Drawn from Prehistory

Deep within Mexico’s Baja peninsula, nomadic painters left behind the largest trove of ancient art in the Americas

The figures are everywhere. Some are stabbed with arrows and spears. Others seem to stand, horror-struck, arms jabbing straight out from their sides, or raised (bent at the elbows, hands open) in a “don’t shoot” gesture of supplication. Several of them tower like giants, measuring perhaps ten feet from head to toe.

Each of these images, nearly 80 in all, exists as an urgently vivid painting on the ceiling of a shallow cave 150 feet up a cliff face inside Mexico’s deepest outback. Some are rendered in black, others in red; a few are bisected vertically into halves of each color. Many lie at 90-degree angles to their neighbors, arms and legs overlapping. Still others tilt alone into space, as if accommodating their compatriots, obligingly sharing the cave’s ceiling.

This place is San Borjitas. It is but one of an estimated 600 sites in the mountains in the central part of Mexico’s Baja California peninsula, which extends 700 miles south of the U.S. border. The Great Mural paintings, as they are collectively known, constitute the most extraordinary collection of prehistoric art in the Americas. Yet because of their remoteness, the works—perhaps 3,600 years old—remained virtually undiscovered and un-documented until the mid-1970s. Only in the past decade have tourists begun to penetrate this isolated backcountry, in search of paintings to rival those of France’s Lascaux cave or Spain’s Altamira.

First described in the 1770s, when Spanish missionaries to the region told of the “well-preserved” paintings they had found there, the prehistoric masterpieces largely eluded recognition for another two centuries. Popularizing the caves required the 31-year campaign of a selftaught archaeologist, Harry W. Crosby, who pushed through the forbidding mountain terrain to discover nearly 200 of the works himself.

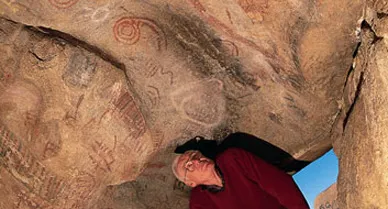

On the afternoon I first glimpse these paintings, Crosby is my guide. Still rangy and fit at 75, he points out several large, flat stones on the gravel floor. “These are metates, or primitive mortars,” he explains, “worn to concavity because ancient artists used these surfaces for grinding colored volcanic rock into pigments.”

Outside the mouth of the cave, hummingbirds zizz past, feeding on nectar from yellow-blossoming plants that fringe this sun-scoured cliff. Tall, cigar-shaped cardon and ocotillo cacti stand outside the cave entrance, their afternoon shadows tracing slowly across the stony ground like sundial tracks. Inside, Crosby contemplates the mural, dense with its highly charged images of beauty and violence. He is peering into a mysterious chapter of North America’s past, working at a task that has absorbed him since he stumbled across his first cave painting in 1967: piecing the puzzle together.

At a time when archaeology has become big business—and fewer scientists can mount heavily bankrolled expeditions that make, document or publicize new discoveries—the saga of Harry Crosby, a dedicated amateur who worked with no outside funding, is altogether remarkable. A high school teacher turned freelance photographer, he came upon the Great Murals by accident. “I had gone to Baja California,” he recalls, “to work on a book about the old Camino Real, the road connecting the Spanish missions.” Then, a local rancher, guiding him around the backcountry, led Crosby to a cave containing prehistoric paintings. From that moment, he was hooked, returning again and again, by mule and on foot, pushing into lost canyons and trackless mountains. In 1975, he published the definitive Cave Paintings of Baja California, a documentary account of 230 painted caves, most of which he discovered himself. In 1993, thanks largely to his efforts, UNESCO designated some of the valleys where these paintings are found as a World Heritage Site.

Starting out from Crosby’s house outside San Diego in photographer George Steinmetz’s Chevy Suburban crammed with camping gear and camera equipment, Steinmetz, Crosby and I head south down the Trans-Peninsular Highway, the only paved road that runs the length of the landmass. Baja California sits atop a tectonic fault; now-dormant volcanoes created mountain ranges, like a spine, down the peninsula. The hard volcanic rock of the mountains is layered with strata of tuff, a water-permeable stone of volcanic ash that, over time, erodes away to expose very smooth overhang roofs (respaldos), made from the denser-rock stratum above. These surfaces, it turns out, are perfect for the creation of monumental paintings—provided an artist could reach the respaldo or, in the case of taller cave ceilings, construct scaffolds to do so.

