Acadia Country

Anchored by the spectacular national park, the rugged, island-dotted coastal region of Maine distills the down east experience

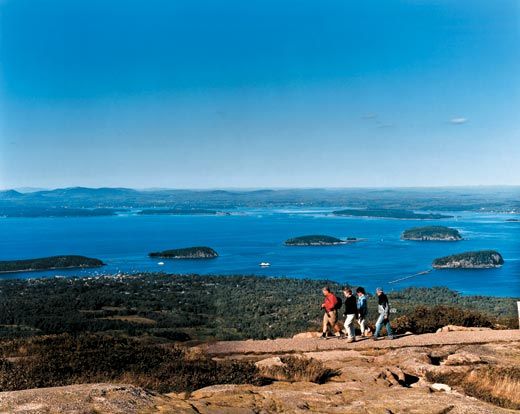

At only 1,530 feet, Mount Desert Island's Cadillac Mountain, in Maine's Acadia National Park, lays a singular claim to fame: it is the highest point on the eastern coastline of the Americas, from Canada all the way south to Rio de Janeiro in Brazil. But for anyone standing on Cadillac's summit on a brilliant summer afternoon, it's the view, not the statistic, that dazzles. To the west, ponds and lakes glisten in dense forests. To the east, a green tapestry of pine and spruce trees stretches to the outskirts of Bar Harbor. Beyond that seacoast village, yachts and sailboats ply the icy Atlantic waters off the four Porcupine Islands in Frenchman Bay.

At low tide, it's possible to cross the sandbar separating Bar Harbor from its closest offshore island. But now, in early afternoon, the tide is rising: whitecapped waves crash against a pink-granite coast. Each year, more than four million visitors converge on the summer playground known as the Acadia region of Maine, centered on 108-square-mile Mount Desert Island and the national park, and stretching from the Penobscot River on the west to the eastern border of Hancock County. "Acadia," or L'Acadie to the early French adventurers, likely derives from a corruption of Arcadia, the remote province in ancient Greece portrayed in legend as an earthly paradise.

Acadia has attracted warm-weather travelers for nearly 150 years. In the late 19th century, the barons of the Gilded Age, among them Rockefellers, Morgans and Vanderbilts, summered here. Initially, they were drawn to Mount Desert Island by their admiration for the works of several New York and Boston artists, including Thomas Cole and Frederic Church, who had come here in the mid-1800s to paint the isolated wilderness. Their patrons wanted to experience—as well as own—the scenery depicted in these works. "They were people with Newport ‘cottages' who wanted to get away from traditional summer resorts," says Marla O'Byrne, president of Friends of Acadia, a nonprofit organization created in 1986 to help protect and maintain the national park.

The wealthy vacationers soon built manors and gardens on a grand scale. Yet they also understood the need to protect the wilderness around them. Several decades earlier, Henry David Thoreau had warned in The Maine Woods that unchecked expansion of the lumber industry was stripping Maine of its splendid pine forests. Voicing a then radical notion, Thoreau claimed that the pine was "as immortal as I am, and perchance will go to as high a heaven, there to tower above me still." At first, few among the Newport set may have shared Thoreau's sensibilities. (Indeed, some had made their fortunes from lumber.) By the late 1800s, however, new technologies for processing timber were threatening even the summer refuge of the very rich. "The invention of the portable sawmill is what really scared them," says Sheridan Steele, superintendent of Acadia National Park since 2003.

Beginning in 1901, the Rockefellers and others bought up huge tracts of Mount Desert Island's forests, setting the land aside for eventual recreational use by the public. They lobbied Washington to declare this wilderness the first national park east of the Mississippi; Congress did so in 1919. The individual most responsible for the creation of the park was George B. Dorr (1853-1944). His friend, Harvard University president Charles W. Eliot, a summer resident of Mount Desert Island, called for an association of like-minded neighbors to protect the island's natural beauty. The Rockefellers, Morgans and other families responded generously. Mount Desert received its name from the French explorer Samuel de Champlain, who in 1604 described the Isle des Monts-Déserts ("island of bare-topped mountains").

John D. Rockefeller Jr. (1874-1960) donated huge tracts of land to the park. "Of course," adds his grandson David Rockefeller Jr. (who spends each August on Mount Desert Island), "his unique contribution was helping to design the carriage roads that thread through the park and make it so accessible to horseback riders, cyclists and pedestrians." Between 1913 and 1939, David's grandfather built 45 miles of horse-drawn- carriage trails and stone bridges on the 11,000 acres he owned before donating the land to the park. The trails forestalled the growing menace of automobiles, today confined to the Loop Road, a 20-mile, two-lane thoroughfare on the eastern side of the island.

