This is the Carriage That Took Lincoln on his Fateful Trip to Ford’s Theatre

As the April anniversary of Lincoln’s last ride approaches, an historian recounts the president’s other horse and buggie moments

:focal(668x173:669x174)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/11/52/11526198-78a9-4689-ad63-e6a263e24785/rws201504706web.jpg)

Gaudy Civil War generals, and even muddy-booted infantrymen, sometimes found it hard not to chuckle at the sight of Abe Lincoln on a horse.

It’s not that the president was awkward in the saddle; after years as a circuit-riding lawyer on the prairie, he handled his mount with ease and confidence. But occasionally there was a mismatch between horse and rider, as when he went down to review Fighting Joe Hooker’s cavalry along the Rappahannock before the battle of Chancellorsville. Lincoln was six feet four, plus another foot for his tall beaver hat, and his borrowed horse was too small.

One of the soldiers who stood at attention watching this “incongruous apparition” said the president’s toes seemed about to drag the ground as he rode past regiment after regiment, looking dead serious while his pant legs crept up till they exposed his long white underwear. The whole thing “touched the sense of fun in the volunteers,” but they dared not laugh. A simple notice ahead of such visits might have prevented later such scenes, but no, he drew a comically undersized steed again that fall at Gettysburg, where he went to dedicate the vast new cemetery.

Lincoln managed more dignity in Washington, where he rode a big, comfortable gray horse to and from his summer retreat at the Soldiers’ Home. The poet and wartime nurse Walt Whitman noticed this one day as the president passed amid a cavalry escort at Vermont Avenue and L Street. Lincoln valued those hours commuting on horseback because they gave him time to think without interruption, but he often needed to do business while on the move.

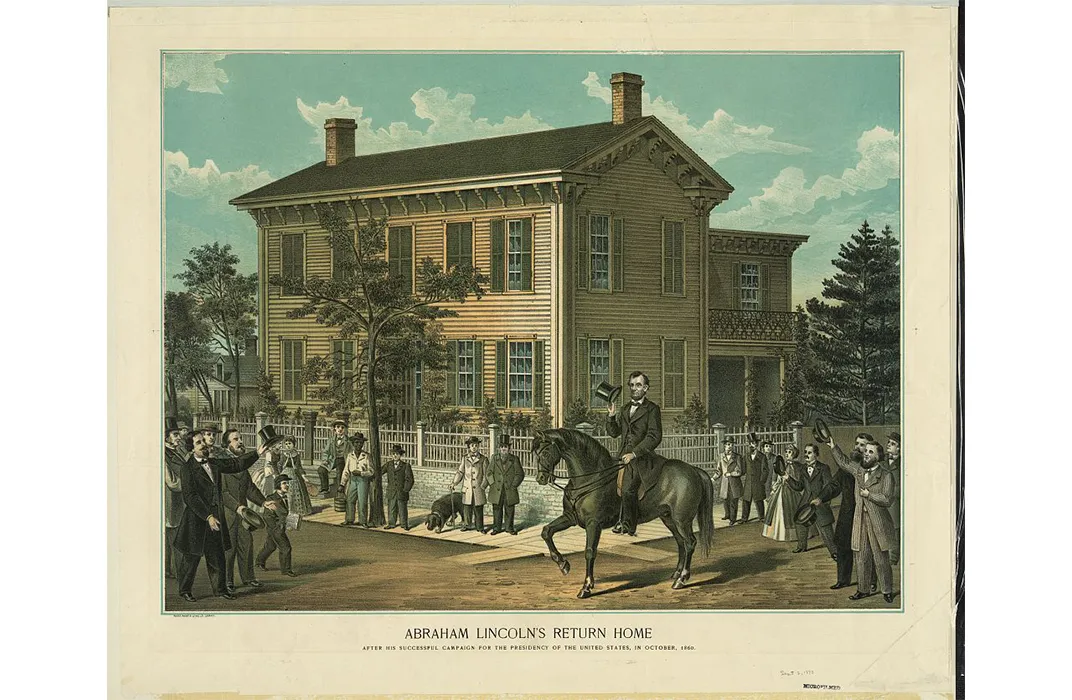

Starting the day he arrived in Washington, he and Senator William H. Seward, who would become his secretary of State, spent many hours touring the town in a carriage, talking political strategy. That first Sunday, they sat up front at St. John’s Church, “the church of presidents,” on Lafayette Square 300 yards from the White House, where hardly anyone recognized the president-elect.

