“Somebody had to do it,” says Lt. Col. Alexander Jefferson, a 99-year-old member of the renowned Tuskegee Airmen. As the first Black pilots in U.S. military service, the Airmen's bravery both in the air and in enduring racism made them legends and the personification of honor and service.

“We had to rise to the occasion,” recalls Jefferson, a proud member of the 332nd Fighter Group and one of the class of pilots known as “Red Tails” after the distinctive markings on the P-51 Mustangs that they flew. On missions deep into enemy territory, including Germany, they escorted heavy bombers to their targets. “Would we do it again? Hell yes! Would we try doubly? You’d better believe it. Did we have a lot of fun? At gut level, it was great!”

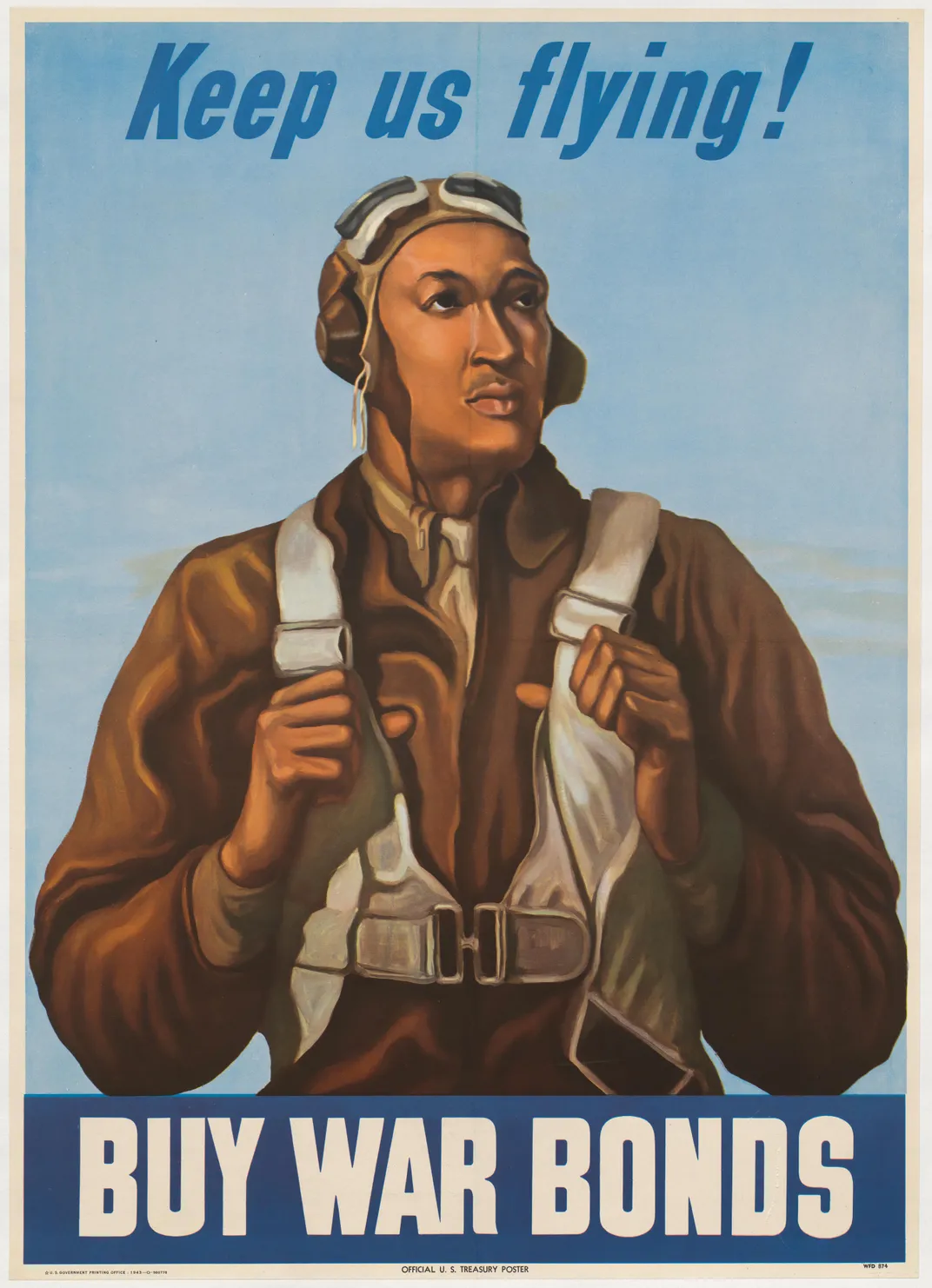

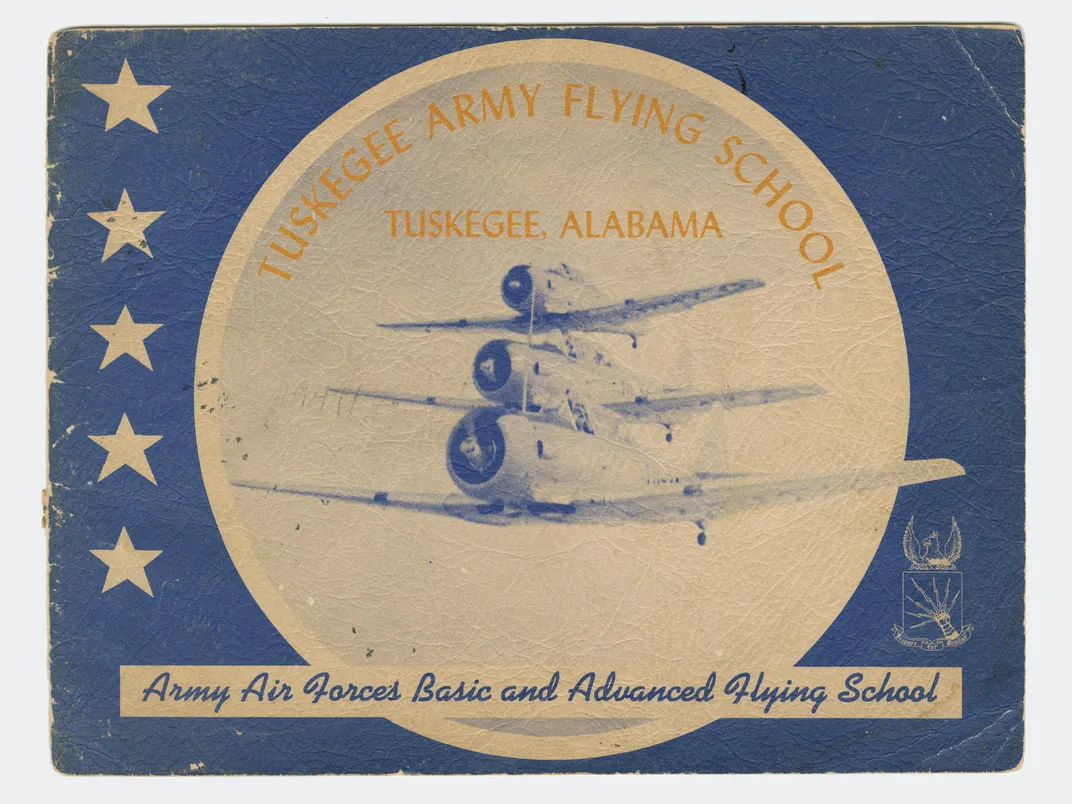

This week, March 22, marks the 80th anniversary of the activation at Chanute Field, Illinois, of the first Black flying unit, the 99th Pursuit Squadron. Later known as the 99th Fighter Squadron, it moved to Alabama's Tuskegee Army Airfield in November 1941. The first Black pilots graduated from advanced training there in March 1942. Eventually, nearly 1,000 Black pilots and more than 13,500 others including women, armorers, bombardiers, navigators and engineers in various Army Air Force organizations who served with them, were included in what is known by Tuskegee Airmen, Inc. as the “Tuskegee Experience” from 1941 to 1949.

