Climate Change Tourism in Greenland

With 80 percent of the ice that covers the island melting, Greenland has become a hot travel destination

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Greenland-restaurant-Nuuk-631.jpg)

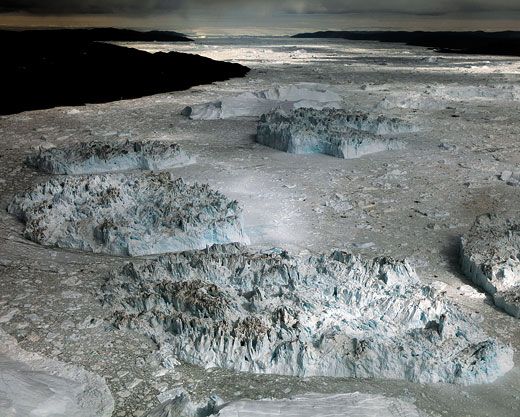

“When you’re flying into Greenland, you almost feel like you’re going into outer space,” says Molly Schriber, a 22-year-old Houston native and Elon University graduate, who visited the island last year on a weeklong study tour. “You look at the ice sheet, and it’s like nothing you’ve ever seen before.”

More and more people are seeking that experience. Some 30,000 people reached Greenland on cruise ships in 2010— twice the number in 2004—with an estimated 30,000 more coming by air. What’s prompting many of these visits is global climate change; in 2010, according to the World Meteorological Organization, the temperature in Greenland and the Canadian Arctic was an average of 5 degrees Fahrenheit above normal. One result has been more seasonal melting of the Greenland ice sheet.

“Some people we met there were saying things like, ‘I want to visit Greenland before it completely disappears. I want to see polar bears before they are completely extinct,’ ” says Alban Kakulya, a photographer in Geneva who spent three weeks in Greenland in 2009. His photographs manage to capture the island’s otherworldly beauty as well as the incongruity of pampered, sneaker-clad cruise passengers milling around what was once regarded as a forbidding landscape.

The world’s largest island (not counting Australia), Greenland is the size of Mexico and yet has only 56,000 residents and 75 miles of roads. More than 80 percent of the landmass is covered by ice, in some places two miles thick. Most people live along the coasts in traditional villages or towns such as Nuuk (pop. 16,000), the capital and largest city. The nation is a protectorate of Denmark but has an independent government.

Greenlanders themselves seem torn about climate change. Some say melting ice will expose land for oil drilling, mineral exploration and food production. “One positive thing is that in south Greenland the climate is getting warmer, and we are looking more into how we can create our own crops,” says Malik Milfeldt, of the Greenland Tourism and Business Council.

Others worry about the effects on traditional ways of life. With less summer ice cover, hunters who use dog sleds are limited, says Hanne Nielsen, who teaches Greenlandic and Danish languages in Nuuk: “Climate change has had a really harmful influence on people’s lives, not only professional hunters and fishers, because ordinary people also fish and hunt.”

Kakulya, the photographer, and others are concerned that encouraging tourists to observe the effects of climate change, which is partly caused by carbon dioxide emissions from burning fossil fuels, only worsens the problem. “The more you want to see the effects of climate change, the more you want to travel, the more CO2 you are going to emit,” says Kakulya.

But tourism might be just the thing to get the world to take global warming seriously, says Milfeldt: “If people come to Greenland and see how much the glaciers have been retreating and realize it’s for real, and change the way they use energy, then maybe the net benefit will be for the globe, for the climate.” In that view, the real question isn’t whether people should travel, but how they should live when they get back home.

Joseph Stromberg is the magazine’s editorial intern. Geneva-based photographer Alban Kakulya calls Greenland “one of the last frontiers of the tourist industry.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)