Shark Attack! (In a Fossil)

A new discovery sheds light on a three-million-year-old shark bite

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20111116112007whale-fossil-small.jpg)

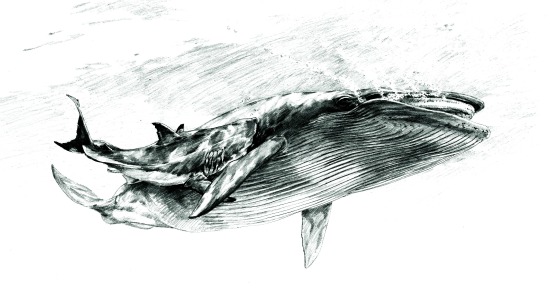

Workers at a North Carolina mine recently came across an unusual fossil. It looked like a piece of a giant bone, but had three strange piercings spaced evenly across the surface. When paleontologist Stephen Godfrey of the Calvert Marine Museum got a hold of the specimen, he came up with a hypothesis that was pretty surprising. Godfrey thinks it may be the rib of 3 to 4 million year old whale, with wounds sustained after a bite from a large-toothed shark.

“There are three points where you have a mound with a dip surrounding it, and they are evenly spaced,” says Don Ortner, an anthropologist at the Natural History Museum who collaborated with Godfrey on the analysis. “There aren’t many things that do that. In fact, there aren’t any other than a bite.”

The fact that the thick bone specimen appears to come from a whale—likely an ancestor of a great blue or humpback—helped researchers narrow down the identity of the predator. Of the potential aquatic creatures that might have done it, the six-inch spacing between marks led Godfrey to the conclusion that it was likely Carcharocles megalodon, an extinct shark species known for its enormous jaw.

When Ortner, an expert on calcified tissue, looked at the specimen, he came to yet another unexpected finding: the whale appears to have survived the attack. Each of the piercings was surrounded by a small mound of regenerated tissue, and the entire specimen was covered with a material known as woven bone. “This occurs in lots of situations,” Ortner says. “When you break a bone, for example, the initial callus that forms is always woven bone. It forms very rapidly, as the body tries to restore biomechanical strength as quickly as possible.”

“In this particular case, we not only have the reactive bone forming where the impact from the teeth occurred, we have woven bone spread over the entire surface of the bone fragment,” Ortner says. “So that we know that something beyond the initial trauma has occurred, and that is most likely infection.”

However, the woven bone also told Ortner that the whale hadn’t survived too much longer after the bite, since its recovery was incomplete. ‘Woven bone is not good quality bone, and with time, the body will fill it in,” he says. Ortner and Godfrey estimate the whale died two to eight weeks after the attack.

The research team, which also includes Robert Kallal of the Calvert Marine Museum, recently published their findings in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. Their discovery, they believe, is one of very few examples in paleontology of a fossil showing evidence of a predation event that was survived by the victim.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)