What a Mark Rothko Painting Has in Common With a Ming Dynasty Dish

This one vibrant color, rich in symbolism, unites two works across five centuries

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/15/0f/150fbd36-c1a9-46d8-ba97-0fa5cab4f7bc/f20152v1web.jpg)

Imagine an exhibition with just two objects.

The subject of the show “Red: Ming Dynasty/Mark Rothko,” currently at the Smithsonian’s Sackler Gallery, is about a painting and a dish.

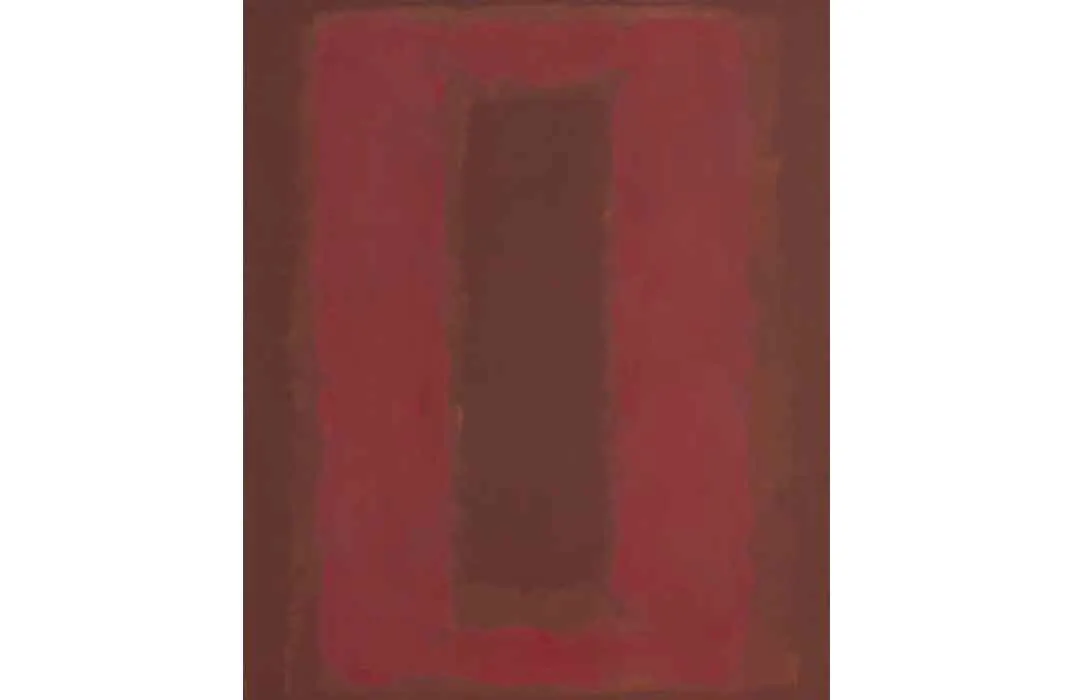

To demonstrate the power and levels of the chosen color of both objects—a rich, multi-layered red—the items are juxtaposed: An imperial Chinese porcelain dish from the Ming Dynasty and a Mark Rothko painting from 1959, Untitled (Seagram Mural Sketch).

The former, a rare artifact dating from the Xuande period of 1425 to 1436, is a new acquisition for the Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery; the latter a loan from the nearby National Gallery of Art.

Little is known, of course, of the artisans behind the plate, the first copper-red-glazed porcelain to become part of the permanent collection. But red was a color rich in symbolism for many cultures and particularly in China. The ritual ware, made for royalty, was rare in its monochrome approach, and yet within the red are fleeting bands of lighter burgundy, while at its edge, a pristine white band provides a contrast.

Rothko, too, was trying to create something around the borders of pictoral space with his more brooding approach to red. His darker tones contrast with brownish edges. Both works attempt to create an impact with nuanced clouds of color.

In Rothko’s case, however, there is a lot of his own writing available to explain his approach. One quote is writ large on the wall of the Sackler exhibition: “If you are moved by color relationships, you are missing the point. I am interested in expressing the big emotions—tragedy, ecstasy, doom.”

While Rothko’s aims were bold, exhibition curator Jan Stuart, the museum’s Melvin R. Seiden curator of Chinese Art, says, “the Ming potters had a different mindset—they were making a ritual ware for the emperor.

“And yet,” Stuart says, the artisans “worked with the same visual concerns—how to achieve an alchemy of color, texture, shape and edge. Rothko painted the edge of this canvas, while the Ming potters left the rim of the dish white to contrast with the red. In the end, the dish and painting together leave you weeping with the beauty of red.”

Rothko had more to say about his work, originally commissioned for the Four Seasons restaurant going up in the then-new Seagram Building designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson in New York City.

At the time it was the most prestigious public commission ever awarded an abstract expressionist painter—600 square feet of art that would have been a series of works for the high-end restaurant. Ultimately he turned down the $35,000 commission, returned his advance and kept the paintings. The works ended up at Washington's National Gallery of Art, at London’s Tate Gallery and in Japan’s Kawamura Memorial Museum.

Rothko’s thought process on the commission and his rejection of it, later became the basis of John Logan’s Tony Award-winning 2010 play Red, in which the doomed Rothko character says: “There is only one thing I fear in my life, my friend . . . One day the black will swallow the red.”

Indeed the palette for the series—much of which is in the Tate Gallery in London—got progressively darker with dark red on maroon leading to black on maroon, its shape suggesting open, rectangular window-like forms.

“After I had been at work for some time I realized that I was much influenced subconsciously by Michelangelo’s walls in the staircase room of the Medicean Library in Florence,” Rothko wrote.

Ultimately he kept his work out of the restaurant, because its appearance was more fitting to the “chapel” effect he was beginning to create with his clouds of paint communicating quietly to one another, as in a specially built site in Houston.

“The fact that people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures shows that I can communicate those basic human emotions,” Rothko said. “The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when painting them.”

So whatever did they have to do with the clatter, the cuisine and the high powered lunches of the Four Seasons anyway?

When it opened in 1959 at the Seagram Building on E. 52nd Street, the Four Seasons was celebrated as the most expensive restaurant ever built. It was the go-to spot for top celebrities and powerful CEOs, but a conflict with the building’s owner caused the architecturally-significant restaurant to shut down this past July 16. Its owners hope to reopen somewhere near the original site by summer 2017.

It’s fitting, then, that the “Red: Ming Dynasty/Mark Rothko” exhibition can also be seen as the result of a kind of displacement by similarly prominent buildings. The Freer, designed by architect Charles A. Platt, has been closed for renovations since early 2016 and won’t reopen until October 7, 2017; the galleries of the National Gallery’s I.M. Pei- designed East Wing had been closed for refurbishing since early 2014 before they recently reopened on September 30 of this year.

The resulting two-object exhibition offers a final irony as well: After bristling against the idea of his art appearing in a restaurant, Rothko’s Untitled (Seagrams Mural Sketch) ends up, despite any earlier protestations, right alongside a dish.

“Red: Ming Dynasty/Mark Rothko” continues through February 20, 2017 at the Smithsonian’s Sackler Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)