Canyoneering: Much More Than a Hike in the Park

The “Average Joe’s” extreme sport takes athletes high atop mountains and deep into canyons

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/canyoneering-man-bridge-631.jpg)

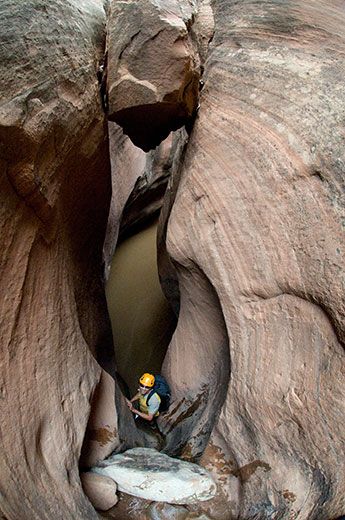

“Whoo hooo” echoes through Yankee Doodle slot, a rocky gash in Dixie National Forest, not far from Utah’s Zion National Park.

My son, Joe, is celebrating midway down the canyon’s biggest rappel, a 130-foot drop that starts with working your way around a large boulder, then requires a mid-course correction, swinging from one slab of angled rock to another.

At the sandy bottom, in the shade of a lonely tree, we rest and enjoy the view. “It looks like someone took a knife and carved the rock,” says my daughter, Ann Burns.

She’s gazing up at the fluted wall of golden Navajo sandstone, encircling a patch of sky blue. This is our first foray into canyoneering, a relatively young sport (called canyoning in Europe) combining climbing, rappelling, bouldering, swimming and hiking. Yes, it’s thrilling, an opportunity to explore stunning underground Edens. But it’s also an exercise in problem solving. Around every blind corner is a new challenge.

Over the course of a few hours, we’ll clamber over boulders, “chimney” over dank water between narrow walls, bracing our backs against one side and our feet against the other. We’ll cautiously climb down a boulder only to drop into a cold, muddy trough of foul-smelling water. Later, we’ll solve the problem of escaping a “keeper hole,” a round pool of uncertain depth. It turns out there is more than one solution, including finding a hidden underwater foothold or using your momentum and well-placed hands to create the “beached whale” technique, flopping out on your belly.

The walls swoop in tight, then flare out, the rock seeming to flow. The light from above casts golden highlights, then deep, foreboding shadows. The rock, sculpted by water over millions of years, seems to flow in rivers of butter and camel sandstone sometimes varnished in streaks of black. At times, it’s like walking into Jules Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth.

“It’s kind of like the Average Joe’s extreme sport,” says Jeremy Draper, who has been guiding canyoneering trips for the better part of a decade. “You see some cool stuff and get a little excitement sliding down ropes.”

Darren Jeffrey is the president and founder of Alpine Training Services, based in Los Angeles (yes, L.A. – he says there are about 60 canyoneering routes in the city). “The appeal for the average person is there’s a high level of perceived risk and a manageable level of actual risk,” he says. While accidents are rare, people have died canyoneering, drowned in flash floods and “keeper holes” they couldn’t escape. Every experienced canyoneer seems to have a story or two about a close call.

Perhaps the most famous canyoneering accident is Aron Ralston’s misadventure as depicted in the recently re-released film 127 Hours. Ralston was navigating Utah’s Bluejohn Canyon’s narrowest section when a chokestone fell, trapping his hand, requiring him to amputate it below the elbow after five days. Disaster aside, audiences of the movie still got a sense of the rocks and water allure of the sport.

Even though the sport started in Europe during the 1970s, Utah is the capital of the sport, attracting rock climbers and mountaineers. Other regions, including the Grand Canyon, Death Valley and Lake Powell have since opened up.

Jeffrey is enthusiastic about using new techniques in Hawaii, New Zealand, where volcanic rock and foliage highlight the hikes, and the West coast of the United States, where serious swimming is need to navigate water canyons and rappel down waterfalls. “It’s beyond what most people can comprehend when they think of canyoneering,” he adds. “We like to be out where it’s pristine and lush with fast-moving water.”

Steve Ramras, who climbs up mountains or clambers down into canyons for 120 days a year, started canyoneering in the late 1970s with college buddies. He’s watched as the sport has slowly become more popular and more technical. “I used to go a whole season without seeing footprints in many of the canyons,” he says. “That’s not necessarily true anymore, but there’s still a limited number of canyons that there’s information on (and amateurs explore).”

Tom Jones, a Utah guide who also sells gear, says techniques have improved so that the sport is safer than before. “But we’re also doing a lot harder canyons,” he adds. “So it may be a good thing we didn’t find some of the canyons we’re finding now back then.”

Ramras, 56, owns a janitorial service in Fort Collins, Colorado, and on the side has written a series of stories about his canyoneering journeys, Tales of an Incompetent Adventurer with titles like “Close to the Edge, and “The Mud, the Blood, and the Fear.” This spring, he will join a month-long hybrid expedition running the whitewater of Colorado River through the Grand Canyon and exploring slot canyons.

Canyoneering, Ramras notes, is different from climbing. If you’re climbing and can’t go any further, you rappel down to the ground and walk out. In canyoneering, once you rappel down into a slot and pull the ropes behind you, you’re committed. “There are all sort of levels [of difficulty] of canyons,” he says. “The majority of them are relatively easy. But there are still some out there where you can run into some pretty big surprises.”

He recalls doing one “beginner” canyon after a snowstorm. Suddenly, what were usually easy strolls over slick rock became dangerous and challenging.

Ramras and Jones and a few others created “Freeze Fest” in the North Wash of Utah, which celebrated its ninth anniversary earlier this year. It’s an extreme, adult camp-out beginning on New Year’s Eve. The brave and the chilly get up each morning and decide which canyons are “relatively safe” to explore. This year, it rained and then snowed, and temperatures dipped into the teens. Still, more than 30 people showed up.

“We refer to it as the stupid idea that caught on,” he says, dryly. “Margins for mistakes are low that time of the year. We don’t recommend the activity for the general public.”

The duo build teams to tackle the mystery and challenge of unexplored canyons. “Forming a group of people who can bring their expertise to bear in a challenging environment is its own reward,” Ramras says.

“Half the time I’m really confident and I don’t have any qualms,” Jones adds, “and then half the time it seems like a really stupid thing.” They walk the rims, if possible, to get a sense of what’s below. They may send someone rappelling over the side for a look. In some instances, a team on the rim may observe, ready to drop a rope and help those below climb out.

“It’s a lot like fun, but different,” Ramras says, laughing, a phrase favored by veteran canyoneers. For Jones, more than a decade after his first sojourns through the slots, the appeal endures.

“Every day in a canyon is just really fun,” Jones adds. “There are canyons I’ve done guiding a hundred times, but every time I go out there I’m still impressed by their beauty.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jim-morrison-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jim-morrison-240.jpg)