‘Mr. President, How Long Must Women Wait For Liberty?’

In January 1917, women took turns picketing the White House with a voice empowered by American democracy

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/64/89/6489b999-95c2-4486-9cc4-d388463231ea/flag_1-wr.jpg)

This rectangle of yellow cloth is small, only seven by nine inches, but it tells a much larger story. It begins in January 1917, when the National Woman's Party (NWP), led by Alice Paul, set up a silent picket outside the White House gates.

After years of meetings with President Woodrow Wilson that had failed to produce results, suffragists decided to use the White House building as a stage to influence the man inside.

Their goal was to make it "impossible for the President to enter or leave the White House without encountering a sentinel bearing some device pleading the suffrage cause," according to an article in the Washington Post on January 10, 1917. Women took turns standing with signs bearing slogans such as, "Mr. President, How Long Must Women Wait For Liberty?" and "Mr. President What Will You Do For Woman's Suffrage?" Their actions were covered extensively in newspapers across the country, sparking intense debate and garnering both support and derision from crowds that gathered to view the spectacle the women made.

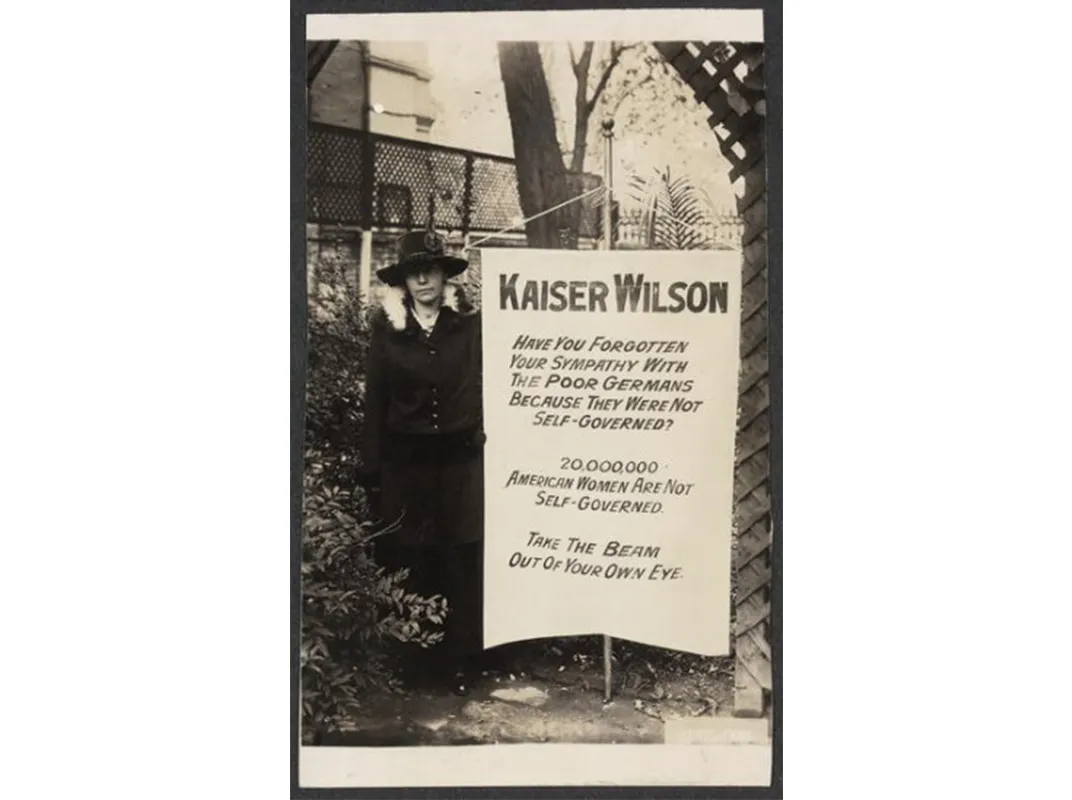

As the protest continued, suffragists created a series of banners taunting "Kaiser Wilson." The banners compared the president to the German emperor and were intended to point out what the suffragists saw as hypocrisy on the part of President Wilson to support the cause of freedom in the First World War yet not support the freedom of women at home. The statements came across to some onlookers as disloyal and unpatriotic, particularly during a time of war.

On August 13, 1917, a crowd began to taunt and intimidate the suffragists. Some even began pelting the women with eggs and tomatoes.

Soon the growing crowd graduated to tearing the banners from the suffragists' hands and ripping them up for souvenirs. Defiant, the picketers produced still more banners, only to have them taken from them as well. By the end of the day, the women had lost at least 20 banners and 15 color standards to an angry crowd that grew to more than 3,000. Two men were arrested in the fracas, and the scrap of fabric from a banner reading "Kaiser Wilson Have You Forgotten…" was seized by District of Columbia police. It remained in their possession for 25 years, until the department gifted it to the National Woman's Party Headquarters.

Eventually, the fabric scrap made its way into the belongings of Alice Paul, the founder of the NWP and leader of the pickets. It was donated to the Smithsonian in 1987 by the Alice Paul Centennial Foundation as a tangible reminder of the hard-fought battle for woman's suffrage. But it is also part of an important story about the relationship between the people and the president

The women on the picket line were participating in an American tradition that had been in existence since the nation's founding: that of bringing the grievances of the citizenry directly to the chief executive at his home, the Executive Mansion (as the White House was then known). "The People's House," as the nickname suggests, was conceived as a building belonging to all citizens, akin to the democratic government itself, and contrasted with the untouchable palaces associated with a monarchy.

The White House building is both a means for and a symbol of the people's access to and participation in their governance. Throughout the 19th century, the American people had been accustomed to almost unlimited access to the house and to the president. Tourists wandered in and out of the building and petitioners waited for hours to bring their particular concern to the president. In 1882, as a plan to replace the deteriorating mansion was being floated in Congress, Senator Justin Morrill made objection on the grounds that the building itself was inextricably tied to the people's relationship to the president:

"'Our citizens have long been wont to visit the place, and there to take by the hand such Chief Magistrates as Jefferson, Adams, Jackson, Lincoln and Grant. They will not surrender their prescriptive privilege to visit the President here for the drowsy chance of finding him not at home after a ride of miles away out of town. He must be accessible to members of Congress, to the people, and to those who go on foot; and we have never had a President who even desired a royal residence, or one so far removed as to be unapproachable save with a coach and four. Our institutions are all thoroughly republican in theory, and it will be agreed they should remain so in practice.'" (S. Doc. No. 451, 49th Cong., 1st Sess. 1886)

Like so many Americans before them, the picketers came to the White House to use the voice American democracy had empowered them with. Unlike so many others, they found the best way for them to use that voice was outside the White House, not within. When the NWP took their conversation with President Wilson to the gates, they effectively established a new form of public interaction with the White House, a new way in which the people could access and "own" the "People's House," a tradition that would only become more popular over the next several decades, and which continues to this day.

Bethanee Bemis is a museum specialist in the division of political history at the National Museum of American History. This article was originally published on the museum's blog "Oh Say Can You See."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Bemis_Bethanee_2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Bemis_Bethanee_2.jpg)