Acadia National Park expanded piecemeal to 35,000 acres—the last major donation, of 3,000 acres, from the Bowditch family, was made in 1943. All but a few thousand acres lie on Mount Desert Island; the remaining parcels are scattered on smaller, nearby islands. Three miles southwest of Mount Cadillac, the cold, clear waters of Jordan Pond—actually a lake formed by glaciers 10,000 years ago—are flanked by Penobscot Mountain on the west and by a formation known as "the Bubbles," a pair of rounded mountains lying immediately to the northeast. A flat trail skirts Jordan's 3.6-mile shoreline. One of the original Rockefeller carriage trails, screened by pines, birches and maples, follows a ridge that rises 50 to 200 feet above the water. (Today, bicyclists pedal its dirt-and-gravel surface.)

Jordan Pond also serves as a starting point for treks to Penobscot Mountain or the Bubbles. Acadia Park's capacity to accommodate just about any visitor, whether a picnicker or a serious hiker, in so limited a space—while retaining its wilderness character—makes it uniquely successful. "You get the feeling you are in a much larger park," says superintendent Steele.

Since the late 1800s, when privileged vacationers first settled here, the town of Bar Harbor (pop. 4,820) has been Mount Desert Island's largest community. The original lavish residences reflected architectural styles ranging from Colonial Revival to Italianate. Guests often arrived by yacht, their hosts awaiting them at private docks and whisking them up to broad porches overlooking the harbor, where cocktails were served.

This charmed existence ended with the great fire of October 1947, which incinerated thousands of acres of forest in Acadia National Park and roared into Bar Harbor itself. "It divides the town's history into B.C. and A.D.," says year-round resident James Blanchard III, whose 20-room, white-columned Colonial Revival-style house dates from 1893. As the blaze approached, panicked inhabitants crowded on docks awaiting evacuation, or worse.

At the last moment, the wind shifted; the blaze retreated toward the forest. But as flames leapt from roof to roof, many of the mansions—some 60 in all—were destroyed. Blanchard's house, its roof shingled in asphalt rather than wooden shakes, was spared, although some of the towering pine trees in the garden bear scorch marks. "The fire flattened Bar Harbor," says Blanchard, who today leads efforts to preserve the remaining showplaces. "Town officials decided to shift the community's focus from elite to mass tourism, and encouraged the development of motels, inns and commerce. The old guard didn't like the hurly-burly and moved to Northeast Harbor." That community (pop. 527), still resolutely posh, lies 12 miles south.

During the summer, Bar Harbor's Main Street is thronged with vacationers served by boutiques and restaurants.Yet only a couple of blocks away, on the edge of the Atlantic, the town can seem as tranquil as old-timers remember it. A gravel path skirts the harbor along rocky beaches, where families wade in frigid waters at low tide, and continues past the few surviving mansions.

The only one permitting limited public access is the 31-room La Rochelle, completed in 1903 for George S. Bowdoin, a partner of J. P. Morgan. It was, according to the property's former caretaker, George Seavey, the first Bar Harbor residence with electricity; even its two doghouses reportedly boasted lights and running water. The gardens were designed by the distinguished landscape architect Beatrix Farrand (1872-1959), who also created Washington, D.C.'s Dumbarton Oaks. (Her garden at La Rochelle no longer exists.) The estate was sold in the 1940s to Tristram C. Colket. In 1973, the Colket family donated the property to a nondenominational Christian charity, the Maine Sea Coast Mission, now headquartered here.

In 1905, two Congregational clergymen from Mount Desert Island had organized the Sea Coast Mission to improve the health and spiritual well-being of lobstermen, farmers and their families living on a score of islands along the coast from Eastport to Kittery. Physicians and ministers, transported on a Mission vessel, visited islanders frequently. "We still take nurses out there," says Seavey. The Mission usually carries a minister on board to help lead services in island churches and chapels, or occasionally on the vessel itself.

Nowadays, most visitors reach the outer islands by ferry from Mount Desert Island. The Cranberry Isles—one to five miles to the south—are popular destinations, with boat service from Southwest Harbor to Great Cranberry Island and Islesford, both ideal for biking. Fewer tourists go to Long Island, eight miles out at sea and reachable by a Friday, round-trip passenger ferry operating April to November out of Mount Desert Island's Bass Harbor. Long Island is home to the tiny village of Frenchboro, famous as a traditional center of lobster fishing. Months earlier, I had happened across Hauling by Hand, Dean Lawrence Lunt's 1999 account of growing up there. "My view of island reality," he wrote, "is a heritage of endless labor, the sea, raw winter days, glorious summer mornings and crisp fall afternoons on the Atlantic Ocean."

There is but one overnight room available on the island; Frenchboro's tourists are day-trippers, most arriving by yacht or sailboat. On a cool July morning, I am the sole passenger aboard the ferry as it heads into a pea-soup fog. The only visible objects during the crossing are lobster buoys, bobbing a few feet off starboard and signaling lobster traps at the bottom of the Atlantic.

