Coming Up Harlem

A revival of the fabled New York community inspires pride and controversy

At 6:30 one recent morning, Paulette Gay was already working at The Scarf Lady, her four-year-old boutique on Lenox Avenue, a faded Harlem thoroughfare showing vivid signs of renewal. Because the sidewalk is normally deserted at that hour, Gay was surprised to see someone peering in the store window—a giant of a man with a shaved head and piercing eyes. He looked familiar. Gay stuck her head out the door and said, “Aren’t you—?”

He was. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, the basketball great, who was born in the neighborhood and had long been a celebrated resident of Los Angeles , was back in Harlem . Gay asked him what he was doing out so early. “He explained that, being a very private person, he prefers to stroll around before anyone else is out,” she says. (At over 7- foot-1 and with a famous visage, he undoubtedly has trouble going unnoticed.) Abdul-Jabbar bought a town house in Harlem this past winter, according to Kareem Productions.

He joins a wave of black artists, activists, scholars and home-seekers lately drawn to one of the world’s signature African-American communities. The poet Maya Angelou and the singer Roberta Flack have bought houses in Harlem . Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr., who is among the nation’s best-known intellectuals, is on the hunt for a Harlem town house.

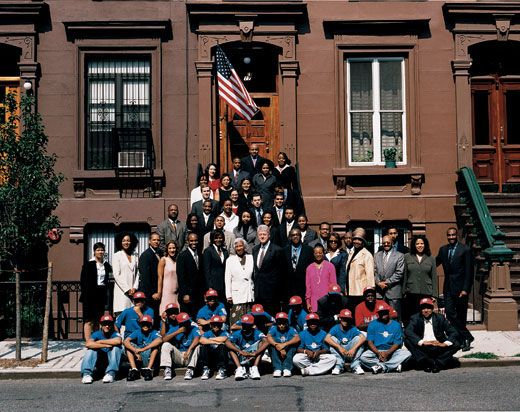

Contributing to Harlem’s cachet is America’s most renowned commercial tenant, Bill Clinton. His office occupies the top floor of a building on 125th Street, the neighborhood’s main artery. The former president has launched the Harlem Small Business Initiative program, which has provided a dozen struggling or fledgling businesses with professional consultants. “I wanted to be a good neighbor, not just a tourist attraction,” says the former president. “I wanted to make a difference in my community. And that meant bringing in resources and talent to help out.”

Harlem, a community in northern Manhattan that hit bottom in the 1980s when poverty, neglected housing and drug-related crime took their toll, is enjoying a lively second renaissance. Some Harlemites dismiss the resurgence as little more than a real estate boom, because the neighborhood’s magnificent 19th-century town houses are being snapped up at a rapid rate. You’ll also hear that the cultural scene doesn’t compare with Harlem's first flowering, in the 1920s, which was animated by extraordinary creativity in politics, the arts and especially the written word. But if it’s true there are no stand-ins today for fiery W.E.B. Du Bois, gentle Langston Hughes or patrician Duke Ellington, the second renaissance is still taking shape.

Highbrow, mainstream, pop, hiphop, avant-garde— Harlem's cultural and artistic revival is evident on nearly every block. At the partially renovated Apollo Theater, the curtain went up in July on Harlem Song, a Broadway-style musical directed by George C. Wolfe, producer of the Joseph Papp Public Theater/New York Shakespeare Festival. On St. Nicholas Avenue, the threeyear- old Classical Theater of Harlem recently staged King Lear in its garden court, with Paul Butler playing the title role as an African tribal chief in purple and cinnamon robes. In a 1909 firehouse on Hancock Place, George Faison, choreographer of The Wiz, a Broadway hit in the 1970s, is creating a performing arts complex with two theaters, three rehearsal studios and a library.

In another restored firehouse, on West 121st Street, is a small avant-garde gallery, Fire Patrol No. 5 Art. One re-cent night, a racially mixed crowd sipped wine from paper cups and witnessed a performance by a literary “commando” group called the Unbearables. “Museums were created to bring ugliness into the world!” one male trouper declaimed from the gallery floor. Another, a woman with short blonde hair, recites a poem titled “Balls.” Applause was vigorous but not unanimous. A young girl, trying to concentrate on her homework in a corner, piped up, “That was really nasty!”

