Walter Cronkite and a Different Era of News

The legendary CBS anchorman was the “most trusted” man in America

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bc/a2/bca2bdb1-7848-4a28-bca7-beebb71facde/walter_cronkite_conducts_an_interview_in_hue_vietnam_february_1968.jpg)

No cable news. No satellite dish. No streaming internet video, no podcasts, not even a remote control. Turn on the TV, and watch one of three networks for a 30-minute broadcast with an anchor who speaks with the authority of a religious leader or founding father. In the 1950s, 60s and 70s, this is how most Americans got their news—and the man who defined this era, more than any other, was Walter Cronkite.

“For somebody of my generation, he was the pillar of American broadcast journalism,” says David Ward, a historian at the National Portrait Gallery. “He was always the responsible father figure. According to polls, he was the most trusted man in America—more than the first lady, the Pope or the president.”

Cronkite, born November 4, 1916, got his start in journalism working as a radio announcer for a series of stations in Missouri. But when he joined the United Press and left the country to cover World War II, he made his mark as a journalist capable of reporting stories in difficult conditions. “He’s flying over Berlin, and he’s at the invasion of Normandy and the ‘Bridge Too Far,’ the Battle of Arnhem. It was a total disaster, and he’s lucky to get out of there alive,” Ward says.

After the war, as the TV news era blossomed, Cronkite was there to become one of its key figures. While working for CBS in a variety of roles, hosting everything from morning shows to political conventions, he sat down in the “CBS Evening News” anchor chair and proceeded to hold it for nearly 20 years.

“Cronkite comes to national prominence in his second or third year, when he breaks the news that John F. Kennedy has been killed in Dallas,” says Ward. “There’s the famous moment where he starts to lose his composure, and he takes his glasses off, as he shares the news with the nation.”

One of the main elements of Cronkite’s appeal, though, was the fact that he presented the day’s news with an objectivity and reserve that Americans expected in anchormen at the time. “Authoritative, calm, rational—they explained the world to you,” Ward says. “The idea was that this was a very serious job, performed by various serious men.”

Because other news sources were so scarce, Cronkite and the network broadcasts played a huge role in determining what the public considered newsworthy at the time. “When Walter Cronkite signed off by saying ‘And that’s the way it is, Friday, November 5, 1972,’ that actually was what was important in the world,” says Ward.

Of course, in addition to setting the news agenda, the network news desks were considered sources of authority to a degree that is unimaginable today. “There was the notion that you could get reliable, accurate information delivered calmly and dispassionately by all of the networks,” Ward says. “That was the model.”

This view was linked to the deep-seated faith most members of the public held in the honesty of the government, as well as journalists—and although Cronkite was emblematic of the era, his innovative reporting and willingness to challenge authority were instrumental in bringing about its demise. “In 1968, he goes to Vietnam and does a documentary,” Ward says. “He hears one thing from the generals, and then he walks around and talks to GIs and Vietnamese, and he realizes there’s a disconnect.”

“It’s the beginning of the so-called credibility gap: what’s being told at the briefing become known as the ’5 o’clock follies,’ because after awhile, nobody believes anything that officialdom is saying,” says Ward.

Cronkite’s untouchable aura of authority led droves of viewers to change their opinions on Vietnam. “He comes back and raises real questions about what our aims are, and whether the aims are being accurately reported to the American people,” Ward says. “In 1968, there were plenty of people who were protesting the war in Vietnam. It’s the fact that he’s a firmly established, mainstream, church-going, centrist, respectable person that matters.”