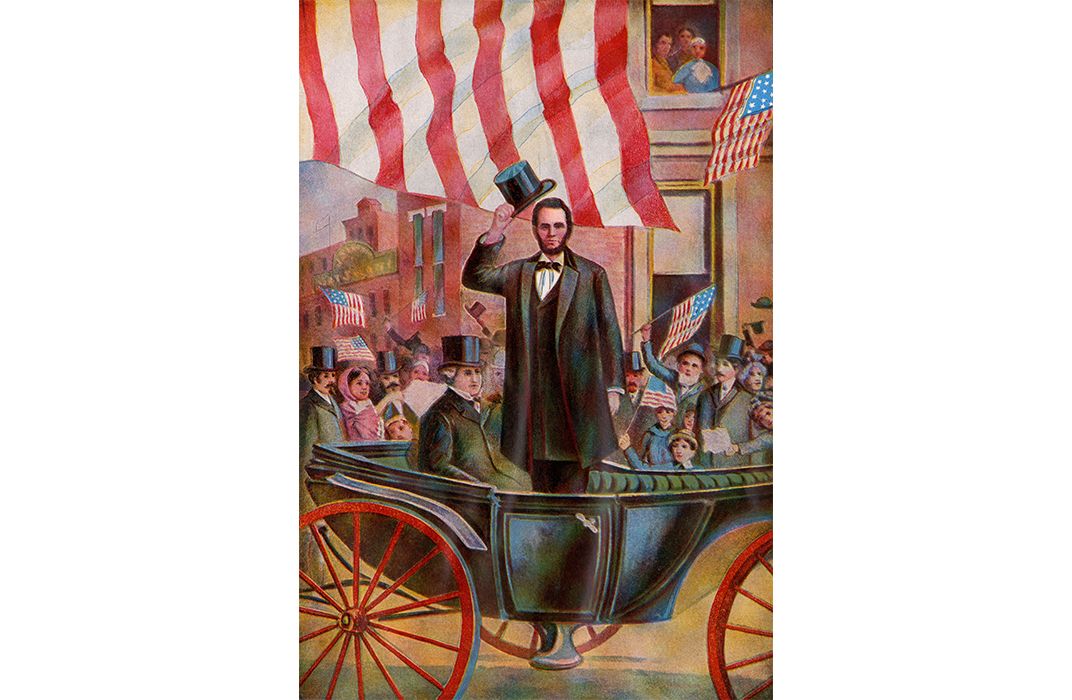

Amid happy crowds and nervous security details, Lincoln sat beside outgoing President James Buchanan as they headed up Pennsylvania Avenue to the Capitol for his first inauguration. His voice grew husky when he closed his address with a near-religious affirmation that “The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearth-stone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.” Then as he and Buchanan rode back toward the White House, he stopped their carriage to demonstrate his belief in the whole Union by playfully kissing each of the 34 young women who stood representing all the states, north and south.

Somehow, in the up-and-down months that followed, carriages seemed to convey sadness more often than hope. There was the stormy day in early 1862 when the grieving president took his carriage to the burial of his beloved son Willie, dead of typhoid fever at the age of eleven. For days, Lincoln wept silently, and the distraught Mary wailed until she seemed insane. The following year, a screw holding the coachman’s seat on Mrs. Lincoln’s carriage broke as she came down from the Soldiers’ Home. The driver fell into the street and the horses panicked. Mrs. Lincoln toppled overboard, striking her head on a rock and suffering a nasty gash that got infected. Not long afterward, her carriage injured a little boy who stepped into its path from a horse-drawn streetcar.