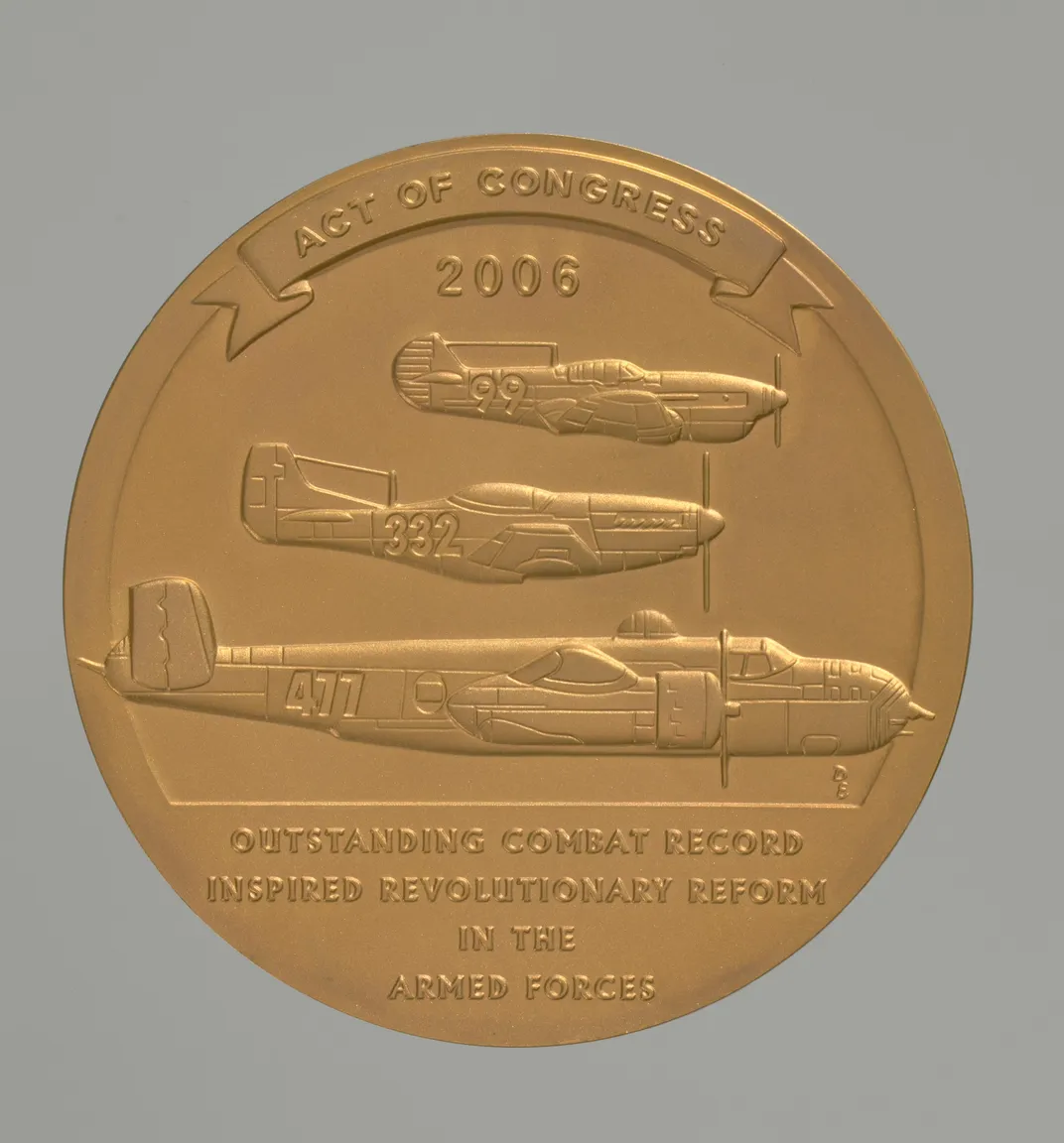

The Tuskegee Airmen flew more than 15,000 individual sorties in Europe and North Africa during World War II and earned 96 Distinguished Flying Crosses. Their prowess, in a military establishment that believed that black Americans were inferior to white Americans and could not possibly become pilots, became what many see as the catalyst to the eventual desegregation of all military services by President Harry S. Truman in 1948. Facilities around the country, including the Tuskegee Airmen National Museum in Detroit, have a plethora of artifacts dedicated to telling their story. In Washington, D.C., the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) has an aircraft known as the “Spirit of Tuskegee” hanging from the ceiling. The blue and yellow Stearman PT 13-D was used to train Black pilots from 1944 to 1946.

