The Secret Meaning of Food in Art

Discover 17th-century drinking games and coded political messages in this unique food tour of the Metropolitan Museum’s art collection

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ee/1a/ee1a76e2-0531-46d4-bdac-3a4f915856d0/hb_3162.jpg)

Although snacking in the galleries is still off-limits, visitors can now have a full-course meal in every room of the Met. A meal made of art, to be more accurate.

Angelis Nannos, a worldly, full-of-verve food expert, is leading culinary romps through the museum. At the start of his whimsically-named Yum Yum MET tour, he hands out menus with a flourish: a hint of the items he’ll be explaining that day. But the drinks, the amuse bouche, the appetizers, the pasta course, the entree, and dessert are all, well, art. And while food is the thread tying everything together, Nannos shows off how various objects connect comestible history with larger themes like gender, religion, class, and even old-school political mudslinging. A culinary curator from Greece who’s led food-and-culture tours in Istanbul and New York, Nannos has a way of surprising participants with a combination of modern and ancient, funny and solemn. His sweeping gestures and festive laugh make him, as The Rough Guide to Istanbul puts it, a “wacky but inimitable” guide, and his easy, friendly charm lets visitors happily absorb his knowledge.

“[I] want to show the eternal significance of the food in people’s lives,” Nannos tells Smithsonian.com. Throughout the two-hour journey, which spans centuries of art history, he teaches his guests about 17th-century drinking games, ancient Mesopotamian rituals and the New York City oyster craze, among other delights—all while sliding small treats and trinkets, such as Easter eggs and plastic-pickle pins, into tourgoers’ hands.

“I hope I plant a seed in my guests' minds to start detecting the infinite ways food is interwoven with most aspects of our lives,” says Nannos. Here’s a sample of the menu one can experience on his tour:

Diana and the Stag

Drinks, anyone? This gilded mechanical toy, circa 1620, depicts the god Diana atop a deer—but there's a hidden drinking vessel inside. As Nannos, who excels at bringing older art to life, puts it, the toy was basically an ornate way for 17th-century teens to get wasted. “When used in drinking games,” the Met website explains, “a mechanism in the base was wound up and the automaton was allowed to run freely on concealed wheels until it came to a halt before one of the participants at the table, who had to drink everything in the cup.” Click the video above to see it in action.

Tables for Ladies

This Edward Hopper painting from 1930 gets at several Depression-era issues: money, hunger, gender, class. The scene shows just two patrons eating, perhaps hinting at the fact that during the Depression “many Americans could not afford to dine out.” It also depicts a cashier and a waitress, both women in new roles outside the home. The painting’s title refers to a social innovation at the time: dining establishments that promoted "tables for ladies.” That advertising—aimed at female customers with money to spend—was significant in an era when gender inequality was even worse than it is today. It documents a moment of transition away from a time when a woman alone at a restaurant or bar was assumed to be a sex worker in search of business.