Dean Lunt greets me at the mist-shrouded Frenchboro dock on the northern end of the island; the 44-year-old author has offered to act as my guide. Owner of Islandport Press in Portland, a publisher of books specializing in Maine and its history, Dean is a descendant of the clan that first settled Frenchboro in the 1820s. Around 1900, it became an outpost for lobster fishing with nearly 200 inhabitants. By the early 1970s, however, the island's population had dwindled to fewer than 40, clustered on a deep, narrow inlet protected from all-too-frequent storms. At one point, Dean had been the only pupil in the one-room school. "T here were no phones [here] until I was 17 years old," says Lunt, as we drive in a pickup truck to his parents' home, less than a mile away.

In recent years, record harvests of lobster and a surging demand for the delicacy have brought near-prosperity here. The population has increased to about 70, including 14 students in what is now a two-room, white-clapboard schoolhouse offering instruction through the eighth grade. (Most youngsters then attend school on Mount Desert Island.) Just about everyone has access to satellite television and broadband Internet.

Many houses–wood-frame structures from the 1800s and early 1900s for the most part—appear to be under renovation, their tiny rose gardens fenced to discourage the deer that abound on this nine-square-mile, flounder-shaped island. Newly expanded houses encroach on family cemeteries clinging to steep slopes above the harbor. "Relatives going back to my great-great-great-grandfather are buried just over here," says Lunt, pointing to a grassy plot a few hundred yards from his parents' home. The white-marble tombstone of a Civil War veteran reads: "Hezekiah Lunt, private, July 2, 1833 to January 29, 1914."

When the sun burns away the fog, I follow Lunt down a narrow path and wooden stairway from his parents' house to the docks. Lobster boats unload their catches at the wharf, where they are weighed and purchased at $6.75 a pound by Dean's father, David, 70, proprietor of Lunt & Lunt Lobster Company, founded by the family in 1951. (Both of Dean's brothers, Daniel and David, are lobstermen.) There is no single explanation for record catches along Maine's coast during the past five years. Dean Lunt believes that a major reason is the overfishing and sharp decline of cod, a predator of lobster fry.

Some of the catch ends up at Lunt's Deli, where day-trippers, headed for Eastern Point Beach, about a mile away, stop to purchase freshly made lobster rolls. We set off in the opposite direction, along a winding dirt path through berry patches and apple trees to Gooseberry Point, a mile distant on the western side of the island. Here, pine and spruce trees face open sea. "In summer, there are porpoises, seals, whales—and sometimes deer swimming over from other islands," says Lunt. "My wife, Michelle, and I got engaged here."

For the remainder of my visit, we stroll the single paved road, a mile or so stretch looping past Frenchboro's landmarks. The white-clapboard Congregational Church dates from 1890. Dean was baptized here; a minister from the Sea Coast Mission leads services one Sunday a month. A museum is devoted to artifacts of traditional village life—antique dolls, rocking horses, family photographs, crockery, lobsterfishing implements, carpentry tools. "Even more than an island or hometown, Long Island is a family and heritage," Dean wrote in his memoir. "I am unapologetically proud to say my family built the island community and has helped sustain it for more than 180 years." But for all the love of tradition, he insists, no one misses the low-tech days of yore, when lobstermen lost their buoys and their bearings in the fog and spent winters repairing wooden traps, now made of wire. "Fiberglass boats," he adds, "require a lot less maintenance—no more scraping hulls and repainting wood boats. A lobster fisherman's life is never easy, but it has gotten better."

The next day, back on the mainland, I drive to Cape Rosier along the western coast of Blue Hill Peninsula and to Four Season Farm. Renowned internationally as a center for innovative organic agriculture, it's celebrated locally for its vegetables. On this sunny morning, several young men and women—paid apprentices studying organic farming, I later learn—are hoeing and raking rectangular beds after a recent harvest of cabbage and lettuce. At a nearby plot, Eliot Coleman, Four Season's 69-year-old founder and famed organic-farming guru, is on his knees, preparing a pea and broccoli patch for fall spinach.

Despite Maine's short growing season—no more than four or five months—Coleman and his wife, Barbara Damrosch, the farm-and-gardening columnist for the Washington Post, coax two, sometimes three, harvests from their land. No pesticides or chemical fertilizers are applied. Yet these one-and-a-half acres—including a quarter-acre greenhouse used during winter—produce 35 organically grown vegetables that grossed $120,000 in sales last year. "I doubt there is a chemical farm for vegetables that comes close to our yields," says Coleman. "So anybody who tells you that organic farming can't feed the world is just plain ignorant."

