Tracing the History of American Invention, From the Telegraph to the Apple I

More than 70 artifacts, from an artificial heart to an Etch A Sketch, grace the entryway to the American History Museum’s new innovation wing

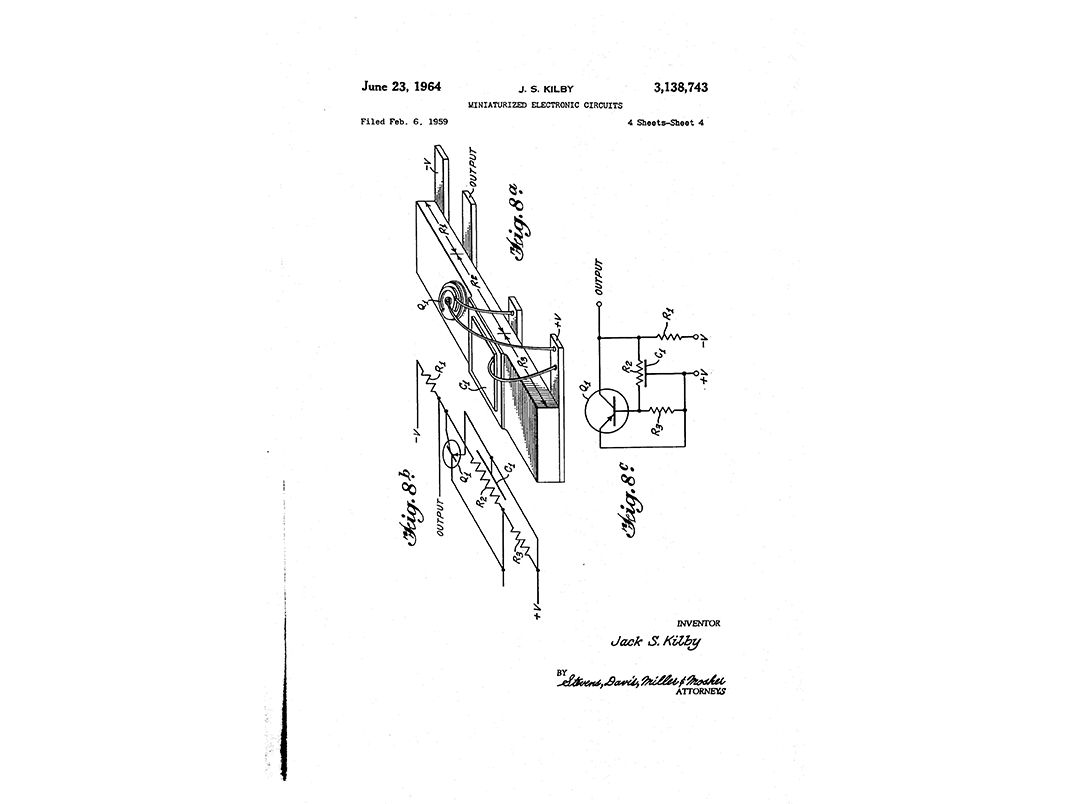

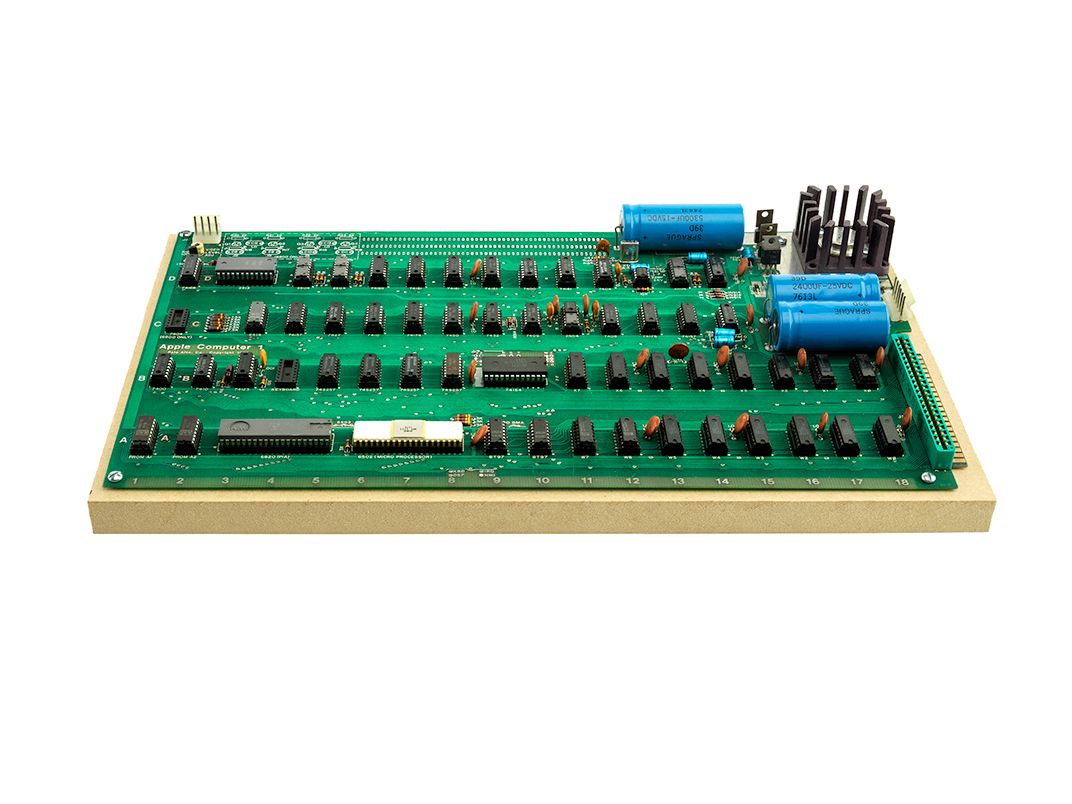

The Apple 1 product that Steve Wozniak built and subsequently sold in 1976 with Steve Jobs in an initial run of 100 personal computers consisted only of a circuit board, to which one had to add a monitor and case. The board was an affordable alternative in a sea of costly computers, and it transformed the way the world operated.

The Apple 1 board on display in one of the three glass cases in the exhibit “Inventing in America,” a collaboration of the National Museum of American History and the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), is one of four that collector Lonnie Mimms, 52, used to own before the museum acquired it. (Though never owned more than three at once, he clarified.)

Visiting “Inventing in America” a few days before it opened to the public, Mimms appreciated seeing the circuit board (Steve Jobs patent no. 7166791, Steve Wozniak patent no. 4136359) at the Smithsonian Institution.

