A Journey to Obama’s Kenya

The dusty village where Barack Obama’s father was raised had high hopes after his son was elected president. What has happened since then?

The new asphalt highway to Barack Obama’s ancestral village winds past maize fields and thatched-roof mud huts for several miles before terminating at a startling sight: a row of lime-green cottages with pink pagoda-style roofs, flanked by two whitewashed, four-story villas. Kogelo Village Resort, a 40-bed hotel and conference center that opened last November, is the latest manifestation of the worldwide fascination with the U.S. president’s Kenyan roots. Owner Nicholas Rajula, a big man with a booming voice, was sitting beneath a canopy on the parched front lawn answering a pair of cellphones when I drove through the gate. Rajula stirred controversy here in 2007, shortly after he helped organize a tour of western Kenya for the junior senator from Illinois. Calling himself a distant cousin, Rajula ran for a seat in the Kenyan Parliament. Obama’s campaign officials disputed his family connections, and Rajula lost the election.

Now, five years later, the Kenyan entrepreneur is back in the Obama business. “I visited Barack three times in Washington when he was a U.S. senator,” said Rajula, a textbook distributor who built his hotel, as his brochure boasts, “only 200 meters away from Mama Sarah Obama’s home” (a reference to the president’s step-grandmother). Furthermore, Rajula claimed, “Barack inspired me. We were alone in the lift, in the U.S. Capitol, and he patted my back and said, ‘Cousin, I am proud of you. You are a businessman.’” Most members of the local Luo tribe, Rajula asserted, are “lazy people, not good at business. I told myself that should Barack come back to Kogelo, he will find the Luo businessman that he met in D.C. and see that he owns this magnificent hotel.”

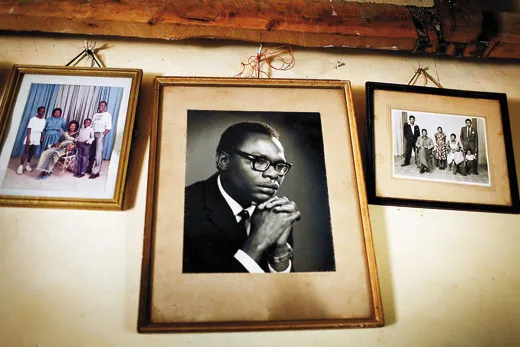

Nyang’oma Kogelo first came to public attention in Barack Obama’s Dreams From My Father, his acclaimed autobiography published in 1995. The story is largely about young Obama’s search for the truth about his brilliant but self-destructive father. A Kenyan exchange student who met the future president’s mother, Ann Dunham, at the University of Hawaii in 1960, Barack Sr. abandoned the family when his son was 2, returned to Kenya and went on to a career as a government economist. After falling into alcoholism and poverty, he died in a car crash in Nairobi in 1982, at age 46. “He had almost succeeded, in a way his own father could never have hoped for,” writes the son he left behind in America, toward the end of Dreams From My Father. “And then, after seeming to travel so far, to discover that he had not escaped at all!”

Five years after his father’s death, the younger Obama flew to Nairobi and embarked on an emotional trip to the family homestead in Nyang’oma Kogelo. “I remember the rustle of corn leaves, the concentration on my uncles’ faces, the smell of our sweat as we mended a hole in the fence bounding the western line of the property,” he writes. “It wasn’t simply joy that I felt in each of these moments. Rather, it was a sense that everything I was doing, every touch and breath and word, carried the full weight of my life, that a circle was beginning to close.”

