This Park in Ecuador is One of the Most Biodiverse Places on Earth

Yasuní National Park in the Amazon rainforest may have more species of life than anywhere else in the world

Deep in the heart of Ecuador's Amazon basin, in the shadows of the Andes and below the equator, lies what may be the most biologically diverse place on the planet. Yasuní National Park in eastern Ecuador is home to millions of species of plants, birds, insects and mammals. It teems with so much life it leaves people lost for words, says Dr. David Romo, co-director of Tiputini Biodiversity Station-Universidad San Francisco de Quito. “People get stuck on awesome. It is hard to use too many words other than awesome because, well, it is,” Romo says with a laugh.

Whether it’s humongous kapok trees, hairy tarantulas, squawking toucans, jumping spider monkeys or fierce jaguars, the diversity of organisms inhabiting Yasuní is astonishing. What is truly hard to fathom, though, is that little of the park has actually been studied. The Tiputini Biodiversity Station was established in 1994 and while scientists have since taken on multiple projects—for example, a recent project identifying a new species of tarantula with distinctive tiger-like marks—there is still much to explore. “If we compare the area of Yasuní to a pillow, [the amount of] information we have is equal to two needle heads on that pillow,” Romo says.

There is no definitive answer to the question of why or how Yasuní became so biologically diverse—the causes may include its high annual rainfall or low variation in temperatures. The park has also been called “an ecological bull’s-eye” due to the fact that it sits at the base of the Andes, along the Amazon and close to the equator—three distinct ecological systems converging to create a wholly unique area.

The park’s abundance of natural resources has turned Yasuní into a battleground of interests, however. While illegal hunting and logging have existed here for many years, the discovery of oil in 1937 underneath the fertile soil of the rainforest created a new threat.

“Oil exploitation” has been going on in parts of Yasuní since the 1970s, but it wasn’t until 2007 that Ecuadorian president Rafael Correa proposed a plan to protect the rainforest from drilling. The highly controversial Yasuní-ITT initiative called for $3.5 billion in international donations—about half of the revenue that Ecuador estimated they would have gotten by mining the 850 million barrels of oil under Yasuní. In return, oil drilling would be banned in the area. By August 2013, with only millions pledged and actual donations falling well short of the goal, the initiative was abandoned. After saying “the world has failed us,” Correa approved oil drilling in previously untouched parts of the park.

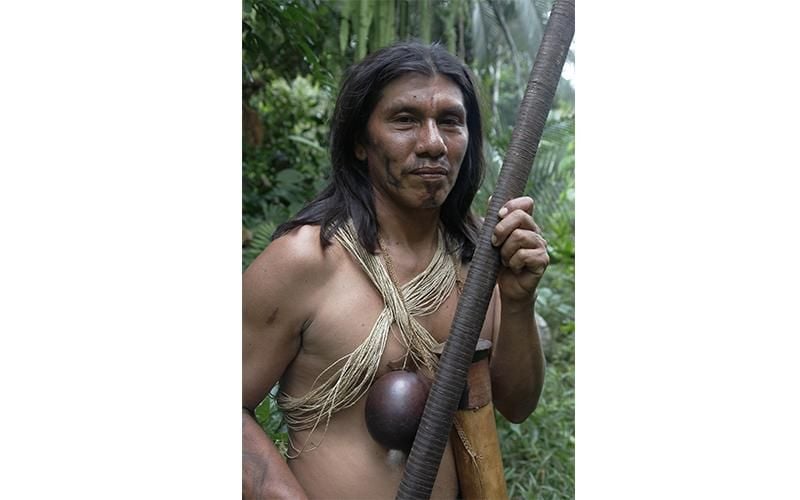

As this battle continues to rage, Romo knows that one of his jobs is to convince people of the utilitarian reasons for protecting the diversity of Yasuní. “The future of humans, the future of Earth, and the future of life as we know it will depend on how much humans master the understanding of genetic functioning and how we incorporate genetic information from our environment into our lives,” says Romo. He goes on to explain that local indigenous peoples —such as the Waorani, the Kichwa and other tribes living in voluntary isolation—have everyday uses for hundreds, if not thousands, of the species in Yasuní. “It is not just protecting biodiversity, it is also about protecting the people that evolved around that biodiversity for many years. It’s protecting that knowledge,” he says.

As awareness of the immense biodiversity of Yasuní has increased throughout world, it has also lead to an explosion of ecotourism. According to Romo and other sources, ecotourism can be a valuable conservation method, bringing much-needed dollars, awareness and jobs to the area. With many different travel lodges operating in the area under strict guidelines, there’s an opportunity for the adventure of a lifetime.

Even for Romo, the experience of being in the rainforest is still magical. “I have been going there since I’ve been nine years old. There isn’t a single time, to this day, when I make a trip, that I don’t end up seeing something for the first time ... it’s just amazing the things that are happening in Yasuní.”