In mid-1863, Lincoln sat with Seward and secretary of War Edwin Stanton on the way to the funeral of one of Stanton’s children. Heading into the countryside, the president confided to them that he was considering whether he might end slavery by simply proclaiming the slaves free. Then he did issue the Emancipation Proclamation, and it was a moral triumph. But casualties ran so high the following summer that a miasma of death hung over the capital. The gloom deepened when 23 young women were burned to death in an explosion at the arsenal; Lincoln and Stanton rode as chief mourners in a procession of 150 carriages from the mass funeral at Congressional Cemetery.

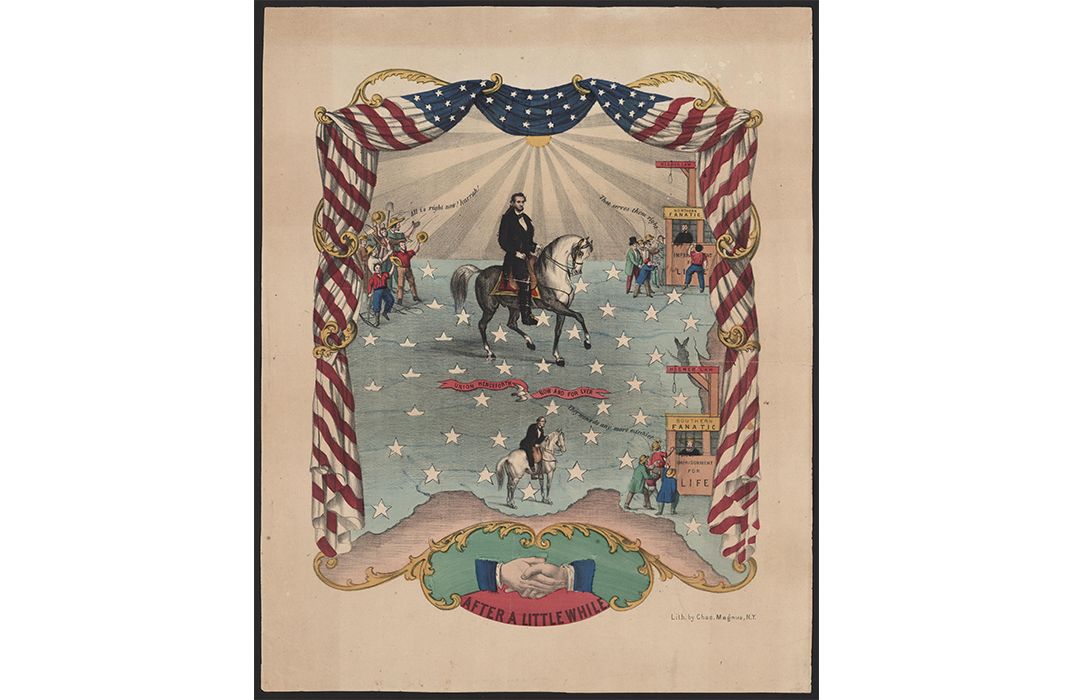

That fall, after victories on the battlefield and at the ballot box, the end of all the blood and tears seemed visible. After Lincoln’s re-election, a group of New York merchants presented him a new carriage, a polished dark green barouche that was just right for the serious but optimistic mood of his second inauguration. With spring came news that Richmond had fallen, and he immediately went down by boat to see the battered capital of the Confederacy. He rode about the city in a carriage with General Godfrey Weitzel, through burned-out streets and past the infamous Libby Prison where so many captured Union officers had been held.

When the general asked how the defeated enemy should be treated, the president expressed his postwar policy in a single sentence: “Let ‘em up easy.” Five days later, Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House, and the president and his lady started looking ahead again, not only to a nation at peace but to more time with each other.

On Friday, April 14, 1865, Mary Lincoln organized a theater party, to see a lighthearted comedy called Our American Cousin. General and Mrs. Grant accepted an invitation to join them, but then the general changed his mind and they left to visit their children in New Jersey. Mary suggested canceling the outing, but the president said no, he didn’t want to disappoint people who expected to see them at the theater. She asked nearly a dozen others before Major Henry Rathbone and Clara Harris, a glamorous young couple from across Lafayette Park, agreed to come along.