The performance may not have been for everyone, but it indicates an atmosphere of artistic adventure. Over the decades, different New York neighborhoods have played host to the cutting edge—Greenwich Village in the 1950s, SoHo in the 1970s, the Lower East Side in the 1980s—and Harlem may be remembered as the place to have been at the turn of the millennium. As in other New York golden ages, some of the attraction has been cheap rent. Until a skyrocketing lease chased her north, French-born Christine Louisy-Daniel, the proprietor of Fire Patrol No. 5 Art, had a gallery on the Lower East Side . The grit of the neighborhood around her current venue doesn’t faze her. “I come from Versailles, which is beautiful,” she says. “But Harlem is exciting.”

Attesting to that excitement, a growing number of painters and sculptors with international reputations—Ellen Gallagher, Julie Mehretu, Chakaia Booker and Brett Cook-Dizney, to name a few—live and work in Harlem. Ousmane Gueye, a Senegalese sculptor who trained at the École des Beaux Arts in Paris and with Henry Moore in England, shows his art in the P.C.O.G. Gallery on Seventh Avenue, which he co-owns. “My father always turned the radio to music from Harlem when I was a child in Dakar,” says Gueye. “It was my dream to get here myself.” the word is dutch, reflecting Holland’s 1626 acquisition of Manhattan Island from local Indians, and Dutch Governor Peter Stuyvesant’s naming the village, in 1658, New Harlem, after a city in his homeland. Today, Harlem is informally divided into three parts. Central and West Harlem stretch roughly from 110th Street (the northern end of Central Park) to 155th Street, and are bounded on the west by the Hudson River and on the east by Fifth Avenue. East Harlem, which has been predominantly Latino, runs from around Madison Avenue to the Harlem River and south to 96th Street . Some 337,000 people live in Harlem, according to the 2000 U.S. census.

Like other urban neighborhoods settled by successive waves of immigrants, Harlem is a story of flux. In the 18th and early 19th centuries, prominent men such as the royalist Roger Morris and the patriot Alexander Hamilton built splendid houses (they still stand) in what was then a rural setting. In the late 1800s came elevated rail service, which brought prosperous commuters from as far away as City Hall, near Manhattan 's southern end. Two New York mayors, Thomas Gilroy and Robert Van Wyck, lived in Harlem . So did P. T. Barnum’s partner, James Bailey, whose turreted and gabled limestone extravaganza, built in the 1880s, still graces St. Nicholas Place . Around the same time, Protestant gentry erected impressive town houses around Mount Morris Park (now also called Marcus Garvey Memorial Park ). Next to settle Harlem were politically connected Roman Catholic families and also prominent Jewish families, including those of Richard Rodgers, Lorenz Hart, Oscar Hammerstein, Walter Winchell and Arthur Hays Sulzberger, grandfather of the current publisher of the New York Times. A relic of that period is the Temple Israel on Lenox Avenue ; it has a massively columned facade and looks built for the ages. But the synagogue fell into disuse once African-Americans started moving into the community and whites began moving out in large numbers. In 1925, it became Mount Olivet Baptist Church .

The 1920s renaissance was notable for jazz and literature, but it also embraced a newly formed black professional class of doctors, lawyers and architects. Nonetheless, opportunities remained limited for African-Americans in Harlem ; a double standard prevailed, with black laborers and entertainers generally working for whites. The Apollo Theater, which opened as a burlesque house in 1913, had white-only audiences until 1934. The Cotton Club, another legendary musical venue, displayed murals of a plantation with slave quarters. “I suppose the idea was to make whites who came to the club feel like they were being catered to and entertained by black slaves,” wrote bandleader Cab Calloway. William Allen, a fourth-generation Harlemite and a community activist, says blacks in the 1920s were performers, not customers. “They were not the owners of real estate,” he says. “It was like a Broadway production where the actors had no equity.”

Nor did Harlemites have much choice in employment, often having to settle for menial labor in the neighborhood’s many white-owned stores. That disparity changed somewhat after Adam Clayton Powell, Jr.’s boycotts in the 1930s, conducted under the banner “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work.”

Gerrymandering prevented Harlem from getting black Congressional representation until 1944, when Powell was elected to the first of 12 terms in the newly configured district—a career marred in the end by allegations of misused campaign funds and a reprimand by House leaders that the U.S. Supreme Court ruled was unconstitutional. He was defeated in 1970 by Charles Rangel, Jr., a Harlem native, who is now serving his 16th term. “My grandfather was lucky,” says Rangel. “He was able to get a civil service job as an elevator operator at the criminal court building. Like a lot of other guys my age, I got the hell out of Harlem by joining the Army.”