“There’s a very surreal feeling seeing something that you possessed at one point that’s in a place of permanence,” he said. The exhibition, he noted, won’t be up forever, but having an object in the collections is “about as permanent as it gets. As long as the country exists, to think that this artifact will be sitting there.” (Mimms hopes that a couple of coins that he donated to the museum will also go on exhibit.)

A lifelong collector, who started with rocks, stamps and coins and still owns the first microcomputer that he acquired in the mid-1970s, Mimms is the CEO of an eponymous real estate firm in Roswell, Georgia. The city, some 20 miles north of Atlanta, is also where he is in the early stages of creating the Computer Museum of America. He hopes visitors to the American History Museum, particularly young ones, will appreciate seeing the Apple 1.

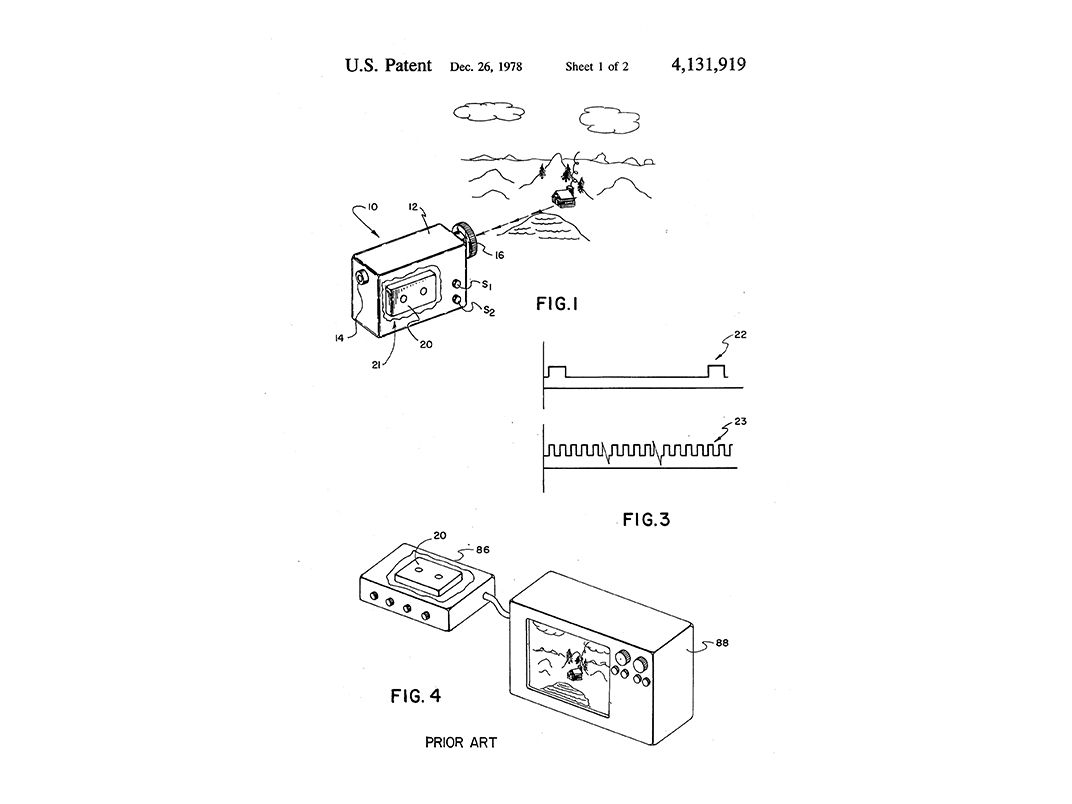

“All these things that are invented in the past have a connection to our current technologies,” he said, noting that the older objects connect younger people, who probably wouldn’t recognize landline phones, eight-tracks, vinyl records or even CDs, with antecedents of current technologies. “In most cases, almost anything you can pick up off the shelf that is a ‘current technology,’ you can either see a direct version of that in the past or certainly the roots of where it came from,” he said.