Lt. Col. Jefferson didn’t train on that aircraft, but he got to take a ride in it in 2011, before it arrived at Andrews Air Force Base. The plane was bought and restored by Air Force Captain Matt Quy, who flew it across the country to donate it to the museum. The training aircraft made several stops at air shows and airfields across the nation, including its original home at Moton Field during World War II, in Tuskegee, Alabama. Quy flew the “Spirit of Tuskegee” that year over a hotel at Maryland's National Harbor, during a Tuskegee Airmen convention. Forty of the original airmen and hundreds of other members of the legendary group were on hand, celebrating the 70th anniversary of their first training missions.

“It was fantastic,” Jefferson recalls, adding that it reminded him of a similar aircraft on which he learned to fly. “It brought back memories of my first ride in a PT-17 .”

Smithsonian curator Paul Gardullo, who says collecting the Stearman PT-13 was possibly one of the most momentous things he helped accomplish for NMAAHC, also got to take a ride in the open cockpit biplane. He notes it is one of a host of aircraft used by the Tuskegee Airmen that do not have red tails like the famous P-51s.

“When you take off, you don’t necessarily feel that strong thrust like you do in a typical 747. It’s slow, it’s easy, and because it’s open, you feel like you are part of nature. You feel everything around you,” Gardullo says. “What it provides is this incredible sense of your connection to that machine because it is so small, your connection to the world around you and your ability to control your destiny. That’s what I think is such an empowering thing when I think about these men who are learning to fly for the first time, and that’s what they talk about.”

Gardullo says the P-51 is a deeply important and symbolic plane, especially the red tail. But he says when he spoke with some of the Tuskegee Airmen who saw the training plane as it made its journey across the nation, particularly at its stop in July 2011 in Tuskegee, he got an evocative, incredible history lesson.

“We learned about the trials that they went through, not just the technical trials of learning how to fly a plane, but learning how to fly a plane in the Jim Crow South, and what it meant to hold a position of esteem and authority, and demonstrate your patriotism in a country that isn’t respecting you as a full citizen,” Gardullo explains. “That brought us face to face with what I call a complex kind of patriotism. And there’s no better example of that than the Tuskegee Airmen, the way in which they held themselves to a standard higher than the nation held them in esteem. It’s a powerful lesson, and its one we can’t ever forget when we’re thinking about what America is, and what America means.”

The Smithsonian’s Spencer Crew, who most recently held the position of NMAAHC’s interim director, notes that the history of the Tuskegee Airmen is remarkable, and that their battle goes all of the way back to World War I, when Black Americans lobbied the federal government to participate in the war as airmen, and to fight aerial battles. At that time, because of segregation, and the belief that Black people could not learn to fly sophisticated aircraft, they weren’t allowed to participate. In 1938, President Franklin D. Roosevelt announced that the U.S. Army Air Corps (AAC), a precursor of the U.S. Air Force, would expand its civilian pilot training program. Then the NAACP and Black newspapers such as the Chicago Defender and the Pittsburgh Courier began lobbying for African American inclusion.