“All you have to do,” says Crosby, “is spend some time with the murals to feel their power. But what keeps me coming back is their mystery. Who were the artists? How did they manage to do this? No one can really say.” Despite a growing belief that three different human migrations appear to have passed through the region in the past 11,000 years, no serious archaeologist will hazard a theory on who the artists were.

After two days of driving, the three of us fetch up in the quiet beach town of Mulege, about two-thirds of the way down the peninsula’s eastern coast on the Gulf of California. Brick and adobe buildings stand along narrow streets illuminated by strings of small, white lights that dangle above the sidewalks. Mulege is headquarters for a team of researchers from Mexico’s Instituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia (INAH), some of whom will accompany us into the mountains. We catch up with their lead investigator, archaeologist Maria de la Luz Gutierrez. Slim and soft-spoken, with rimless eyeglasses and dark ringlets falling to her shoulders, she spends the next two hours with us, poring over maps, photographs and notebooks.

The next morning, we pile back into the Suburban, the archaeologists leading the way in their four-wheel drive vehicles, and head north toward the mountains. Just a few miles out of town, we leave the Trans-Peninsular’s blacktop for a gravel road that threads inside the jumble of volcanic peaks to our west.

An hour turns into two. The cactusstudded peaks of the Sierra de Guadalupe rise nearly 5,000 feet on all sides. Four thousand feet below us, dry riverbeds, remnants of the winter rains and hurricanes that sometimes drench the landscape, braid through the bottom of each valley. Ficus trees, flowering shrubs and dozens of varieties of cacti thrive here, including the prickly cirio, looking like a green, inverted carrot drawn by Dr. Seuss. Lizards skitter ahead of us along the gravel track. “This place is a maze,” Crosby says. “It’s easy to get disoriented and in trouble.”

Finally, after several hours, we come to an outpost called Rancho de San Sebastian, a cluster of cinder-block-andplaster houses backed against a tall peak. We climb stiffly out. A few of the ranchers emerge from whitewashed cottages to inspect us. The people of San Sebastian don’t see many visitors, and they’re wary.

Once we exchange greetings, we begin trekking up an eroded, dry riverbed, then up a narrower dry-creek canyon, called a cañada. The canyon walls are dauntingly steep, sending a few of us sliding downhill in small avalanches of scree. After at least a half hour of scrambling under low brush up the incline, we emerge along the brow of a mountain. There, protected by an overhanging cliff, is a shallow respaldo shelter.

In the one nearest us, two vultures, rendered in black pigment, rise overhead, their wings spread. Three human figures painted in red and black—along with faded but recognizable representations of deer and bighorn sheep—grace the back wall. As with all the Great Murals, the figures depicted are, for the most part, life-size. Each seems urgent and fresh, with a touching immediacy transcending 3,500 years.

As I take in the mural, the INAH team has pulled out a digital camera, measuring tapes, notebooks and a GPS receiver (to fix a precise location and altitude). As the scientists work, Gutierrez points out the arrows, or flechas, that are drawn through the wings of the vultures and into the bighorn sheep. As the hunters pay homage to their prey across thousands of years, I ask Gutierrez, why here? Why not on the mirror-image respaldo on the canyon’s opposite side?

“At each site,” she answers, “one asks that question.” In certain cases, the choice of location seems obvious. “Some of these murals are near what were probably well-traveled trails, overlooking places where food and water could be found year-round.” Yet other cave paintings, she goes on, “exist up narrow, almost impassable box canyons. No one would go to those places unless they knew the paintings were already there.”

“That’s just one of the conundrums drawing me back here,” Crosby interjects. “Fundamentally, we’re asking ‘What were the artist’s motivations?’” He smiles and shrugs. “Be careful: you can spend a lifetime chasing that question.” That night, after 60 punishing minutes of driving up a dry riverbed to a wooded campsite deep inside the mountains, Gutierrez, Crosby, Steinmetz and I continue our speculations around a camp table over steaming bowls of beef stew. The paintings, Gutierrez says, exist inside a territory 300 miles north to south, and 25 miles east to west, within the perimeters of the peninsula’s mountain ranges.