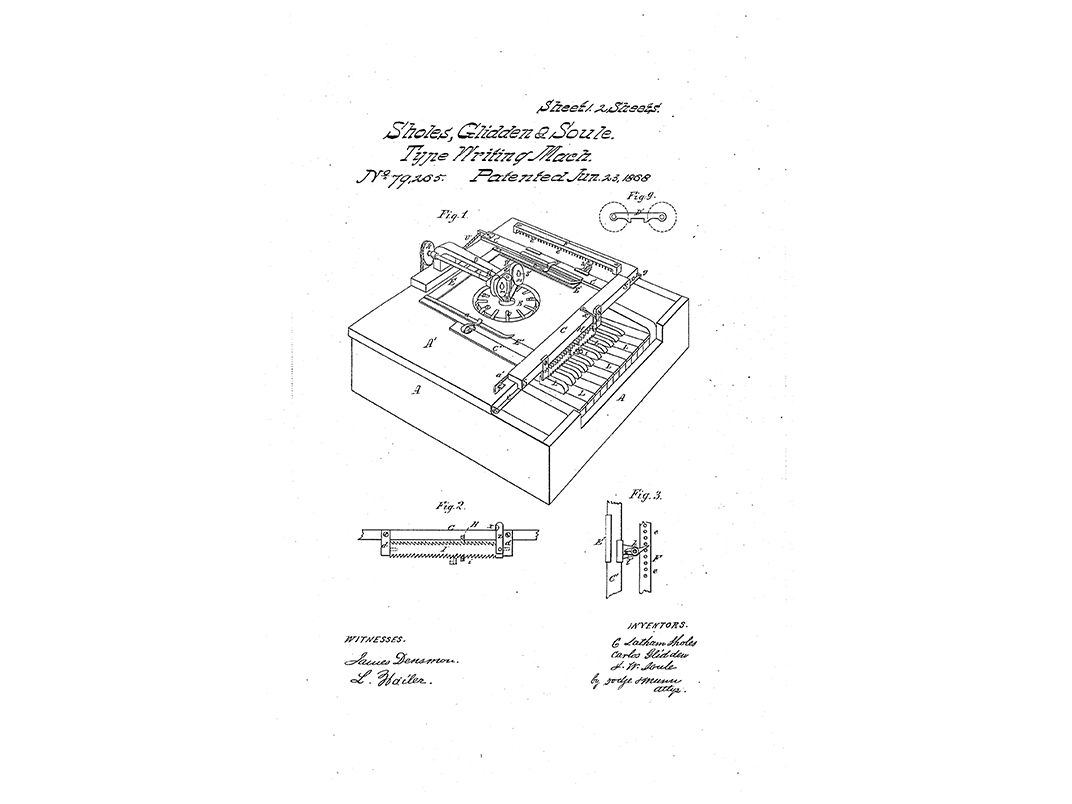

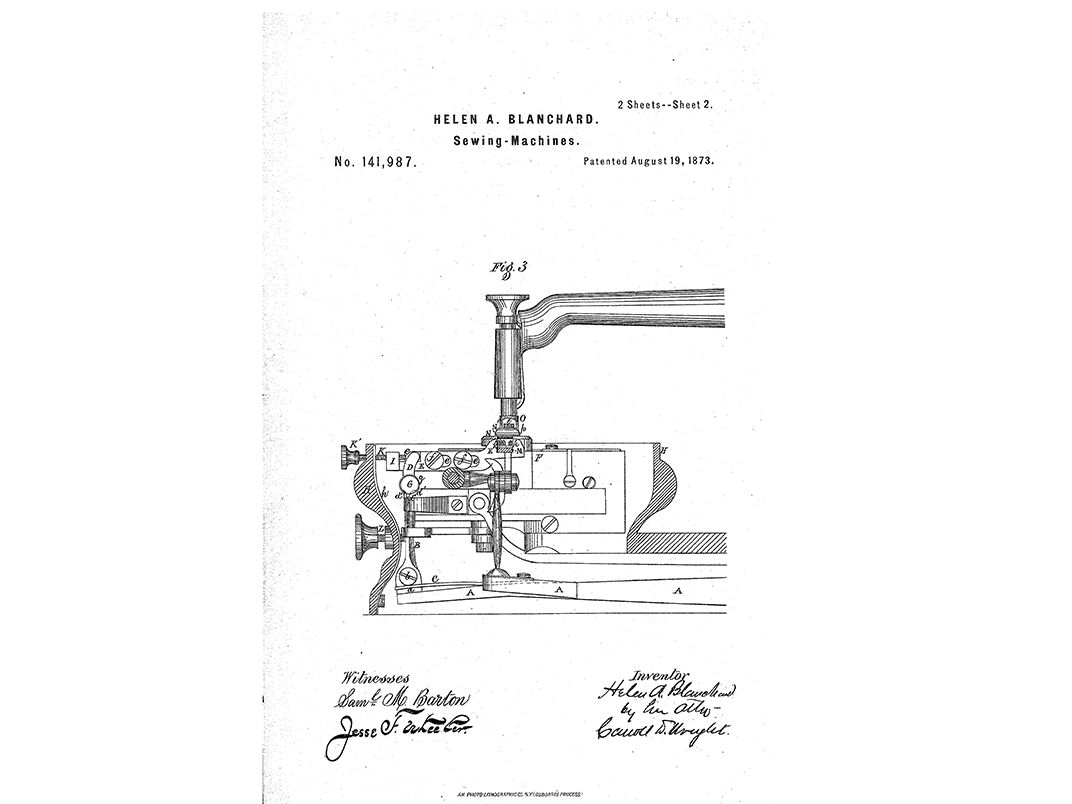

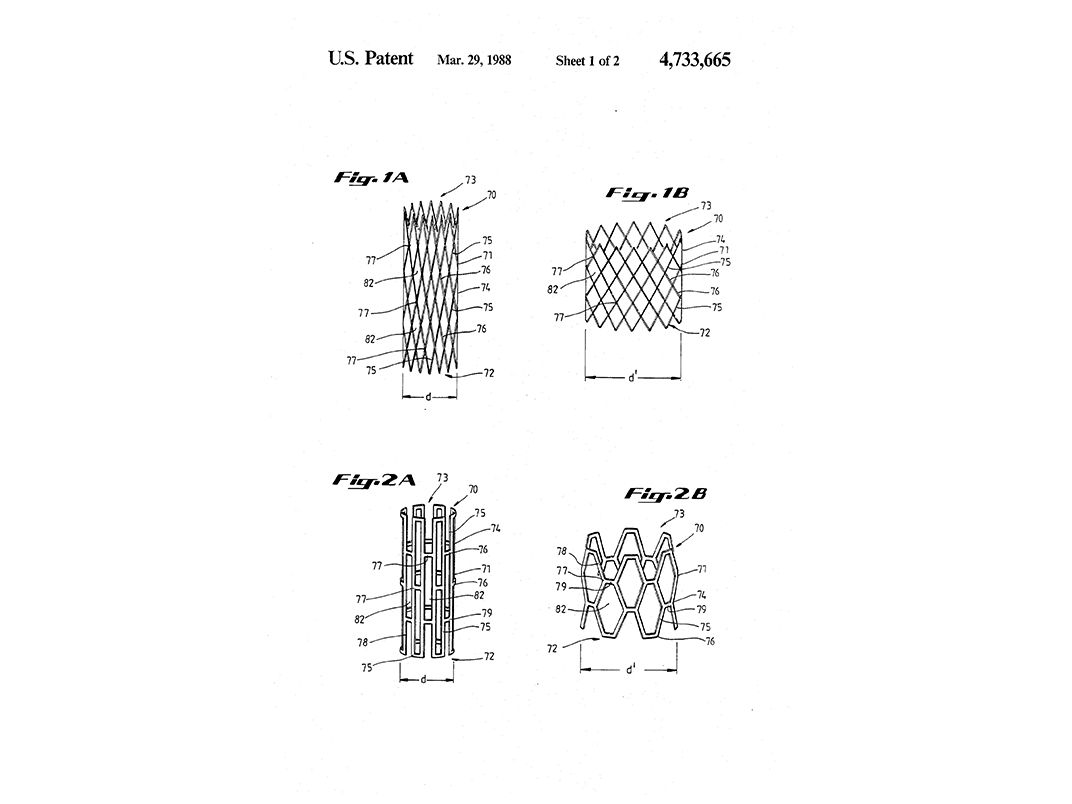

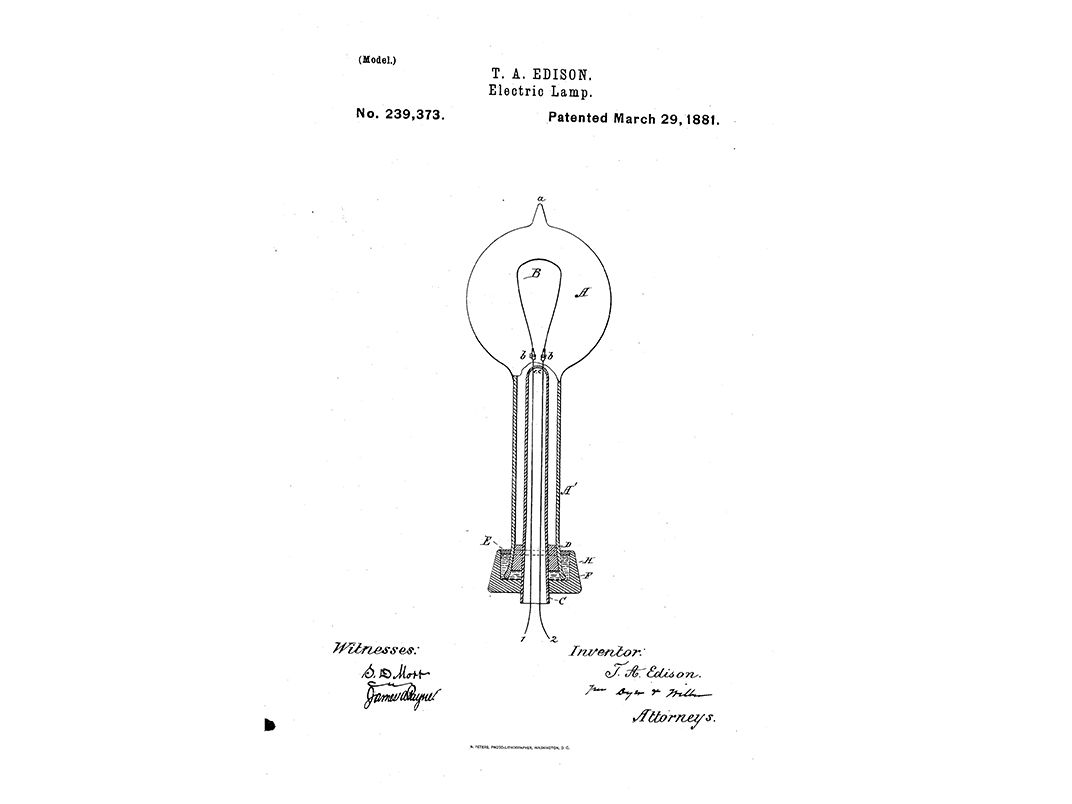

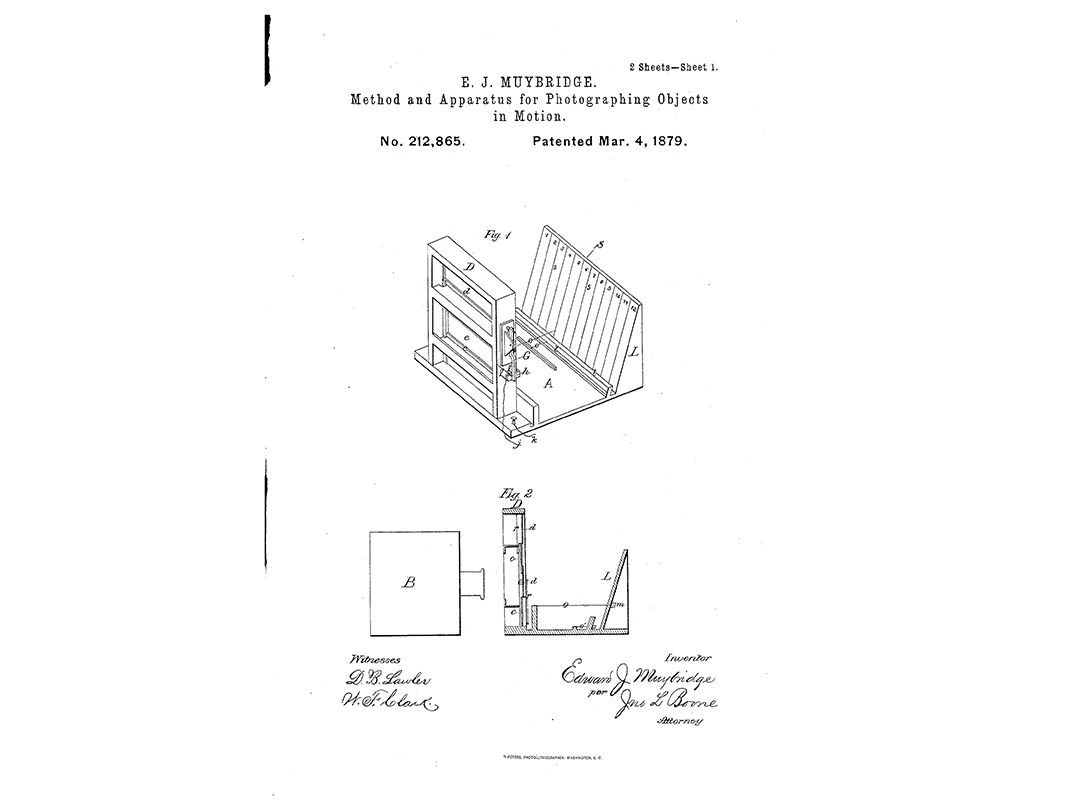

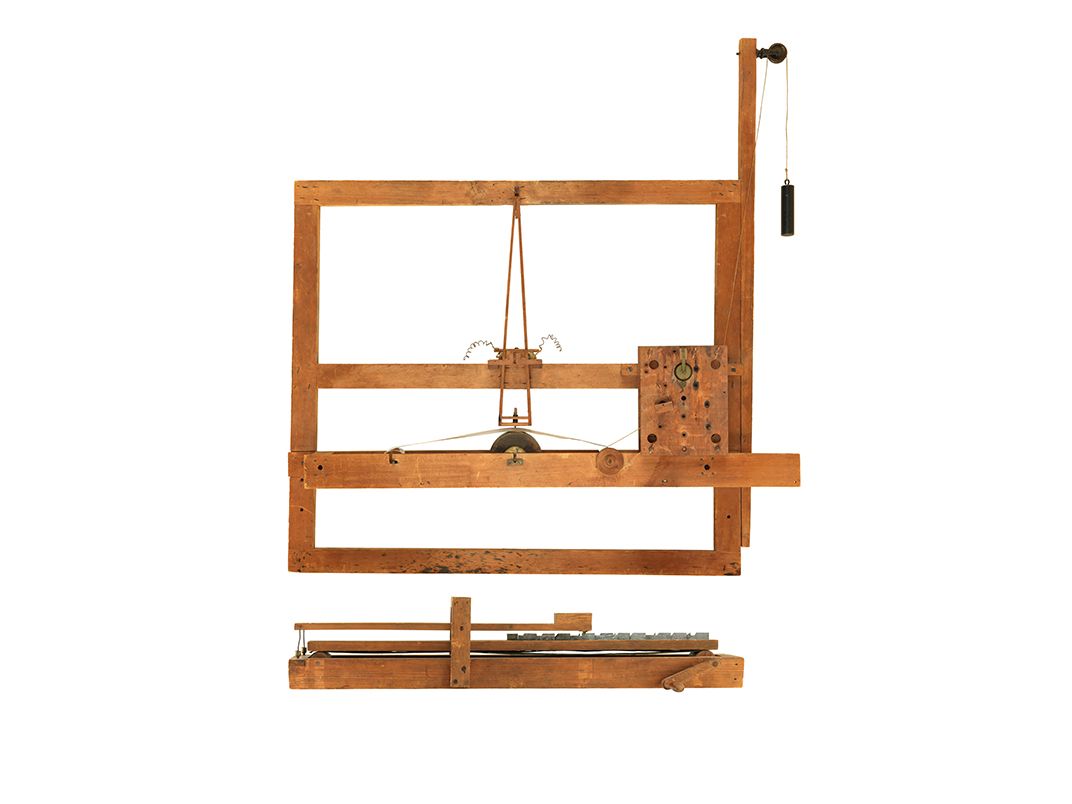

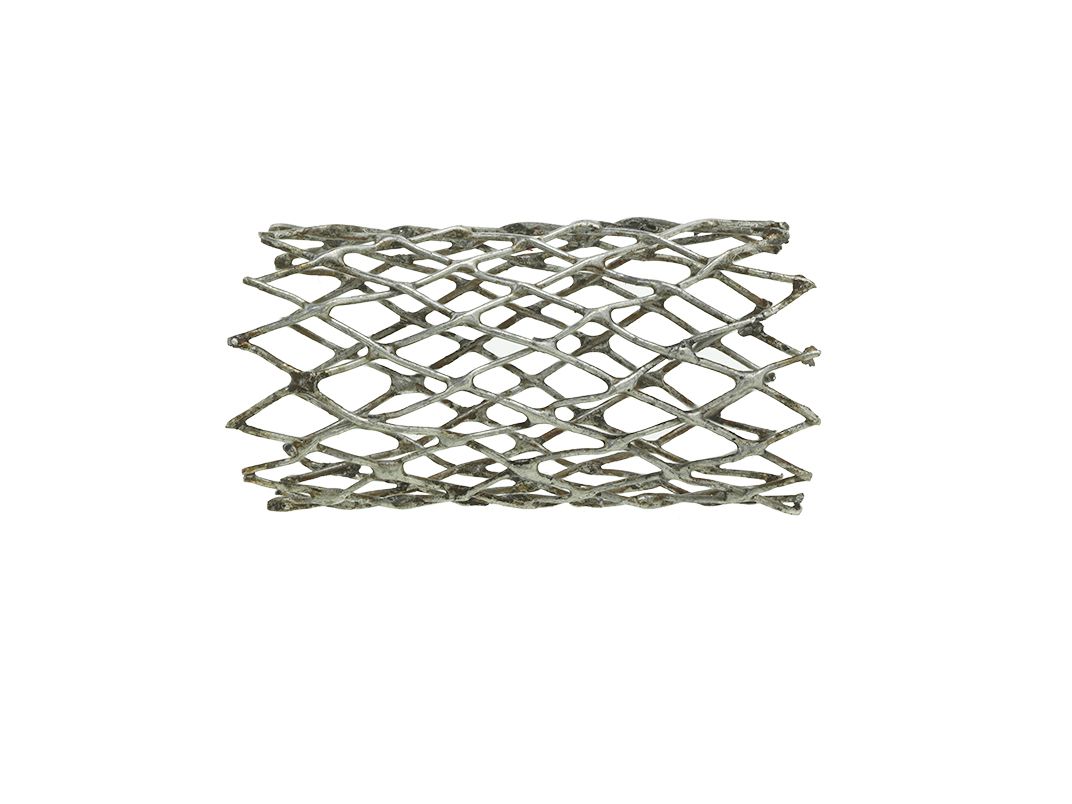

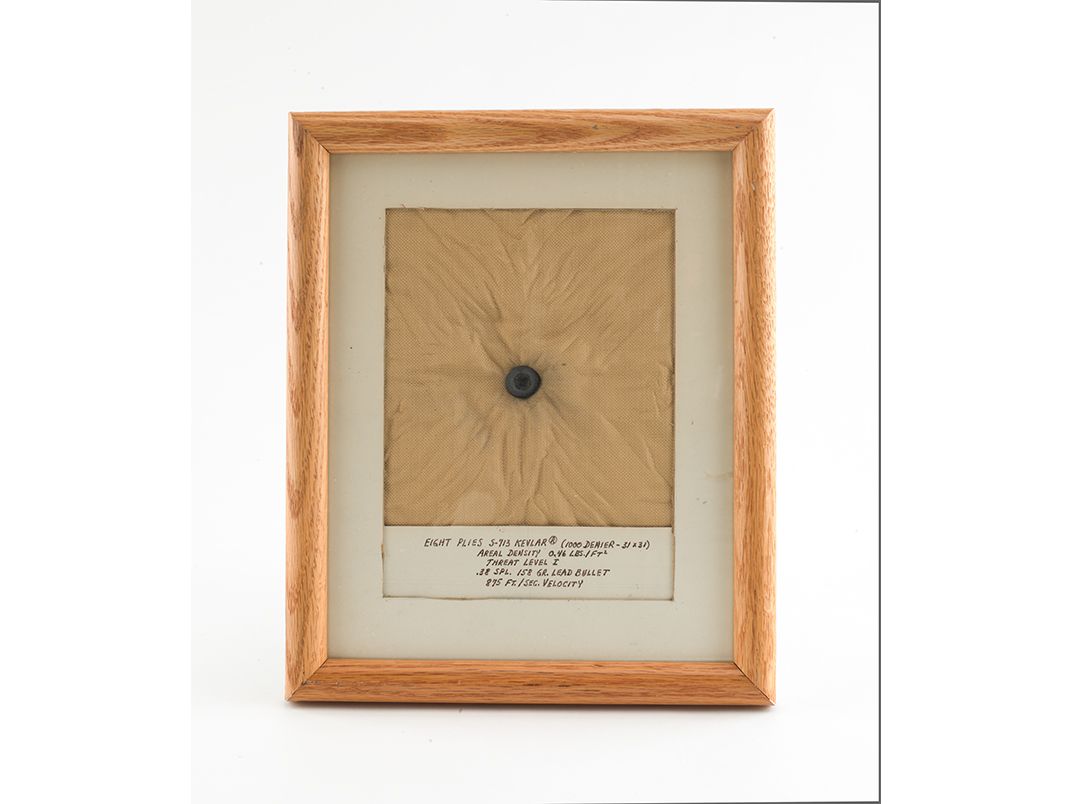

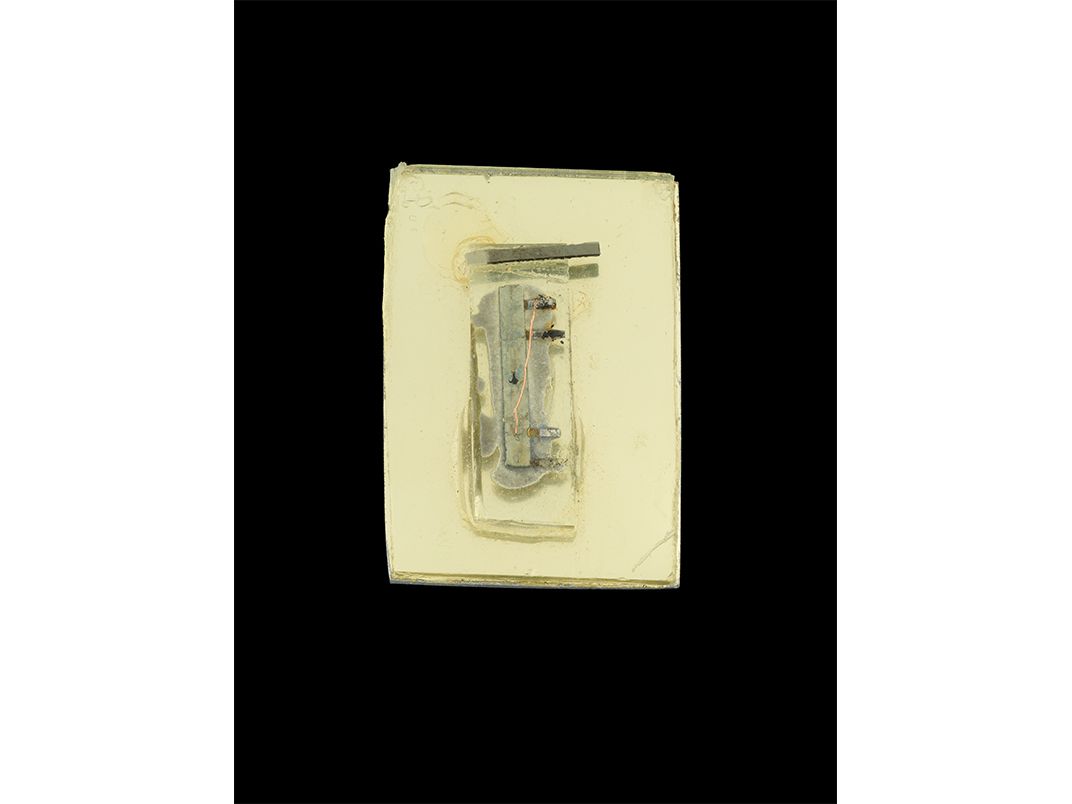

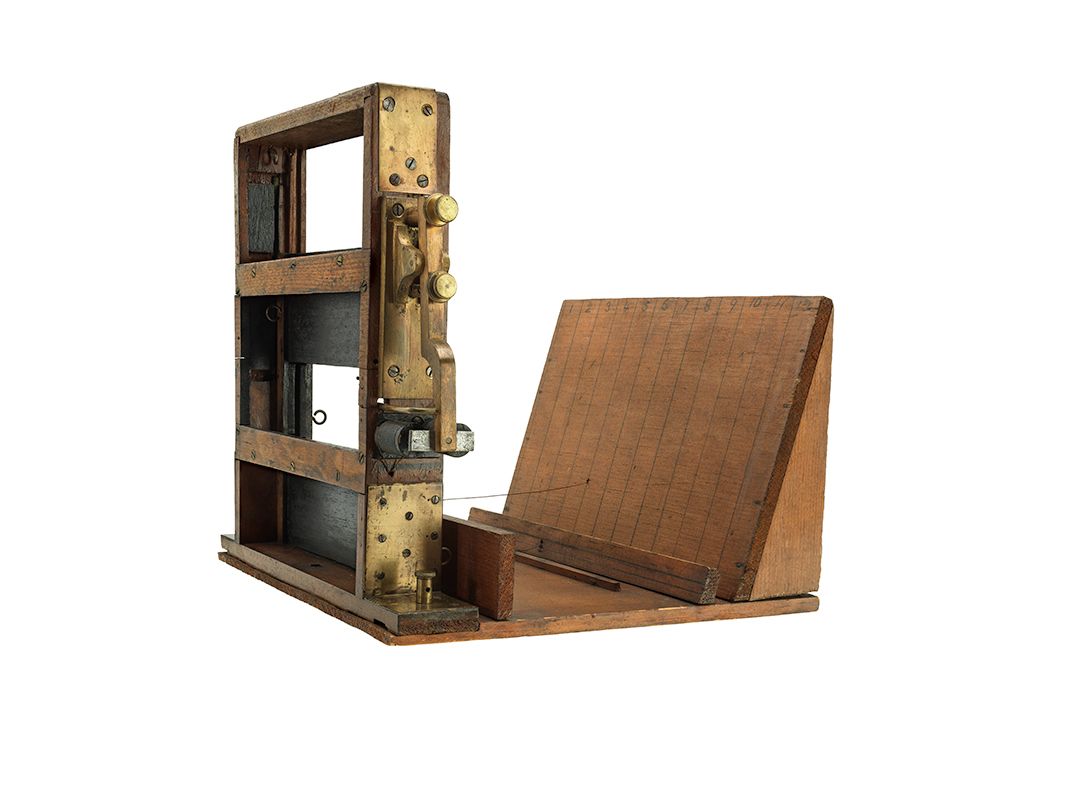

Not only does the same hold true for the 70 objects in the exhibit, which range from prototypes of Samuel F.B. Morse’s 1837 telegraph (made from an artist’s canvas stretcher) and Robert Jarvik’s artificial heart (1977) to an 1876 thermometer created by Gustav W. Schumacher (patent no. 172181) and the 1968 brick-and-mortar Pizza Hut design (no. 852458 for shape), but the objects tell a broader, distinctly American, story.