As a congressman, Rangel pushed for the creation of “empowerment zones” in battered urban areas, with federal funding and tax credits to fill the vacuum created by the absence of private lenders. In 1992, Bill Clinton signed empowerment legislation, which, matched with city and state funds, provided some $300 million in investment capital in Harlem. The money has percolated into commercial, educational and cultural projects. Rangel was also behind Clinton’s move to 125th Street, in July 2001. “I’d suggested Harlem to him while he was still president,” says Rangel, “but it seemed to go right over his head. Later, when he was catching hell for the expensive office space he took on West 57th Street, he called me to ask if Harlem was an option. I said, ‘Does the sun shine?’ He called on a Thursday. On Monday morning, I took his people to see the top floor at 55 West 125th Street. The owner kept saying there was one little problem, which was that a city agency had already leased the space.” Rangel and Rudolph Giuliani made the problem go away.

Clinton arrived at a time of rising disquiet among old-line Harlem businesses, which faced rising rents and new competition. “One thing that bothered me about my coming here was that it was likely to increase upward pressure on rents,” Clinton told me as we rode though Harlem in an SUV with his secret service detail. But Clinton’s consulting program for small businesses aims to boost their revenues and offset the increased costs that often accompany a hot market. “These businesses had low rents, but low revenues too,” he said. “They have to update how they operate or they might not survive. If this pilot program has the results I expect, then we’ll expand it all over New York and elsewhere in the country.”

One of Clinton’s education programs, Operation Hope, teaches economic literacy in several Harlem public schools. Another program works with VH1, the cable TV music channel, to donate musical instruments and provide music instruction to public elementary and middle schools in Harlem. “By 2004, no kid in any Harlem school will have to do without a musical instrument,” he said. As the motorcade rushed by numerous storefront churches, he added: “If you look at the history of Harlem, it’s the history of its churches and its music.”

Perhaps the most visible evidence of a revitalized Harlem is the new commerce on Clinton’s street. In 2000, an enormous Pathmark supermarket opened on 125th Street. Last year, with a boost from Empowerment Zone funds, Harlem USA, a 275,000-squarefoot shopping center between 124th and 125th Streets put a sleek face on the street, housing Old Navy, a Disney store, HMV music, Modell’s Sports, and a Magic multiscreen theater, one of several Harlem investments by basketball great “Magic” Johnson.

Those brand-name stores could be in any suburban mall—and that’s the point. For too long, national retailers stayed out of Harlem. Especially galling to Harlemites has been the absence of a chain bookstore. So the most eagerly awaited opening at Harlem USA was that in August of Hue-Man Bookstore, which bills itself as the nation’s largest black-oriented book emporium. Proprietor Clara Villarosa, former owner of a Denver bookstore, got a $425,000 Empowerment Zone loan.

Other parts of Harlem, though less crowded than bustling 125th Street, are also in the midst of a business boom. The same chain drugstores that overpopulate downtown are now in Harlem after years of conspicuous absence. Boutiques are popping up too. On Fifth Avenue just above 125th Street, a former private residence now called the Brownstone houses several stylish shops on three floors, including a jewelry store owned by a former buyer for Tiffany & Co., and a tearoom, where late-afternoon patrons may indulge in cucumber, watercress and curried-chicken sandwiches while drinking traditional and herbal teas.

Half a dozen new eateries have taken hold, from the upscale and raffish Jimmy’s Uptown, at 2207 Seventh Avenue, to the sedate Sugar Hill Bistro, situated in a 19th-century town house on West 145 Street. Sugar Hill is a nickname for a part of northwest Harlem in which wealthy blacks began to settle in the 1920s, who in the parlance had lots of “sugar,” or cash. On Mother’s Day, the bistro’s ground-floor lounge was filled with people as a singer belted out the words to “This Little Light of Mine.” The microphone was passed from table to table so diners could deliver the refrain: “Let it shine, let it shine, let it shine.” The easygoing warmth evident here, Harlemites will tell you, is a community trait. Indeed, it’s as easy to strike up a conversation with a stranger in Harlem as it is difficult in midtown.

