Snake Found in Grand Central Station!

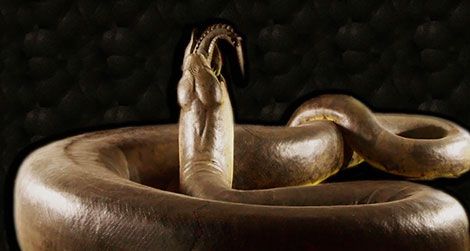

Sculptor Kevin Hockley unveils his fearsome replica of Titanoboa

In January 2011, the Smithsonian Channel approached Kevin Hockley, an Ontario-based model maker, with a tall (and rather long) order: Build us a snake.

Several years ago, Carlos Jaramillo, a paleontologist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, and scientists from the University of Florida, University of Toronto and Indiana University unearthed fossils of a prehistoric snake in northern Colombia. To tell the story of the discovery, the film producers wanted a full-scale replica of the creature.

The snake, however, was not your typical garter snake or rattlesnake, which Hockley had sculpted before, but Titanoboa, a 2,500-pound “titanic boa” as long as a school bus that lived 58 million years ago.

Hockley’s 48-foot long replica of Titanoboa slurping down a dyrosaur (an ancient relative of crocodiles), is being unveiled today at Grand Central Station in New York City. The sculpture will be on display through March 23, and then it will be transported to Washington, D.C., where it will be featured in the exhibition “Titanoboa: Monster Snake” at the National Museum of Natural History, opening March 30. Smithsonian Channel’s two-hour special of the same title will premiere on April 1.

“Kevin seemed like a natural choice,” says Charles Poe, an executive producer at the Smithsonian Channel. Poe was especially impressed by a narwhal and a 28-foot-long giant squid that the artist made for the Royal Ontario Museum. “He had experience making museum-quality replicas, and even more important, he’d created some that seem larger than life. When you’re recreating the largest snake in world history it helps to have a background in the fantastical,” Poe says.

In fact, Hockley has been in the business of making taxidermy mounts and life-size sculptures for more than 30 years. He mounted his first ruffed grouse as a teen by following instructions from a library book. Hockley spent his high school years apprenticing as a taxidermist in Collingwood, Ontario, and he worked a dozen years at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, creating mounts as well as artistic reconstructions of animals and their habitats. Today, as owner of Hockley Studios, a three-person operation headquartered on the 15-acre property where he lives, near Bancroft, Ontario, he builds bronze sculptures of caribou, lynx and wolves and life-like replicas of mastodon and other Ice Age animals, such as extinct peccaries and jaguars, for museums, visitor centers and parks.

Creating Titanoboa wasn’t easy. Scientists piecing together what the prehistoric creature might have looked like provided Hockley with some basic parameters. “They linked it strongly to modern-day snakes, which was very helpful,” says Hockley. “It was sort of a blend of a boa constrictor and an anaconda.” He studied photographs and video of boas and anacondas and visited live specimens at the Indian River Reptile Zoo, near Peterborough, Ontario. “I could see the way the skeleton and the musculature moved as the animal moved,” says Hockley. “There are all these little bulges of muscle at the back of the head that convey the animal’s jaws are working.” He made sure that those bulges were on his model. Hockley also noted the background colors of anacondas and the markings of boa constrictors. Jason Head, a vertebrate paleontologist and herpetologist at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, surmised that the coloration of the prehistoric snake might have been similar. “Of course, this is speculation,” says Hockley. “It could have been pink with polka dots for all we know.”

The first step to building the replica was coming up with a pose. Hockley produced a scale model in clay, an inch of which represented a foot of the actual replica. The snake’s body forms two loops, where museum visitors can wander. “I tried to make it interactive, so you can actually get in and feel what it is like to be surrounded by a snake,” says Hockley. He stacked large sheets of 12-inch-thick Styrofoam high enough to make a snake with a 30-inch circumference. He drew the pose on to the Styrofoam and used a chainsaw, fish filet knives and a power grinder with coarse sand paper disks on it to carve the snake. Hockley applied paper mâché to the Styrofoam and then a layer of polyester resin to strengthen it. On top of that, he put epoxy putty and used rubber molds to texture it with scales. “The hardest part was trying to make the scales flow and continue as lines,” he says. When the putty dried, he primed and painted the snake. He started with the strongest markings and then layered shades over the top to achieve the depth of color he desired. “It makes the finished product that much more convincing,” he says. The snake was made in six sections to allow for easier transport, but devising a way to seamlessly connect the parts was also tricky. Hockley used a gear mechanism in a trailer jack, so that by racheting a tool, he can draw the pieces tightly together.From start to finish, construction of the replica took about five months. As for materials, it required 12 four-foot-by-eight-foot sheets of Styrofoam, 20 gallons of polyester resin, 400 pounds of epoxy resin and numerous gallons of paint. Smithsonian Channel producers installed a camera in Hockley’s studio to create a timelapse video (above) of the process.

“It was an amazing opportunity,” says Hockley. The artist hopes that his model of Titanoboa gives people an appreciation for how big animals could be 60 million years ago. Since snakes are coldblooded, the size they can attain is dependent on the temperature in which they live, and temperatures during Titanoboa‘s time were warmer than today. As a result, the snake was much bigger than today’s super snakes. “Hopefully they will be awestruck by its realism,” he says. “A little bit of fear would be nice.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)