Tourists—especially Americans—have followed Obama’s footsteps to this once-obscure rural community a half-hour north of Lake Victoria ever since. After Obama’s 2008 victory, many Kenyan tour operators added side trips to Nyang’oma Kogelo. These tours typically promise an opportunity to meet Obama’s relatives, visit the market, gaze at the fields and house where Barack Sr. spent much of his childhood, and ponder the president’s uniquely cross-cultural identity. Nyang’oma Kogelo is also at the center of a push to invigorate what is optimistically known as the Western Kenya Tourism Circuit: little-visited but beautiful highlands that include Lake Victoria, the lakeside railroad city of Kisumu, bird sanctuaries and sites where legendary paleontologists Mary and Louis Leakey made some of their landmark discoveries about the origins of mankind. Locals continue to hope that investment will flow into this long-neglected region. Here, the HIV-AIDS infection rate is among the highest in the country and unemployment, boredom and poverty drive young people to migrate to the urban slums in search of opportunity. So far, however, the global attention paid to Nyang’oma Kogelo has proved a boon to only a few enterprising insiders like Rajula. For the rest, the initial wave of excitement has dimmed, replaced by disappointing reality.

In Dreams from My Father, Barack Obama begins his journey west by train from Nairobi to Kisumu. He notes from his window “the curve of the tracks behind us, a line of track that had helped usher in Kenya’s colonial history.” Kisumu was founded in 1901, at the terminus of the Uganda Railway, which ran for 600 miles from Mombasa to the shores of Lake Victoria. It set forth a wave of white colonial migration deep into the East African interior that would soon touch the life of Hussein Onyango, Barack’s grandfather. Born in 1895 in Kendu Bay on Lake Victoria, Onyango moved as a young man back to the ancestral lands of Nyang’oma Kogelo. Onyango both respected and resented the white man’s power. He worked as a cook for British families, served with the King’s African Rifles during the First and Second world wars, and was jailed for six months in 1949, charged with membership in an anti-colonial political organization. The migration would also affect the fate of Barack Obama Sr.—the bright schoolboy dabbled in anti-colonial politics following his father’s detention, then pursued a Western education in the hope of transforming his fragile, emerging nation, which would achieve independence in 1963.

Kisumu is a sleepy provincial city that sprawls along the eastern shore of Lake Victoria. As I journeyed by rented 4 x 4 from there, deeper into the Kenyan countryside, I encountered all the signs of rural poverty that the young Obama had noted on the same route. Here were the “shoeless children,” the “stray dogs [snapping] at each other in the dust,” the “occasional cinder- block house soon replaced by mud huts with thatched, conical roofs.” Then I crossed a chocolate-colored river and at a crossroads reached Nyang’oma Kogelo.

The market, a typical African bazaar, consisted of rickety stalls surrounded by shabby shops selling T-shirts and tins of condensed milk. A drive down a red-earth road, past groves of bananas and rolling hills covered with plots of millet and maize, brought me to the homestead of Malik Obama. Born Roy Obama in 1958, he is the president’s half-brother and the oldest son of Barack Obama Sr., who had eight children with four wives. He has invested a large sum in the soon-to-open Barack H. Obama Recreation Center and Rest Area in Nyang’oma Kogelo. Obama has also developed a reputation as something of an operator. When, en route to Nyang’oma Kogelo, I inquired about the possibility of an interview, he texted back: “My schedule is brutal but I might/could squeeze you in for about thirty minutes if I can get $1,500 for my trouble.” I politely declined.

Mama Sarah Obama, the widow of Barack’s grandfather, lives in a tin-roofed house set back a few hundred yards from the road. After the inauguration, Mama Sarah was besieged by well-wishers, greeting dozens of strangers a day. “She is a very social, very jovial person,” a friendly police officer at her front gate told me. The strangers included those with more nefarious purposes, such as members of the U.S. “birther” movement, who hoped to gather “proof” that the president was born in Kenya.

After the killing of Osama bin Laden last year, the Kenyan government heightened security around Mama Sarah’s compound. Even so, she still meets visitors. When I phoned her daughter from the gate, I was told that her mother was resting, but that I should come back in several hours. Unfortunately, my timing was not fortuitous. Mama Sarah, 91, was recovering from minor injuries suffered two days earlier when the car she’d been riding in overturned on the way back from Kendu Bay, near Lake Victoria. She wasn’t up for greeting me today, a plainclothes security man told me when I returned.