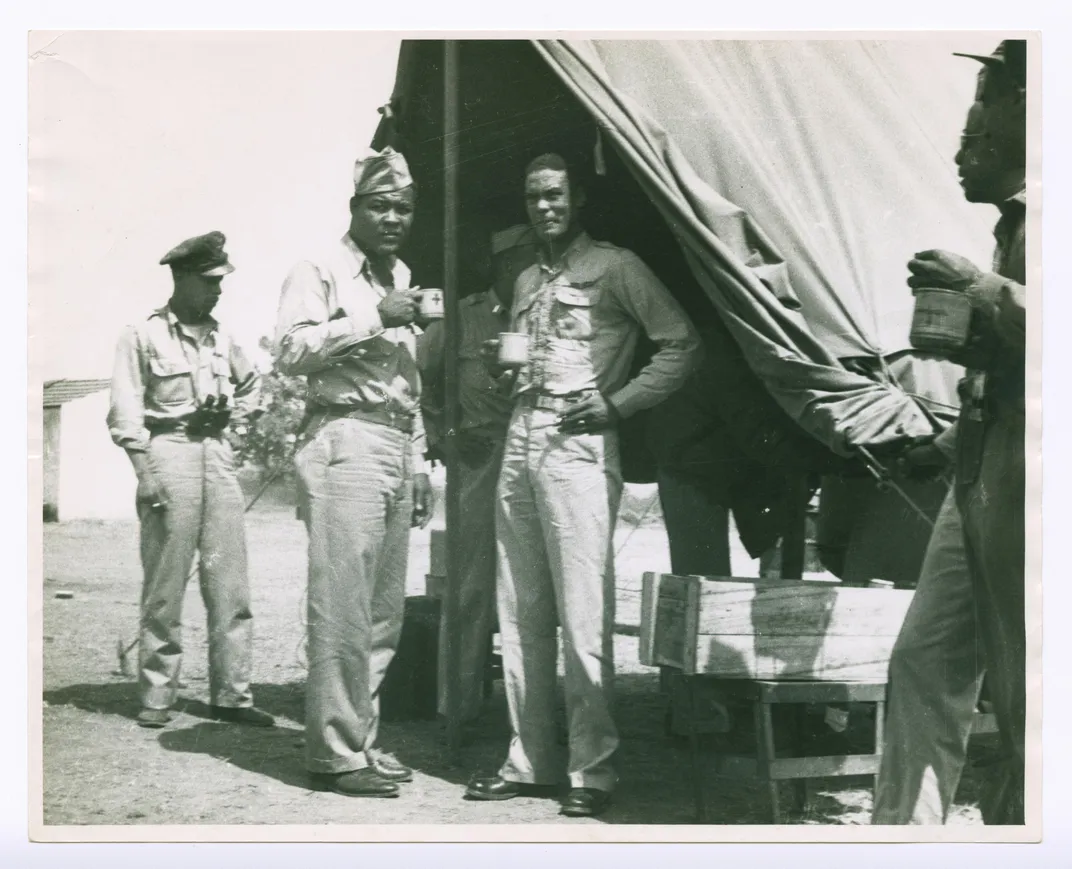

“What happened is that Congress finally puts pressure on the War Department to allow African Americans to train to be pilots, and the War Department figures they don’t have the skills, the abilities or bravery to be airmen. They think, ‘What we’ll do is send them to Alabama and attempt to train them, but we expect that they will fail,’” Crew explains. “But instead, what happened is that these really, brilliant men go to Tuskegee, dedicate themselves to learn how to fly and become a very important part of the Air Force. They were highly trained when they got to Tuskegee in the first place. Some had been trained in the military, many had been engineers, and they just brought a very high skill level with them to this work.”

A look at a few of their resumes, before and after being Tuskegee Airmen, is stunning. General Benjamin O. Davis Jr., part of the first class of aviation cadets, was a graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, who commanded both the 99th Fighter Squadron and the 332ndd Fighter Group, and became the first Black general in the Air Force. He is the son of General Benjamin O. Davis Sr., the first Black American to hold the rank in the U.S. Army. General Daniel “Chappie” James, who served in the 477thBombardment Group, flew fighter aircraft in the Korean and Vietnam wars, and became the first African American four-star general in the Air Force. Brigadier General Charles McGee, who served with the 332nd Fighter Group in World War II, also served in Korea and Vietnam, and flew 409 combat missions. Lt. Col. Jefferson, also with the 332nd Fighter Group, is the grandson of Rev. William Jefferson White, one of the founders of what is now Morehouse College in Atlanta. Jefferson worked as an analytical chemist before becoming a Tuskegee Airmen. He was shot down and captured on August 12, 1944, after flying 18 missions for the 332nd, and spent eight months in the POW camp at Stalag Luft III before being freed. He received the Purple Heart in 2001.