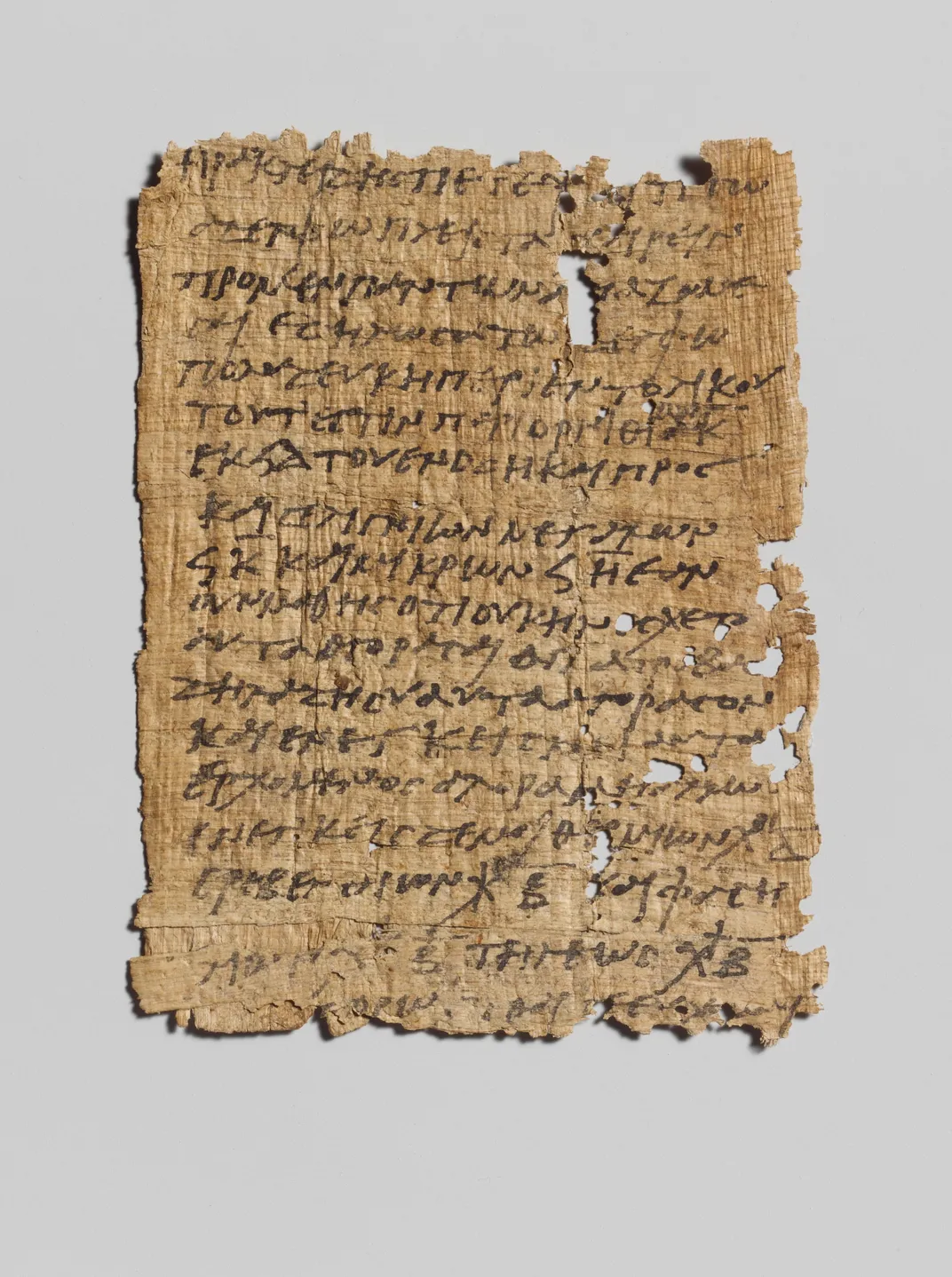

Greek Papyrus

“Wandering around the mezzanine of the Greek & Roman gallery I spotted the tiny papyrus, which intrigued me for a reason,” Nannos says. “Researching its origins, [I] discovered that it’s one of the most ancient shopping lists [to have] survived!” Indeed, this rough piece of ancient paper with indecipherable words scrawled on it, once translated, begins with greetings and kisses from a man to his brother, then asks him to shop for a number of ingredients, including chickpeas, kidney beans, and fenugreek leaves. It’s like when we leave a note for a friend or partner to pick up certain items at the farmers market, Nannos explains. Ancient humans: they're just like us!

Oyster Plate

It may look like just a pretty little dish, Nannos says, but this plate, made by Union Porcelain Works in 1881, tells us about what was once New York’s hottest food trend. The well-crafted object would have been used by the wealthier set to serve oysters at a time when the bivalve was all the rage. Indeed, Nannos says, while the now-museumized oyster plate conveys one aspect of New York’s oyster craze, the mollusk was often served as a casual, cheap, street food that dotted the city the way hotdogs and pretzels do today. They were “consumed, on the half shell or in fragrant stews, at street stands, market stalls and restaurants,” writes The New York Times’ William Grimes. Oyster eaters enjoyed a kind of glory period from about 1820 to 1910, relishing in a food that both rich and poor could afford to eat.

Broken Eggs

“What do the eggs mean?” Nannos asks the group. After several guesses, he explains: The broken eggs represent the loss of the girl’s virginity. Painted in 1756 by Jean-Baptiste Greuze, the scene also includes a younger man and an older woman who's looking none too pleased, as well as a small child. “It is evident from the pout of the girl—as well as from the scowling child who is holding an eggshell and a dripping yolk and who provides the subtext—that something more than eggs has been broken,” the Met writes, going on to explain that “it was the girl’s virtue the youth had violated.” The language the Met uses there seems to take away the girl’s agency. Either way, says Nannos, the girl doesn’t look too thrilled.

Cider Making

When Nannos asks visitors to describe this work of art, visitors usually respond that it’s just some bucolic scene. But the painting turns out to mean much more than that. William Sidney Mount painted it in the early 1840s as a form of political propaganda—the back-in-the-day version of today's door hangers or robocalls. Centered on the 1840 presidential election, the Met explains, “The work was commissioned by the prominent New York businessman and Whig leader Charles Augustus Davis.” The Whig candidate in the race, William Henry Harrison, was “promoted as a common man who preferred a log cabin and hard cider to the supposed excesses of the Democratic White House of Martin Van Buren.” It’s a reminder, Nannos says, that politicians have painted each other as greedy for centuries.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/michele-lent-hirsch.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/michele-lent-hirsch.jpg)