What Makes the Orange Juice Can Worthy of Display in a Museum

A new exhibition explains why the everyday objects of today and the recent past are so important to understanding who we are

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/33/b7/33b7c919-4eb1-4ec6-8933-3cea612a5249/et20152101web.jpg)

Visitors who stroll through the National Museum of American History’s exhibition “Object Project,” whose open floor plan is designed to encourage creative and individualized experiences of the “everyday things that changed everything,” would certainly be forgiven for missing a display of 13 frozen, orange juice concentrate cans atop a high shelf.

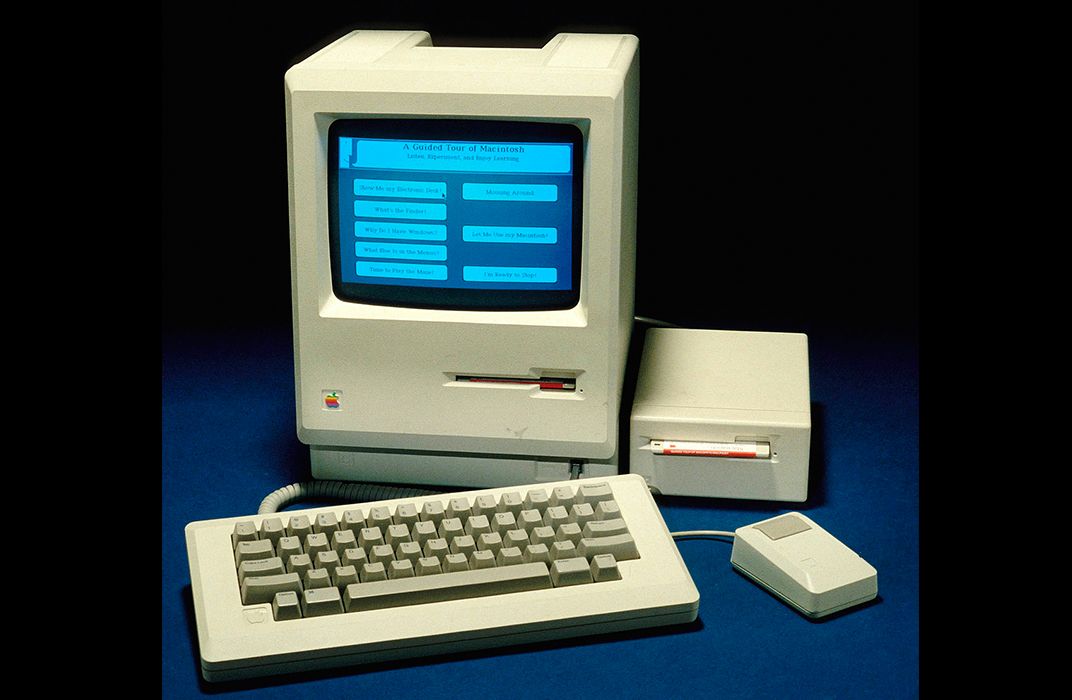

The exhibition, after all, contains what seem to be far more diverting treasures: a stunning 1919 cash register, an 1896 bicycle, early-model Apple computers, a 1900s Maytag washing machine, and a case with what looks like ten intricate sculptures but happen to be thermostats from the early 20th century.

The 250-plus objects in the show are organized by section, each emblematic of a broader social development: ready-to-wear clothes (“opportunity”), household hits (“transformation”), bicycles (“liberation”) and refrigerators (“happiness”).

The 60-year-old orange juice cans sport designs ranging from a winking Donald Duck to Minute Maid's former green and orange crown logo to a Whole Sun snowman with the head of an orange and carrying two armfuls of the fruit. But in a sea of more complicated and ambitious engineering feats, what’s so important about old cans of orange juice?

More than one might imagine.

“Introduced in 1946, frozen concentrated orange juice was quickly adopted by consumers who welcomed its time-saving convenience,” says Heather Paisley-Jones, a museum education specialist who purchased on eBay about 200 objects—ranging in price from a couple of bucks to a couple of hundred bucks. (The most expensive item? A fist-sized toy, Uncle Sam riding a bicycle, cost $500.)

Initially, museum staff members weren’t sure they would find any orange juice cans from the post-World War II era, but they knew they at least wanted a Snow Crop can to represent the first of this kind. “We ended up finding 17 different brands of orange juice containers, and they’re really quite beautiful objects,” Paisley-Jones says. The cans, which ranged in price from $2 to $30, often had scratches inside, probably from holding nails and screws. “I would imagine that’s where most of them spent their lives: in people’s garages,” she says.

Purchasing the cans and the other objects for the exhibition, Paisley-Jones, who collects vintage cameras, WWI artifacts and “tintypes of dogs and their humans” in her personal life, perfected her eBay skills in the past year and a half, during which a steady stream of boxes flowed into her mailbox. “It’s been Christmas for months,” she says.

Strategically, Paisley-Jones pored over countless photos of objects before purchasing them to ensure that they were in good condition and were in fact what sellers claimed them to be, and she used an anonymous eBay handle so that sellers only learned that she represented a museum after the purchase was complete.

“We want to make sure we are spending our money wisely and not have people mark things up,” she says. (She also checked in with Minute Maid, only to learn that it didn’t have any important, older cans in its collection; though the company got a kick out of being contacted, she adds.)