Between August 2008 and January 2009, hundreds of journalists from around the world descended on Nyang’oma Kogelo. “People got so excited,” I had been told by Auma Obama, the president’s half-sister (the daughter of Barack Obama Sr. and his first wife, Kezia) when we met in a Chinese restaurant in Nairobi the evening before my trip west. Auma, 52, studied German at the University of Heidelberg and earned a PhD at Germany’s University of Bayreuth. She then lived for a decade in London before resettling, with her daughter, in Nairobi in 2007. She is now a senior adviser to CARE International in Nairobi and started a foundation that, among other projects, teaches farming skills to teenagers in Nyang’oma Kogelo. Reticent about discussing her relationship with her half-brother, Auma is voluble about Nyang’oma Kogelo’s roller-coaster ride leading up to and during the Obama presidency. “People there had the feeling that ‘they were the chosen people,’” she told me. But the attention, she says, was “distracting and deceiving. It was like a soap bubble.”

A flurry of changes did improve the lives of some members of the community. Eager to showcase Nyang’oma Kogelo’s connection to the president, the government built a tarmac road, now two-thirds finished. The government also strung power lines to shops in the village center and to several families, dug a borehole and lay water pipes both to Mama Sarah Obama’s homestead and the Nyang’oma market. The flow of tour buses into Nyang’oma Kogelo has pumped a modest amount of cash into the local economy.

Other hoped-for improvements have not materialized. For several years, the government has promised to construct a million-dollar Kogelo Cultural Center. Today, the large plot of pastureland on the edge of town, donated by a local resident, stands empty.

Before Barack Obama visited the secondary school in 2006, the local council renamed the school in his honor. Many believed that the concrete buildings and scruffy fields would soon get a face-lift—possibly from Obama. It did not happen. “I tell them, of course, he is the U.S. president, not ours,” says geography teacher Dalmas Raloo. We’re sitting in a tin-roofed shelter built last year by an American tourist, after she noticed that students were eating lunch fully exposed beneath the broiling equatorial sun. The village’s unrealistic expectations, Raloo believes, reflect the passive mentality of people who have always “relied on grants and donations to get by.”

Raloo is working with Auma Obama to change that way of thinking. Obama’s two-year-old foundation, Sauti Kuu, Swahili for Powerful Voices, aspires to break the cycle of rural dependency and poverty by turning youths into small-scale commercial farmers. The program—in its pilot phase—identifies motivated kids between 13 and 19, persuades parents to turn over fallow land, then works with experts to grow crops to generate money for school fees. “Before, people believed in handouts,” says field supervisor Joshua Dan Odour, who has helped several teenagers bring their tomatoes to the local market. “We’re trying to introduce the concept that you can do much better things.” Obama says the kids understand her message: “You need to use the resources you have in order to succeed.”

Barack Obama glimpsed Lake Victoria on the drive from Nyang’oma Kogelo to meet the other branch of his family in Kendu Bay. In Dreams From My Father, he describes its “still silver waters tapering off into flat green marsh.” The largest lake in Africa and second-largest in the world, after Lake Superior, 27,000-square-mile Lake Victoria was formed about half a million years ago, in one of the periodic tectonic convulsions of the Great Rift Valley. It received its regal name from the British explorer John Hanning Speke, who reached its shores in 1858.

I had decided to stay at one of Lake Victoria’s most renowned tourist destinations. A 20-minute crossing from the mainland in a car ferry brought me to Rusinga Island, flat and gourd-shaped, nine miles long and five miles wide. The island has a population of 25,000 subsistence farmers and fishermen from the Suba tribe. We followed a dirt track past maize fields to the Rusinga Island Lodge, the former home of a British Kenyan family, converted into a luxury resort a quarter of a century ago. A dozen elegant, thatched-roof cottages were scattered amid palm, eucalyptus and mango trees. Pied kingfishers and other brightly colored avian species darted among the foliage. The garden sloped toward Lake Victoria, which sparkled beneath a searing sun.