The new Harlem pays homage to the old, as an owner of Sugar Hill Bistro suggested. The bistro is owned by three young black couples, all recently settled in the neighborhood, who never intended to become restaurateurs. “We just wanted to create a place where you get a high-quality cup of coffee, which was unavailable in the community,” says part-owner Dr. Dineo Khabele, a gynecologic oncologist. “Every landlord we went to said, ‘Why would you want to do that? Nobody up here will pay extra for gourmet coffee.’ ” Jumpstarted by a $300,000 loan from the Empowerment Zone, they bought a thenvacant town house and redid it top to bottom. The bistro has a first-floor bar leading to a rear garden, a second-floor dining room and a third-floor gallery and cultural space. “It reminds me of what I’ve heard about A’Lelia Walker’s upper-floor room where people could gather,” says Khabele, referring to the premier hostess of the first Harlem renaissance, a wealthy patroness of the arts who called her salon the Dark Tower, after a poem by Countee Cullen.

The rebound has been a long time coming. After the first renaissance was cut down by the Depression, grim decades followed. For many Harlemites, upward mobility meant forsaking the concrete jungle for a house with a lawn in Brooklyn or Queens, or close-in suburbs such as Yonkers and White Plains, where formerly off-limits housing was opening up to black families. “Integration emptied out our middle class,” says Anthony Bowman, owner of the Harlem Gift Shop and Tourism Center. “Harlem had the best name recognition in the world, and all these people moved to St. Albans, Queens.”

After the urban riots of the 1960s, the major avenues were renamed: Lenox Avenue became Malcom X Boulevard, Seventh Avenue became Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. Boulevard, and Eighth Avenue became Frederick Douglass Boulevard. Still, many Harlemites prefer the original designations. Some people with whom I spoke on Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard used the old name, 125th Street. At the area’s nadir in the 1980s, most of central Harlem’s housing was owned by the city in foreclosure for nonpayment of taxes—and by most accounts the city was an indifferent landlord, contributing to the community’s housing problems. A breakdown in the social fabric also occurred, some local observers say. “Drugs, despair, abounding vice, idleness, no strong family life,” is how those days are remembered by the Rev. Calvin Butts, minister of the Abyssinian Baptist Church, a powerhouse in the community’s affairs (and a leading tourist attraction).

Some middle-class African-Americans have stayed in Harlem for the duration, of course. Dabney and Amelia Montgomery, leaders of the Mother African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church on West 137th Street, the oldest black church in the state, bought their town house at 245 West 136st Street in the late 1970s, when a financial crisis made the city’s future look scary. Over brunch at Londel’s, an eight-year-old soul food restaurant on Eighth Avenue, they’re asked if buying back then was a pretty brave thing to do.

“Brave?” says Mrs. Montgomery.

“People like us have always been in Harlem,” says her husband. “We never worried about the ups and downs.”

Arthur Mitchell, founder of Dance Theater of Harlem, makes a similar point about the continuity of Harlem’s cultural institutions as we watch a pair of implausibly limber young dancers work out at the group’s studio on West 152nd Street. “Boys Choir of Harlem, Jazzmobile, National Black Theater, Studio Museum in Harlem, Apollo Theater, the Schomburg Center— they’ve all been here for 30 years or more,” Mitchell says. “And I founded DTH in 1968. I was born in the community, and I’m bringing it home.”

Still, few Harlemites doubt that the community has changed in the past decade. The city encouraged the improvement when it began transferring some of the Harlem properties it possessed to developers, often for as little as $1, and financing renovations. One shining example is West 140th Street, between Seventh and Eighth Avenues. As recently as 1994, it had been described as the worst block in Harlem by the Daily News; of 36 tenements, 8 had been abandoned to drug dealers and most of the others were eyesores. “I was reluctant to peep my head onto that block,” says Ibo Balton, director of Manhattan planning for the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development.

But the block responded quickly to an infusion of $33 million in city reconstruction funds. Today, it’s pleasant. The buildings’ fire escapes are painted aquamarine. The sidewalks are clean and lined with trees.

As in other urban neighborhoods, crime is still a problem, but, as elsewhere, Harlem’s rate of crime has dropped. In south Harlem’s 28th precinct, the murder rate fell by 80 percent over the past eight years, rape by 54 percent and burglary by 84 percent. In central Harlem’s 32nd precinct, murders numbered 56 in 1993, 10 in 2001 and 6 in the first nine months of 2002.

Community activism has also fostered recovery. In the late 1970s, state bureaucrats announced plans to convert a row of town houses fronting Mount Morris Park into a drug rehabilitation center. Mount Morrisites banded together and fought the plan, which was dropped. In 1984, the state established a minimum-security women’s prison directly on the park’s west frontage. Then, in 1990, the state moved to expand the prison into nine adjoining (and vacant) row houses. The neighborhood objected, and prevailed. Now those once-targeted row houses are being turned into condominums.