Coleman, by his own admission, stumbled across his true calling. After a suburban childhood in Rumson, New Jersey, he became a self-described "ski bum." After winter in the United States and Europe, he would head to Chile, where the Andes are covered in snow from June to September. "At some point in my mid-20s," Coleman says, "I thought there ought to be something more socially redeeming than racing down the next mountain." In 1967, he read Living the Good Life, originally published in 1954, by Helen and Scott Nearing, early leaders of the back-to-the-land movement of the late 1960s. "Just weeks later, I traveled to Maine to meet Scott Nearing," says Coleman. Nearing sold Coleman, then 28, a 40-acre piece of land for $33 an acre—what the Nearings had paid for it in 1952. "Nearing didn't believe in making profit from unearned income," says Coleman.

The quality of Coleman's vegetables gained him customers—and eventually the same kind of following that the Nearings had once inspired—throughout the Acadia region. Each year, Four Season hires and boards five or six aspiring farmers. "Coleman teaches us to view vegetables as a litmus test of how good a soil we have created," says Jeremy Oldfield, 25, from Washington, D.C., as he readies a spinach plot.

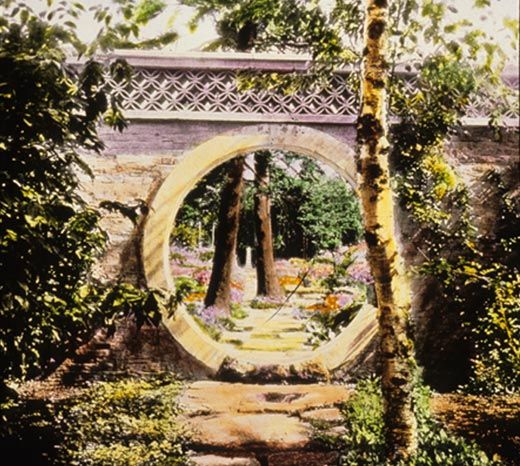

Damrosch, for her part, cites Beatrix Farrand as one of her greatest influences. In the 1920s, Farrand designed a garden for Abby Aldrich Rockefeller and her husband, John D. Rockefeller Jr., at Seal Harbor (pop. 309) on Mount Desert Island. Damrosch recalls sneaking into the private garden during the early 1960s, when she worked at a nearby inn during a summer break from college. "The garden was beautifully maintained," recalls Damrosch, sounding somewhat chagrined about trespassing. "I had never seen a garden so grand," she continues, "the Chinese-style wall, the statues, the blending of flowers with native plants and ground covers. Yet Farrand achieved a sense of intimacy by designing the garden into small spaces, each with its own character."

Today, the Rockefeller Garden can be visited only by appointment, though the Rockefeller family has announced plans to open it to the public eventually, connecting it by woodland trail to two nearby public gardens associated with Farrand—the Asticou Azalea Garden and Thuya Garden. Charles Savage, a local innkeeper and self-taught landscape designer, created both gardens in the 1950s, using relocated plants that Farrand had tended at Reef Point, once her garden and home in Bar Harbor.

Asticou, with its azaleas and rhododendrons, had peaked in spring, so I stopped instead at Thuya, in full summer bloom, climbing a trail under the white cedars (Thuja occidentalis) that give it its name. The garden is riotous with color—day lilies, delphiniums, snapdragons, a dozen other flowers. In the distance, sailboats scud across Northeast Harbor on a breezy, sunlit day.

Why Farrand's Reef Point garden no longer exists remains a subject of conjecture. Nearing retirement in the 1950s, Farrand, then in her 80s, expressed the hope that the town of Bar Harbor would help maintain it as a public attraction and horticultural research center. Though the 1947 fire had sharply depleted Bar Harbor's treasury, Farrand was well-connected both by birth—her aunt was the novelist Edith Wharton—and by wealthy clients, including the Rockefellers and the Morgans. She likely could have found a patron to fund Reef Point.

Locals suggest that Farrand, a legendary perfectionist, was unwilling to entrust Reef Point to others to manage after her death. Patrick Chassé, a noted landscape architect and Mount Desert Island resident, buys into this theory. "She really couldn't bring herself to give up control over the garden, so in 1955, she decided to disperse her plants," he speculates.

Many of the Reef Point plants ended up at Asticou and Thuya. Farrand had the remainder moved to Garland Farm, eight miles northwest of Bar Harbor, where she lived from 1956 until her death three years later at age 86. Today, as a result of fundraising and design work by Chassé and others, the five-acre Garland Farm Gardens, though under restoration, is open to the public by appointment.

The revival of Garland Farm serves as a reminder of the conservationist ethic celebrated throughout this region. Surely George Dorr, Acadia National Park's primary founder, would have applauded this most recent preservation effort. As he admonished in 1942: "I trust it will be recognized that what we have now achieved is a beginning only."

Writer Jonathan Kandell lives in New York City.

Photographer Brad Dececco is based in Brooklyn, New York.