“Word, Shout, Song” Opens at the Anacostia Community Museum

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20110520110606Ring-Shouters-Georgia.jpg)

In 1930, Lorenzo Dow Turner, an English professor-turned linguist, began studying a language spoken by former slaves along the east coast of South Carolina. Words spoken there, like gambo, tabi and jiga, would reveal a complex web of linguistic and cultural convergences between the Gullah people and the African countries, former homelands to the 645,000 enslaved Africans transported to the United States between the 16th and 19th centuries.

Turner was introduced to Gullah while teaching at an agricultural and mechanical college in South Carolina in 1930. While others had dismissed the dialect as "bad English," the language, Turner would discover, arose from a hybrid of 32 different African languages.

A landmark figure in forging a path for the advancement of African Americans in the world of academe, Turner's work and continuing legacy are featured in Word Shout Song: Lorenzo Dow Turner Connecting Communities Through Language, a new exhibit at the Anacostia Community Museum that will run through March, 2011.

Turner was "a pioneer in establishing black studies programs," said the show's curator Alcione Amos. Born in North Carolina in 1890, Turner was a gifted student and athlete, attending Howard University before receiving his master's degree from Harvard in 1917. He became one of the first 40 African Americans to obtain a doctorate degree, and the first African American professor to be appointed in 1946 to a teaching position outside of a black college.

But amidst his unprecedented success, Turner's interests remained with the Gullah people he'd met in South Carolina. Their language seemed at once foreign and familiar, and held for him an irresistible pull. He began studying linguistics and conducting preliminary research into Gullah, recording the speech of people he met, photographing them, and learning the African languages—Ewe, Efik, Ga, Twi, Yoruba and later Arabic—that he suspected might be the root influences to the Gullah words.

"The resemblance between these languages and Gullah much more striking than I had supposed," he wrote to the president of Fisk University in 1936.

The words had an undeniable similarity. The words for okra, in Gullah "gambo" and "kingombo" in Kimbundu, a language spoken in Angola, later became gumbo in English. The Gullah word "tabi," meaning the cement made from oyster shells (later tabby in English) resembled the word, "tabax," or stone wall, in the sub-Saharan Wolof language. And the word for insect, jiga, in both Gullah and the West African Yoruba language, became in English jigger, meaning mite.

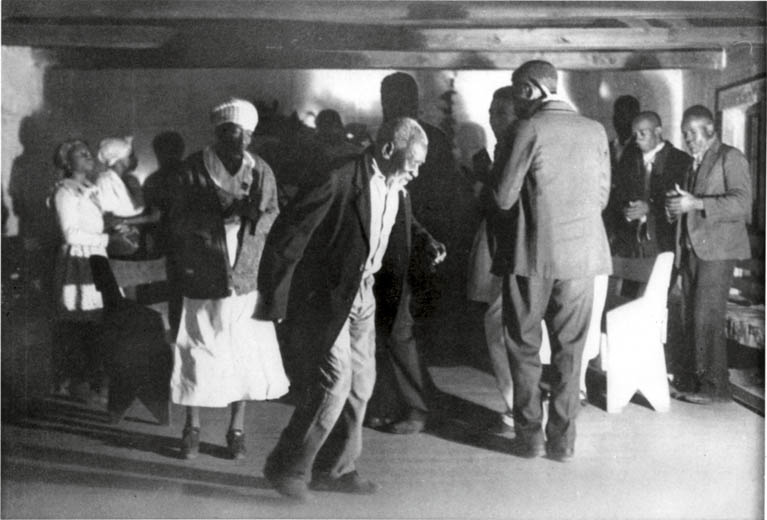

It soon became apparent to Turner that deeper cultural ties were also maintained. He discovered that the "ring shout," a circular religious dance and song performed by Gullah people on the Sea Islands, was similar to African circular religious rituals.

Alcione Amos sees the survival of these many African languages in Gullah as a testament to the fortitude of those who have perpetuated them. "It's the strength of the people brought here as slaves," she said. "They couldn't carry anything personal, but they could carry their language. They thought everything was destroyed in the passage. But you can't destroy peoples' souls."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jess-righthand-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jess-righthand-240.jpg)