Abandoned properties persist on the best blocks, including the elite Strivers’ Row, but the value of much Harlem real estate has risen sharply. In 1987, a large Federal-style house on Hamilton Terrace sold for what was then a record price of $472,000. This year, a smaller house around the corner is under contract for $1 million. Nearby, a row house in “triple mint” condition sold for more than $2 million.

One hallmark of the second harlem renaissance is the return of young black people. Unlike their antecedents in the first renaissance, who lived behind “invisible lines and bars,” as the writer Eunice Roberta Hunton put it, well-to-do African-Americans investing in Harlem these days could live just about anywhere. They offer a spectrum of reasons for preferring Harlem.

“I think of myself as a nation builder,” Arizona-born Shannon Ayers explains of her motivation for coming to Harlem and opening a spa in a newly renovated, Empire-style building on Lenox Avenue, near the whitebrick town house she bought in 1998.

“I’m very attuned to my ancestry, so my spirits brought me here,” says city planner Ibo Balton of his move in the early 1990s from the Bronx to a rental property in a former school building on St. Nicholas Avenue. “It’s just a place I needed to be.” As a sign of the increasingly upscale times, the civil servant quips that he was probably one of the highest paid persons in his building when he got there but is now arguably the lowest.

Willie Kathryn Suggs, a former television producer turned real estate broker, says Harlem puts her at ease. “I wanted to live in Harlem when I came to Manhattan, but my father said no way,” she says. “So I got an apartment on East 44th Street. Women there assumed that I must be a domestic. They’d ask if I had an extra day. It didn’t matter that I was a TV producer at ABC, dressed to the nines. All they saw was my brown skin. Then I moved to the West Side, and white guys would jingle the change in their pockets and ask me if I was working. They thought I was a hooker!” In 1985, Suggs bought a Harlem town house, which she also uses as an office. “Up here,” she says, “people ask me if I’m a teacher. There’s a comfort level here that a person of color doesn’t have anywhere else. That’s why black folks move here.”

“For me, it was all about the architecture,” says Warner Johnson, an Internet entrepreneur. Johnson led a new generation into the historic Graham Court apartment house, located in Washington Heights. The 1901 building, with its interior courtyard and vast residences, “reflects the grandeur of another age,” says Johnson.

“For those of us who are creative, there is a sense of connectivity to Harlem,” says interior decorator Sheila Bridges, who also lives at Graham Court. “In no other place have African-Americans made such a contribution to the arts.”

In the'20s, white people went to Harlem primarily for entertainment. Today, they also go there to buy homes. Six years ago, Beth Venn and Tom Draplin, who were then renting an apartment in Washington Heights, began a search for a place big enough to raise a family. For the price of a smallish apartment on the Upper West Side, says Venn, they bought a big 1897 house on Hamilton Terrace, around the corner from Hamilton Grange, which was built by Founding Father Alexander Hamilton.

Tom, an architectural illustrator, and Beth, curator of software mogul Peter Norton’s art collection, both grew up in “whiter than milk” Midwestern communities, says Beth. “We really wanted our kids to grow up with other cultures and histories,” says Tom. But friends and family expressed concerns about their safety. The couple hesitated even to mention the property’s location to her father. But when he visited from Illinois to attend their wedding, she recalls, “the people from across the street brought us a bottle of champagne and took Dad over to tour their house. The outpouring of neighborliness was powerful and put everyone at ease.”

Tony and France-Yanne Dunoyer, originally from French Guadalupe, moved to Convent Avenue three years ago into an 1890 eclectic Victorian house that they have slowly restored. A worker spent almost a year refinishing the elaborate interior woodwork. An electrician installing wiring for sconces discovered a large, double-sided fine mahogany pocket door hidden in the walls. On weekends, the couple hunted for the antique furnishings, which, along with the 1904 Steinway grand piano in the music room, now fill the spacious house.

As Harlem steps into the 21st century, many residents worry that its new prosperity may bring a loss of identity and community. Moreover, some residents are being left behind or displaced, they say. “It’s troubling that the working classes and people who have been here a long time can’t buy property,” says William Allen, the activist and Democratic Party organizer. Louisy-Daniel, the gallery owner, tells of a neighbor who had to vacate her apartment when the landlord raised the monthly rent from $650 to $2,000. “We’ve been put out,” the woman told her. Kira Lynn Harris, an artist-in-residence at the Studio Museum, bluntly articulates a question on the minds of many: “Is Harlem slipping out of the hands of black people?”