“America itself is an innovation,” said David Allison, the American History Museum’s associate director for curatorial affairs. “In our founding documents, in the Constitution itself, the Founders, who were not primarily aristocrats but were really businessmen, were thinking about how to protect people coming up with new ideas—to give them the protection that they need to turn that into something that’s going to make a profit or really have an impact.”

President George Washington signed a bill 225 years ago, on April 10, 1790, to lay the foundation of the current patent system. The legislation was the first in American history to recognize that inventors inherently possess rights to their creations. The first patent was issued in 1790. The one millionth patent followed in 1911, and the nine millionth was granted in 2015.

“More than two centuries of cumulative innovation have transformed our nation and our way of life in ways the Founding Fathers could never have imagined,” said under secretary of commerce for intellectual property and USPTO director Michelle K. Lee in a press release. “This exhibit will provide an exciting opportunity for the public to interact with and appreciate the role innovation has played in our country’s history.”

Embedded within the stories about American invention and innovation are also examples of the opposite, of companies that couldn’t evolve in necessary ways. “There are some very disruptive stories in the showcases,” Allison said. He noted a 1963 Carterphone (patent no. 3100818) on view, whose inventor, Thomas Carter, broke Bell System’s “natural monopoly” on phone services.

“You talk about Bell now and no one knows what that means,” Allison said. “It’s hard to believe now with all of the competing phone companies that there once was a natural monopoly.”

Other standouts in the show include White House China (1880, design patents D11932 and D11936), Coca-Cola bottles (1977, reg. no. 1057884 for shape), an Oscar statuette (reg. no. 1028635 for shape), Mickey Mouse ears hat (1975, reg. no. 1524601 for shape), a Mrs. Butterworth syrup bottle (1980, reg. no. 1138877 for shape), an Etch A Sketch drawing toy (1998, reg. no. 2176320 for color and shape) and the yellow borders of National Geographic magazines (1977, reg. no. 1068503 for color and design).

A group of museum staff selected the prototypes, patent models and products to display. “Everybody brought their favorites to the table,” said Allison. “We debated.” It was an opportunity to bring some of the museum’s most visually compelling inventions out of storage and on view, to catch visitors’ eyes as they enter the innovation wing.

One of Allison’s personal favorites is Morse’s telegraph. “It’s one of those things that once you see it, you can see where it came from, you can see how it works, you can see the principles,” he said, “And then you can see it’s a new idea, but it needs to be refined.”

The American History Museum’s collection of patent models, alone, is impressive. In 1908, the museum acquired 284 models—all submitted by inventors in accordance with 19th-century patent application guidelines—from the U.S. Patent Office. Now there are more than 10,000 in the trove.

“If we had a case twice this size, we’d easily fill it,” Allison said.

The cases, and their ingenious shelving system that raises or lowers to allow for objects of different sizes, which was created in-house by Farah Ahmed, a museum designer, and built in the cabinet shop by Peter Albritton, are also quite innovative.

“In fact, Farah was thinking about patenting this shelving system,” Allison said.

The new exhibition “Inventing in America,” which opened July 1, is on view in the Innovation Wing at the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)