The president ate an apple for lunch at his desk, then he and Mary took a carriage ride in the afternoon, stopping to inspect the battle-scarred gunship Montauk at the Navy Yard. He seemed chipper as they wound about the capital, and even talked wistfully of going back to Illinois some day to start a law office. He told her that for three years since Willie’s death, they both been miserably sad, and now with the war ending, they should try to be more cheerful.

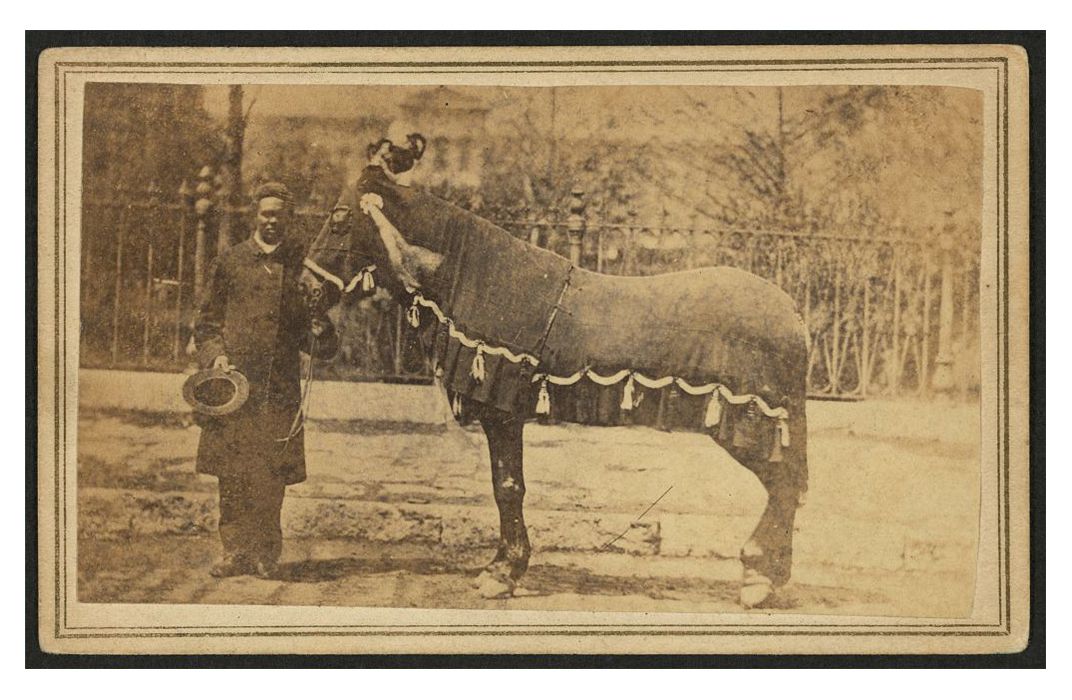

That was his mood as he sent his youngest son Tad off to a special show at Grover’s Theater early that evening. He brushed aside a premonition of danger voiced by one of his guards, and cheerfully greeted Henry and Clara when he and Mary joined them in the president’s carriage. Shortly after eight o’clock, they departed the White House for the nine-block trip to Ford’s Theater on Tenth Street. It was their last carriage ride together.

Visitors to the National Museum of American History can view the open barouche model carriage that transported President Abraham Lincoln, Mary Lincoln, Major Henry Rathbone and his fiancée Clara Harris to Ford's Theatre through May 25, 2015. The 1864 Wood Brothers carriage was presented to Lincoln by a group of New York merchants shortly before the president's second inauguration. Equipped with six springs, solid silver lamps, door handles and hubcaps, the carriage has steps that rise and lower as the door is opened.

Freedom Rising: Washington in the Civil War

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSCN0003-001.JPG)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSCN0003-001.JPG)