Indications are that the community’s makeup is changing. Suggs, the broker, estimates that half of her recent home sales are to whites, Asians or Hispanics— more than double the rate five years ago. Still, most Harlem renters are black, and the community’s elite town house blocks remain largely in the hands of African-Americans. On Convent Avenue between 142nd and 145th Streets, several richly detailed houses sold in recent years went to black people, including a baronial corner house featured in last year’s hit movie The Royal Tennenbaums. And while a lot of major development in Harlem is funded by firms that whites control, a Harlem-based company run by African-Americans, Full Spectrum Building and Development, is constructing a 128-unit condominium at 1400 Fifth Avenue. Among other things, the $40 million project will be the first building in Harlem with geothermal heating and cooling.

A longer view of the race issue is taken by Michael Adams, author of the newly published Harlem Lost and Found and one of the community’s most ardent preservationists. Adams tells of attending a dinner party in a fastidiously maintained, century-old Harlem town house. One guest griped about a newly arrived white family on his block who had complained about noise coming from a revival meeting. Another guest bemoaned white neighbors who called the police about a loud party. “Why don’t these people go back where they came from?” someone asked.

“None of this would have been said, of course, if a white person had been at the table,” Adams says. “As I listened to their complaints, I imagined hearing voices in this same dining room eighty years ago. The words were the same, only the colors were reversed.”

Harlem is defined by a set of geographic coordinates, to be sure, but also by a feeling, or sensibility. For that reason, the Morris-Jumel Mansion on Edgecombe Avenue at West 160th Street may be said to be part of Harlem, though it’s technically just north of the 155th Street administrative boundary. The stately home, which dates from 1765 and which George Washington used as his headquarters for a month during the Revolutionary War, incorporates perhaps the first octagonal room in the Colonies. Shady gardens surround the house, which, improbably, sits on a kind of schist proscenium overlooking the towers of an enormous public housing project on the site of the old Polo Grounds, where the New York Giants played baseball. The Morris-Jumel Historic District, as the neighborhood is called, feels like Harlem, with its dignified homes, including 16 Jumel Terrace, which once belonged to the incomparable singer, actor and fighter for social justice, Paul Robeson.

If you stand under the shade of the oak and hackberry trees on the Morris-Jumel grounds late on a Sunday afternoon, you might hear the most persuasive reason for feeling that you’re in Harlem: jazz, wafting out of an apartment house across the street. The sessions take place in the third-floor apartment of Marjorie Eliot, an actress, playwright and jazz pianist. Eliot’s 28-year-old son, Phillip, died of kidney disease in the summer of 1992. To mark the first anniversary of his death, she hired jazz musicians to play on the lawn of the mansion. Eventually, she had musicians play in her apartment on Sundays. Her living room, decorated since September 11 with a small cutout of an American flag, holds several dozen metal folding chairs. She serves juice and cookies. Though a tin is passed around for donations, no contribution is required. “Clubs are so costly,” she says, “and musicians don’t get a chance to stretch out and play. I want people to experience music uncompromised by commercial constraints.”

The nightclubs of the first Harlem renaissance are gone. Last June, a plaque was belatedly dedicated to mark the Seventh Avenue site of the Savoy Ballroom, once the “Home of Happy Feet” and the Lindy Hop. It’s now a housing project. Nothing marks the site of the original Cotton Club a block away. A club by that name today on West 125th Street caters largely to tourists, with offerings like a Sunday gospel brunch.

The Apollo Theater, which introduced or helped launch the careers of artists such as Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughn and James Brown, deteriorated over the years, despite the popularity of its Wednesday amateur night shows. A ballyhooed 1992 renovation barely stemmed the decline, and a more extensive, $53 million renovation is under way. But a widely trumpeted plan to incorporate the shuttered Victoria Theater a few doors away was postponed in September due to fears that the economic climate could result in lowerthan-budgeted revenues and donations.

The postponement was a blow to some in the community and a snag in its otherwise dazzling comeback. But the second Harlem renaissance is far bigger than any one reconstruction project. Investment in the place remains strong, and its undeniable mystique continues to grow. You can sense that energy at the sold-out performances of Harlem Song, the Apollo’s first long-running show, in which a supercharged cast dances and sings its way through 20 musical numbers touching on the community’s history. On the night I attended, the audience looked prosperous and included members of the city’s financial and political elites. The most familiar songs, like 1933’s “Drop Me Off in Harlem,” were from another heyday, but the natty throng and the limousines jockeying at the curb were very much of this one.