The orange juice cans of “Object Project” are exhibited behind glass, but other pieces in the show, including ice cube trays and a water bottle, which are similarly easy and cheap to purchase (and if necessary, repurchase) on eBay, are available for visitors to touch.

Asked if the museum is concerned that some visitors might mishandle the real objects, Judy Gradwohl, the museum’s associate director for education and public engagement, says museum staff will simply purchase new ones, if necessary.

“We have a commitment to keep authentic objects out here. These are manufactured objects,” she says. “Sharing airspace with objects is incredibly important. There are very good reasons for putting everything behind glass in a museum, especially one with the large number of visitors that we have and dusting issues. But there’s nothing quite like being able to heft things and try them out for yourself.”

Trying things out for oneself is a broader theme of the ready-made clothing section of the exhibition as well, which addresses, in part, how the clothing in question democratized fashion. “As an immigrant, you can take off a shawl and put on a hat and become an American. Or go to the bargain basement of a department store and dress like a gentleman. Or order up clothes out of the Sears catalog and look like a movie star,” Gradwohl says. “It sort of blurs class distinctions and helps democratize society.”

Looking at both how these innovative objects shaped everyday life and the social change that they ushered in and catalyzed is a major goal of the the new show, according to Gradwohl. Bicycles, for example, spelled liberation for women because it allowed them to venture further from home and at later hours in the day without chaperones. Bikes, Gradwohl says, were also instrumental in leading to the late 19th and early 20th-century Good Roads Movement, and, subsequently, the highway system.

“Bikes were hugely important in daily life, especially in small towns,” she says.

Elsewhere in the exhibit, viewers can see a painted portable window screen from 1888, which would have had to be carried around the house whenever one wanted to open a window. (Previously, even in the heat of summer, windows would have remained closed.) “It was incredibly important in protecting against disease and regulating some of your internal temperature,” Gradwohl says of the painted screen, whose design anticipates the works of the prolific artist Thomas Kinkade.

And at another station in the exhibition, viewers can learn about and touch the early ice cube trays, one of which has an elaborate contraption that helps remove the cubes from the tray. Previous ones required users to pour hot water over the tray and to then chip off the resulting cubes. Refrigerators and freezers, and the ice cubes they helped usher in, allowed people to safely eat leftovers for the first time.

“Ice cubes were really exciting,” Gradwohl says, noting how complicated the instruction booklet was for one of the trays. “You needed an advanced degree [to make them],” she adds with a laugh.

One highlight of the exhibit is the “Wheelwoman,” a living history performance, which is part of the museum’s “History Alive!” theatrical series. D.C. actress Julie Garner plays a fictional woman named Louise Gibson. The year is 1895, and Gibson wheels around her authentic 1898 bicycle (named Sylvia), upon which she has peddled to the museum from Takoma Park (then a recently-established railroad town).

“I’m out all on my own. Unchaperoned. And now I can meet complete strangers. This is exciting,” she told this reporter, before trying to convince him to join the League of American Wheelmen. (Founded in 1800, the league is now called the League of American Bicyclists.) Among the perks, she says, are a listing for members of sponsored hotels and discounts and maps that rank the quality of trails. “They could be fine, fair, good, bad, poor, vile: the officials terms for the quality of roads,” she says. “I recommend you stay away from the vile ones.”

By focusing on everyday objects, including the bicycle and orange juice cans, the exhibition is part of a broader movement at museums, says Suzanne Fischer, associate curator of contemporary history and trends at the Oakland Museum of California and author of the Public Historian blog.

“Lots of history museums do a similar thing—introducing visitors to the reasons we collect and different ways to read artifacts,” she says.

But, Fischer adds, there are two sides to such exhibits. On the one hand, visitors may feel personal connections to more recent objects, which conjure up memories and emotions. But that same familiarity can also lead some visitors to question how important the objects are. (If every home had Rembrandt paintings on its wall, one would assume that foot traffic at the Rijksmuseum would decrease dramatically.)

“Museumgoers often think that their own stories are too small or too trivial to be part of history,” Fischer says. “Hopefully exhibits like this one can help convince them otherwise. I think that visitors tend to expect masterpieces and great discoveries in museums, but history is also made of people’s lived experiences, the ordinary things, habits, events and textures of daily life. It is the museum’s responsibility to demonstrate this, to help visitors think about their own roles in history and the future.”

To that end, the museum’s eBay shopping presents a “definite advantage” to exhibiting recent, mass-produced objects, which are widely available and low-cost. But here too lies a trade-off because the ideal is to collect items whose owners’ stories illuminate those people’s “life experiences, the spirit of the era and the idiosyncrasies of the particular object,” according to Fischer.

“Museums are definitely doing more and more collecting on eBay,” she says. “For objects used like props that visitors can touch, it is the rule.”

The new permanent exhibition Object Project opens July 1 at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/00/9a/009ad76f-bfd9-4f26-bf0d-bc7ae900f3db/et20150714web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/29/98/2998bfc0-41d1-4cce-a05d-827e06867bb5/et20150720web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/02/38/0238c33c-f3b8-4992-9f97-76781395f51c/et20150740web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8b/64/8b647bbb-dc26-41cc-8eb8-c940dfa83142/et20150735web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/88/dd/88dd01de-890b-4302-98c2-23ea3446e2ea/et20150768web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)