you’re going to open a business and not make a dime for six years, that’s tough,” says Alan. “If you started a vodka company today, it could be on the [liquor store] shelf within a year.”

American vodka, as defined by U.S. law, must be a neutral spirit: colorless, odorless and mostly tasteless. Most of the grain characteristics are removed in the distilling process; by the time vodka hits the bottle, most of its flavor comes from the water used to cut the proof.

Thus, the grain quality — and source — matters much less than in other liquors; as a result, some Texas vodka producers distill from pre-distilled corn-based spirits bought out of the state.

This is a source of consternation for those like Balcones’ Chip Tate, who see themselves as artisans first, entrepreneurs second. “Distilling is like starting with the best-quality paints on your palette, the majority of which will not end up on your canvas,” he says.

In other words, you have to use a variety of top-notch ingredients and select only the ones that really lend a spirit the best notes. “If you’re not doing that, you’re not really painting.”

But he’s also a pragmatist. With Tito’s popularity across North America, Tate told me that he’s grateful for any spirit produced in Texas, clear or brown, that helps business.

“Craft vodka sells, so we owe them for that. People like Tito are the reason we can get a contract with a big-time distributor,” Tate says.

In 1995, around the same time Tito Beveridge was launching his distilling career, a group of Texas wineries formed the state’s Wine and Grape Growers Association. For 15 years, they’ve organized festivals, advocated for and generally created buzz about Texas wine around the country.

Recently, there have been efforts to start a similar group for Texas liquor producers. Some, like David Alan, think that having more cohesion in the ranks would strengthen the movement and aid attempts to repeal Prohibition-era dry laws in the state. As of November 2010, it was still illegal to sell alcohol in at least portions of 210 of the state’s 254 counties, according to the Texas Alcohol Beverage Commission.

So far, the efforts haven’t taken. “We’ve gotten together and talked, but . . . I’m doing my own thing,” Beveridge says. “I guess I’m pretty competitive.”

For now, camaraderie comes from having “Distilled in Texas” on bottle labels. That alone is starting to turn some heads around the world — last fall, Chip Tate got a call from someone in Sweden who had read about his business and wanted to buy some liquor.

“I think it’s partially that we’re doing unique things, but there’s definitely the Texas phenomenon,” he says. “But novelty will only get a first purchase — you have to make something that’s good.”