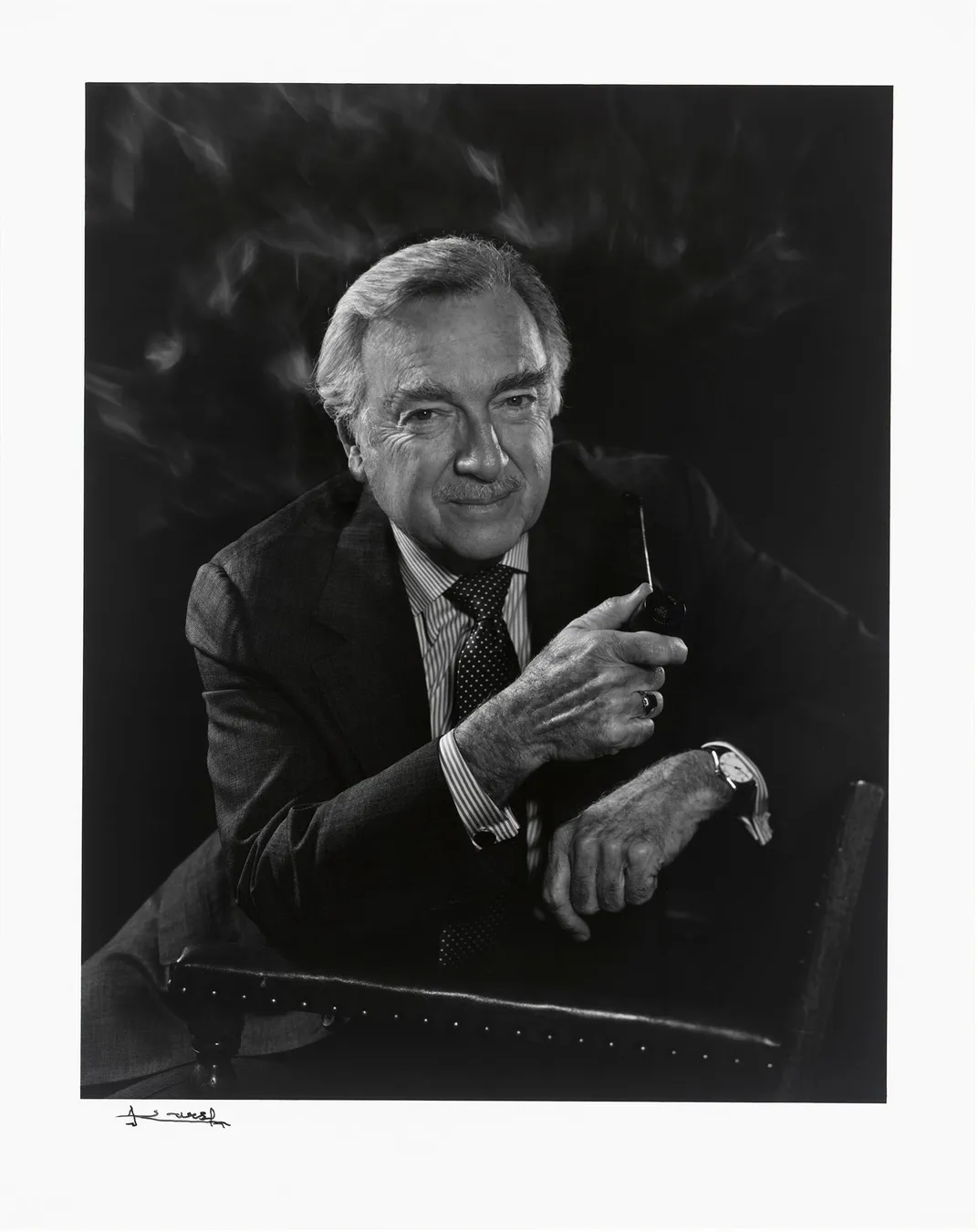

In 1971, Daniel Ellsberg, a former defense consultant, leaked the Pentagon Papers, a set of documents that provided evidence of systematic government wrongdoing and deception throughout the war. Public mistrust of the government reached a new level, and Cronkite’s interview of Ellsberg—captured in a photograph now among the National Portrait Gallery’s collections—became one of the many iconic moments of his career.

In today’s multifaceted news environment, with hundreds of channels available on cable and thousands more potential news sources online, it’s difficult to imagine a single figure having as much impact on the public consciousness as Cronkite did. “It’s so strange to think of that world,” says Ward. “That element of implicit authority, we just don’t have anymore.”

In 1981, CBS’s mandatory retirement age of 65 required that Cronkite step down from his post. Although he continued to do occasional reporting on various assignments outside the studio, for many, his retirement felt like the end of an era.

“This is my last broadcast as the anchorman of ‘The CBS Evening News,’” Cronkite said. ”For me, it’s a moment for which I long have planned, but which, nevertheless, comes with some sadness. For almost two decades, after all, we’ve been meeting like this in the evenings, and I’ll miss that.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)