Jefferson, who will turn 100 years old in November, says the 80th anniversary of the beginning of the Tuskegee Airmen training program is very close to his heart, partly because there are so few of them left. He remembers what it felt like to begin the flying courses at the small airfield there, learning the craft from Black instructors. He says one had to volunteer for flight training, because even though African Americans were subject to the draft in the segregated military, that would not get you into the flying program.

“If you were drafted as a Black man, you went into a work situation where you were a private in a segregated unit doing nasty, dirty work with a white commander,” he remembers, adding that it was exciting to be breaking the rules society at the time had set up for African Americans. As an airman, one was an officer under better conditions, with better pay and a sense of pride and accomplishment.

“It was a situation where you knew you were breaking rules, but you were making progress, breaking ground,” Jefferson says. “We knew that we would be relegated to a segregated group, the 332nd Fighter Group, under the racial attitude of the government and we were fighting that too.”

He says he and the other Tuskegee Airmen think sometimes about how their achievements, in the face of deep racism, helped pave the way for other Black pilots.

“Here we were, in a racist society, joining up to fight the Germans, another white racist society, and we’re right in the middle,” Jefferson says, adding “we tried to do our job for the United States.”

Historian and educator John W. McCaskill gives lectures and does reenactments of military history including World War II and the Tuskegee Airmen, and has been helping to tell their story for decades. He wears their period attire, and his “History Alive” presentations sometimes involve one of the Red Tail planes. McCaskill helped get recognition for Sgt. Amelia Jones, one of the many women who worked in support capacity for the Tuskegee Airmen, under then Col. Davis Jr. with the then 99th Pursuit Squadron.

“It wasn’t just the pilots. It was anybody who was part of the Tuskegee Experience,” explains McCaskill, who met Jones in 2014 at the World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C., as part of the “Living History Meets Honor Flight” program. Once she told him she had been with the 99th, and sent her discharge papers, McCaskill and others were able to get her into Tuskegee Airmen Inc., and got her sponsored for a Congressional Gold Medal. It was awarded collectively to the Tuskegee Airmen in 2007.

“As a sergeant, she had about 120 women that she was in charge of, and they were dealing with mail, sending mail overseas,” McCaskill explains.

He says as the nation honors the service of the Tuskegee Airmen, it is important for people to understand just how much service Black people have provided for the military, and for the stories of the African American experience in military history to continue to be told. It is critical, he says, on their 80th anniversary.

“African Americans played a critical role in World War II, and just about 2,000 Black Americans were on the shores of Normandy on D-Day. But if you look at the documentaries and newsreels you don’t see them,” McCaskill says. “What this 80th anniversary says to me is that there are still people 80 years later who don’t know about this story and it needs to get out. Every time we lose one of them, we’ve got to ask the question: ‘Have we learned everything from that individual that we were supposed to learn?’ We cannot allow this story to die because every Black pilot, male or female, that sits in a military cockpit or commercial cockpit, owes a debt of gratitude to these individuals who proved once and for all that Blacks were smart enough to fly, and that they were patriotic enough to serve the country.”

Back at the Smithsonian, Crew says the PT-13 training plane that hangs from the ceiling is a wonderful representation of the important kinds of contributions that African Americans have made.

“What it does is remind our younger visitors of the possibilities of what you can do if you just decide to put your mind to it, and if you don’t let others define what you can accomplish and who you are in society,” Crew says, adding that this is of great importance due to the current level of division in the nation.

Lt. Col. Jefferson also has a message for young people.

“Stay in school, and learn how to play the game,” Jefferson says. “Fight racism every time you can.”

Editor's Note 5/3/2021: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated that the Tuskegee Experience ended in 1946; it ended in 1949. The story also said that the Tuskegee Airmen earned more than 150 Distinguished Flying Crosses; they earned 96. The story has been edited to correct these facts.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f5/ae/f5ae3953-c39a-4fbd-a74b-434af49336da/longform_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4d/8b/4d8ba617-0ca1-491f-886a-326719454e7b/longform_desktop-1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)