After the heat had subsided in the late afternoon, I climbed into a launch, then motored out to explore the nearby islands. The boatman and guide, Semekiah Otuga, a Suba, identified a classical white marble structure looming above the cornfields as the mausoleum of Tom Mboya. A prominent Luo politician at the time of Kenya’s independence, he was widely seen as a likely successor to Jomo Kenyatta, the country’s first president. Mboya created a scholarship program in the late 1950s, enabling gifted Kenyans to attend universities abroad; among its beneficiaries was an ambitious young student of economics named Barack Obama Sr., who would become the first African exchange student at the University of Hawaii at Manoa in Honolulu. In 1969, possibly as the result of a plot organized by his political rivals, Mboya was shot dead in downtown Nairobi.

Otuga steered toward Takawiri Island, one of 3,000 islands strewn across Lake Victoria. We beached the craft on a strip of white sand framed by coconut palms. Tucked behind the palms were a dozen cobwebbed cabins from a business venture gone awry: the Takawiri Island Resort. Envisioned by its owners as a magnet for Lake Victoria tourism, the hotel suffered from a lack of visitors and was forced to close in 2003.

Just beyond Takawiri, we anchored between two chunks of black rock known as the Bird Islands. Thousands of long-tailed cormorants, attracted by schools of Nile perch and tilapia, roosted in the island’s fig trees and dead white oaks—a vision from Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds come to life. We drank Tusker beers in the fading light, and then, beneath a near-full moon, Otuga started up the engines and sped back to Rusinga.

During my last morning on Rusinga, Otuga led me up a sunbaked slope, known as Kiahera, above Lake Victoria. Beginning in the 1930s, Mary and Louis Leakey combed sites on Rusinga, searching for Miocene era fossils; during that period, between 18 million and 20 million years ago, a volcano near Lake Victoria had erupted and preserved the island’s animals and plants, Pompeii-like, beneath a layer of ash. On October 1, 1948, Mary made one of their most important discoveries. “I was shouting for Louis as loud as I could, and he was coming, running,” she recalled in her autobiography. She had glimpsed what biographer Virginia Morell describes in Ancestral Passions as “a glint of a tooth” on Kiahera’s eroded surface.

Using a dental pick, Mary Leakey chipped away at the hillside, gradually revealing a fragmented skull, as well as two jaws with a complete set of teeth. “This was a wildly exciting find,” Mary Leakey wrote, “for the size and shape of a hominid skull of this age so vital to evolutionary studies could hitherto only be guessed at.” The young paleontologist had uncovered an 18-million-year-old skull of a hominid, “remarkably human in contour,” the first persuasive evidence of human ancestors in Africa in the Miocene. Louis Leakey cabled a colleague in Nairobi that “we [have] got the best primate find of our lifetime.”

Otuga pulls out a ceramic replica of the Leakeys’ find. Western tourists, he says, have been moved by the historic importance of Kiahera—with the exception of an American pastor whom Otuga escorted here, with his family, last year. The churchman looked displeased by Otuga’s foray into evolutionary science and “told me that I was a bad influence on the kids,” Otuga says. “I was wondering why he came up here in the first place.” It is another indication that even here, in this remote and beautiful corner of East Africa, the culture wars that roil America are keenly observed, and felt.

Otuga led me back down the hillside. I stood at the edge of the lawn of Rusinga Island Lodge, taking in my last views of Lake Victoria. In 1948, while the Leakeys were pursuing their paleontological quest, Barack Obama Sr. was a schoolboy in the Luo highlands, not far from here, driven in part by his anger at white colonial privilege to educate himself and help reform the new nation of Kenya. Six decades later, as I’ve been reminded by my journey through the Luo highlands, this remains in many ways a deeply divided country. The divide is no longer so much between black and white, but between the privileged, well-connected few and the destitute many. Call them Kenya’s 99 percent. Barack Obama’s presidency in far-off America filled many ordinary Kenyans with unrealistic expectations, persuading them that their lives would be altered overnight. It has been left to dedicated realists like his sister Auma to bring them down to earth—and to convince them that transformation lies in their own hands.

Guillaume Bonn travels on assignment from Nairobi.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)