Yet, while the murals are similar in size and overall technique, they also exhibit four distinct stylistic variations. In the north, throughout the Sierra de San Borja, they are monochromatic, realistic silhouettes of human figures, rendered in red. Moving south to the Sierra de Guadalupe—where we are now—the images take on new motifs, including the flechas we spied today. Here, the figures are ocher and white as well as red and black. They are often depicted wearing quirky headgear, spiky jester-like caps we can only assume had cultural or religious significance. And there are animals—bighorn sheep, for instance, and eagles. And sea creatures, from whales to manta rays.

Farther south, colored shading of figures, in crosshatched patterns, makes its appearance. Finally, in the southern foothills, the murals—while still large and well proportioned—evolve into blocks of textured color, highly abstract, barely recognizable as humans or animals.

“We believe the mural painters lived in the mountains, but they migrated seasonally down to the sea,” Gutierrez says. “When they made forays to the beaches, they may have exchanged information or techniques with other painters.” At some painted caves far back in the mountains, archaeologists have found abalone shells, which were likely used as scrapers, and other tools. “Obviously, these artists were nomadic,” Gutierrez says. “They ate the fruits and vegetables in one area, they hunted game there; when food became scarce they moved on.”

Last year, Gutierrez’s team, along with an Australian researcher, Alan Watchman, began taking tiny paint samples from perhaps 50 of the Great Murals. By analyzing them, they learned that cactus pulp was used as a binding agent. Eduardo Serafin, Gutierrez’s associate, and his colleagues have identified the place where some yellow pigment was mined, on a mountainside northeast of here. “At that site,” he explains, “you can actually see where they smashed away the side of the mountain to get to the colored volcanic rock. Then they carried that rock for long periods, sometimes across hundreds of miles, before using it. The paintings, undoubtedly, were carefully orchestrated, premeditated works of art.” But deeper clues to the people who created the Great Murals are harder to come by. “In terms of artifacts,” Serafin adds, “we have found only a few stone tools.”

The next morning, crosby, steinmetz and I strike out on our own. We are headed southeast through a maze of unpaved routes. Over the next two days, covering hundreds of miles, we pass only one other vehicle, a pickup truck traveling southwest. Traversing deserted valleys and mountain passes, we regularly have to pull up abruptly, clearing away boulders before we can continue on the gravel tracks that pass for roads here.

Cruising deepest Baja, I begin to understand how Crosby has been seduced by this rugged, alluring backcountry. We stop at San Borjitas, where 80 vivid figures crowd that expanse of cave ceiling. At Piedras Pintas (Painted Rocks), we clamber up a mountainside, reaching a cliff top after 30 minutes of hard climbing. There, overlooking desert, the rock face is etched with a marine menagerie: fish, manta rays, sea turtles and a hammerhead shark, still exuding menace from across the centuries.

At a site named after an old ranch near here, known as La Trinidad, we find a mural covering a 40-foot-high wall of pink volcanic rock. In the intensifying light, the pale stone seems to fluoresce.

Low down on La Trinidad’s wall—lit from above by the glowing rock—are two rows of small, aboriginal handprints, traced in white pigment. Higher up, dominating the space, stands a gracefully drawn buck, shaded in red pigment, its antlers branching artfully. A large fish, its form resembling that of a tuna, displays an anonymous artist’s poetic comprehension of pi-scine anatomy. Bones radiate out from a line stroke delineating the spinal column. “Look at that,” Crosby notes admiringly, “a prehistoric x-ray.”

There is a kinetic energy to the figures—especially the powerful buck—that recalls modernist works by Miro and Mondrian. The world has been pared to an ancient impulse: the need to pinion beauty, to create a record for posterity.

La Trinidad is a last stop before we make our way out to the paved surface of the Trans-Peninsular. We’re looping back to deliver Crosby to Mulege, where he’ll board a bus for the first leg of his return to San Diego. For the final stage of our journey, Steinmetz and I are crossing into country so trackless we will pack in on mules. “I’m going to forgo that hardship,” Crosby had told us. “But you must see the Arroyo de San Pablo.” To miss those murals, he insists, “would be like going to Rome and skipping the Vatican.”

