Scientists Discover a Large and Feathered Dinosaur that Once Roamed North America

The ‘Anzu wyliei’ species looks like a cross between a chicken and a lizard

:focal(1380x300:1381x301)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/83/49/8349655b-19ee-45fc-8e60-bbcfdea72155/lamanna_et_al_-_media_art_1_mark_klingler.jpg)

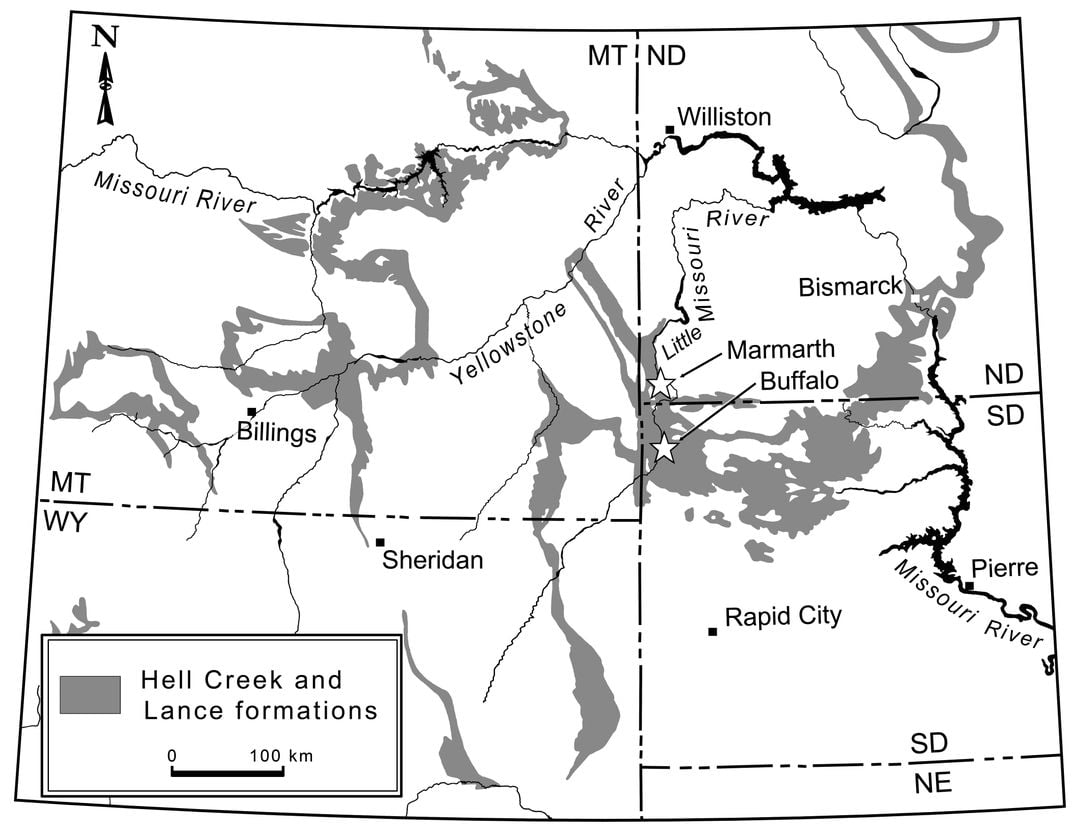

Some 66 million years ago, a feathered dinosaur with a toothless beak and a crested head roamed the stretch of mild, subtropical land that is today known as Montana, Wyoming and the Dakotas. A cross between a lizard and a chicken in appearance, its limbs were long and graceful and, counting its tail, it stretched to 11 feet in length. Despite an unassuming stature of just five feet, the dinosaur wasn’t without its defenses: Large, sharp claws tipped its forelimbs.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a5/46/a546540e-af29-43b3-af06-bdedbbd8db6e/lamanna_et_al_-_media_art_2_robert_walters.jpg)

The species, newly named Anzu wyliei and described by researchers at Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, the Carnegie Museum of Natural History and the University of Utah, belongs to Oviraptorosauria, a group of dinosaurs known for nearly a century from a few bits of fossilized bone in North America, but more substantial specimens from Asia.

“With the discovery of A. wyliei, we finally have the fossil evidence to show what this species looked like, and how it is related to other dinosaurs,” says Hans-Dieter Sues, curator of vertebrate paleontology at the National Museum of Natural History and a member of the team that published a paper on A. wyliei in PLOS One.

To reconstruct A. wyliei, the team analyzed three partial skeletons, all found in the fossil-rich Hell Creek Formation, a late Cretaceous rock deposit that was once a swampy forest.

Private collectors dug up two of the skeletons only 50 feet from one another in a portion of the formation in South Dakota, and they were later purchased by the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, where Sues, an expert in Oviraptorosauria, previously worked. The third Anzu skeleton was discovered by Tyler Lyson, now a post-doctorate at the Natural History Museum, who first sighted the bones as a teenager while exploring his uncle’s ranch in North Dakota.

In 2006, Lyson and Emma Schachner of the University of Utah attended a meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. There, they presented a poster describing their bones: three vertebrae, a radius, an ulna, a rib and a scapulocoracoid, a shoulder bone. While at the conference, they met Sues and Matthew Lamanna, the new paper’s lead author and assistant curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, who had been studying the two skeletons from the Carnegie Museum. Each had heard about the other group’s skeleton, and they were curious to compare notes to see if the similar-sounding fossils were related.

“It was quite clear that all three specimens belonged to the same new species,” says Sues. “So we suggested that we just pool our fossils and work on them as a team.”

It took the team eight years to reconstruct and study Anzu, creating a skeleton that was 75 to 80 percent complete. Along the way, the researchers came to some interesting conclusions: Because it had jaws that could cut and shear food but no teeth, Lyson and Sues assume it ate both animals and plants, and perhaps eggs. Two of the specimens had injuries. One a broken rib, and another an arthritic toe, which Lamanna says was probably “excruciatingly painful.” The two animals, he says, “led pretty rough lives.”

Paleontologists have long guessed that dinosaurs like Anzu existed in North America because of bits of bone found that resembled other Oviraptorosauria fossils known from Asia. In 1997, Sues published a paper that linked Oviraptorosauria jaw and hand specimens found in North America. But the specimens from Asia tended to be smaller and have shorter, fatter legs, as well as different beaks and lower jaws.

“We knew that there was a group of Oviraptorosaurs in North America, but we didn’t know many fundamental things about them,” Lamanna says. “What they looked like, how exactly they were related to their Asian cousins, how they lived, how big they got, all these things. Anzu helps to answer all of these questions.”

One question, however, that stymied Lamanna was what to name the creature. "It looks like a giant, scary bird," says Lamanna, who, along with colleagues, nicknamed it the ‘Chicken From Hell.’

"So I wanted to try to invoke that nickname in coming up with an official name for the animal, because I think it’s a pretty good description.” Lamanna eventually decided upon “Anzu,” a feathered demon from Mesopotamian mythology.

Anzu’s skeleton has solved some mysteries, but not all of them, says James Clark, a paleontologist at George Washington University who was not involved in the study. “They’ve got these weird heads, but the rest of the body doesn’t look much different than the Velociraptor,” a medium-sized predator with large, sickle-shaped toe claws, known from a few million years earlier in the late Cretaceous.

According to Sues, another potential A. wyliei skeleton was discovered in the Hell Creek Formation last summer. And unlike the recently reconstructed Anzu skeleton, this one includes a foot, which could offer new details.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Fawcett-Bio.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Fawcett-Bio.jpg)