We drive north out of Mulege for an hour and a half. Then, with the 6,000-foot peaks of the Sierra de San Francisco to our east, we turn off toward the mountains. There, we pick up a gravel lane that climbs the sierra’s side and crosses narrow ridgelines; eroded valleys fall away 1,000 feet. After bumping along the bad road lit by the last rays of sunset, we arrive at road’s end: the little settlement of Rancho de Guadalupe.

In the darkness, the outpost—a scattering of small, rough wooden buildings—looks desolate. At 5,800 feet, 40-mile-perhour gusts of freezing wind buffet the car, rocking it. Steinmetz and I pull on our heaviest clothes and hunt up our guide, boot-tough cowboy Ramon Arce. In the dirt-floored cook’s shack next to his house, Arce kindly offers us a feast of beef-and-cheese taquitos cooked on his propane stove.

“The paintings in the canyon are amazing,” Arce says. “Much larger, more beautiful than anything you have seen so far. And,” he adds, smiling, “the trip will allow me to get out of this freezing wind. It will blow like this for four or five days.”

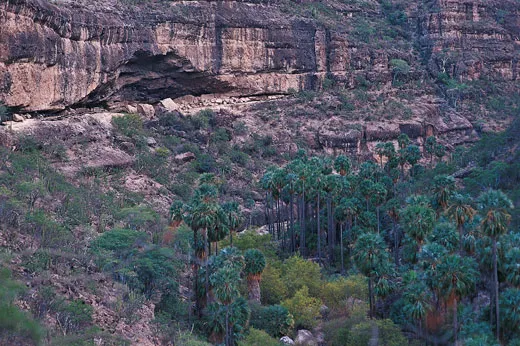

The next morning, just after sunrise, Arce rouses us, leading a string of mules. In no time, he has cinched cargo racks and saddles on the animals and loaded up the equipment boxes. As we mount up for the trip and follow a narrow trail out of the settlement, Arce sings traditional Mexican canciones to, he says, jolly along the mules. We start down a nearly vertical, 3,500-foot ravine, the spectacular Arroyo de San Pablo, a Grand Canyon minus the tourism. And as we drop deeper inside these protected walls, the sabersharp wind vanishes, to be mercifully replaced by bright sunshine and shirt-sleeve temperatures.

By the time we reach the depths of the gorge, six hours later, we can see a narrow watercourse running along the floor of the arroyo, lined by thick stands of palm trees. Across the arroyo, perhaps 100 feet up the canyon wall, I see the largest of all Baja’s Great Murals.

It stretches for nearly 500 feet along a shallow respaldo, virtually every inch embellished with male and female figures measuring 20 to 30 feet high. Equally outsize representations of mountain goats, rabbits, deer, antelopes, snakes, vultures, a whale, and handprints and cryptic starbursts, surround the human forms. Arce leads us down to the canyon’s floor, where we hastily unload our equipment, unburden the animals and—not even pausing to set up our camp—begin walking toward Cueva Pintada (Painted Cave). “Welcome gentlemen,” Arce says softly, “to a truly Great Mural.”

It is primarily because of Cueva Pintada—with its exceptional size and hundreds of paintings—that these valleys were designated a World Heritage Site. Some figures stretch 40 feet high. Whoever the painters were, they had a sense of humor. One artist incorporated a rounded lump of rock jutting out from a flat surface into his anatomically correct painting of a pregnant woman. Elsewhere, rabbits, zanily represented with lop ears slightly askew, munch grasses. A few of the largest human figures, wearing larky hats and kicking up their heels, seem to be dancing.

Still, it is two more hard days of exploring before I confront anything to compete with Cueva Pintada. This is El Brinco, or The Leap. Human figures, at least 15 feet tall, painted in red and black, crowd the underside of this nearly inaccessible respaldo. Drawings of gigantic deer, Brobdingnagian rabbits and an enormous fish add to the panorama.

I am certain no solitary artist could have created paintings so extensive. The requisite scaffolding would surely have required several individuals—and pack animals too. How long must it have taken to produce the pigment for images this size? Months? Years? Why would anyone create these works, masterful, miraculous, in so inaccessible a place? As the light turns from gray to blue to clear, El Brinco’s murals seem to waver on the volcanic rock. The splash of a creek echoes below; quail coo from the underbrush.

At this instant, I join the ranks of the Great Mural converts: another human attempting to commune with anonymous artists, the ancient ones who forged works of genius transcending both time and distance.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Don4x5.tif)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Don4x5.tif)