Remembering 9/11, From a Scrawled Note to a Scrap of Fuselage

How objects both ordinary and extraordinary help us reflect on the devastation

Three months after the attacks of September 11, 2001, Congress officially charged the Smithsonian and the National Museum of American History with collecting and preserving artifacts that would tell the story of that day.

But where to start? If you were given the task, what objects would you collect?

Curators working at the attack sites were grappling with those questions. If they tried to collect the whole story, they would have quickly been overwhelmed. Instead they identified three points of focus to guide them: the attacks themselves, first responders and the recovery efforts.

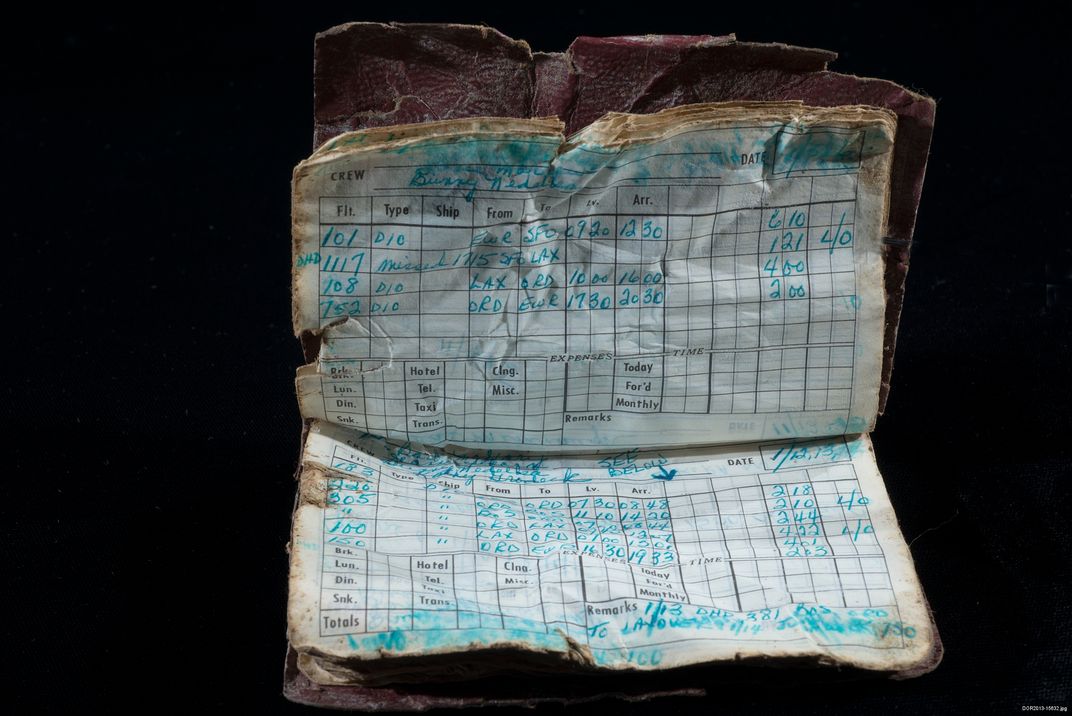

Fifteen years later, the collection includes more than a thousand photographs and hundreds of objects, among them memorials, thank you letters, pieces of the Pentagon, first responder uniforms from the World Trade Center, personal items such as wallets and clothing, Emergency Medical Technician equipment, parts of fire trucks and portions of the plane from United Flight 93 recovered from Shanksville, Pennsylvania.

The objects in the museum’s September 11 collection show both the ordinary and extraordinary moments in the midst of the devastation, reminding us of the chaos, the bravery, the loss and the unity that we all felt that horrifying day.

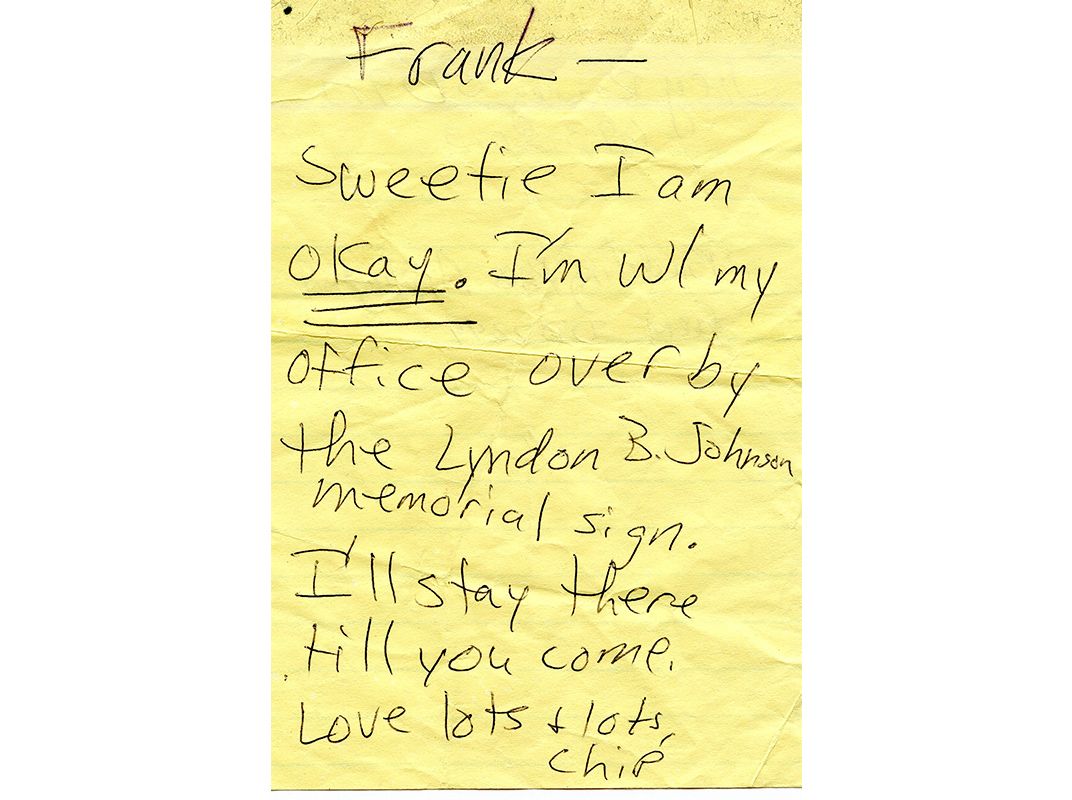

We see it in the handwritten note from Daria to Frank Galliard. Both worked at the Pentagon, and in the chaos after the attack, not knowing one another’s whereabouts or condition, they each separately made their way to a prearranged emergency meeting spot. Daria arrived first and scrawled a note in black pen on a scrap of yellow paper: “Sweetie I am okay,” the “okay” underlined three times. Frank did find Daria at their designated spot and the pair went on to assist a group of school children. (The museum offers more about the Galliard's touching story on its "Oh Say Can You See" blog.)

We see it in the hard hat of Dennis Quinn, an ironworker from Chicago who journeyed to New York to help clear debris. The skullguard-style helmet is practical—it’s designed to withstand high temperatures and is equipped with welder’s lugs. But it’s also personal—the owner’s name and union affiliation are carefully written in permanent black marker, surrounded by union and 9/11 stickers bearing the American flag, a bald eagle, and the statue of liberty.

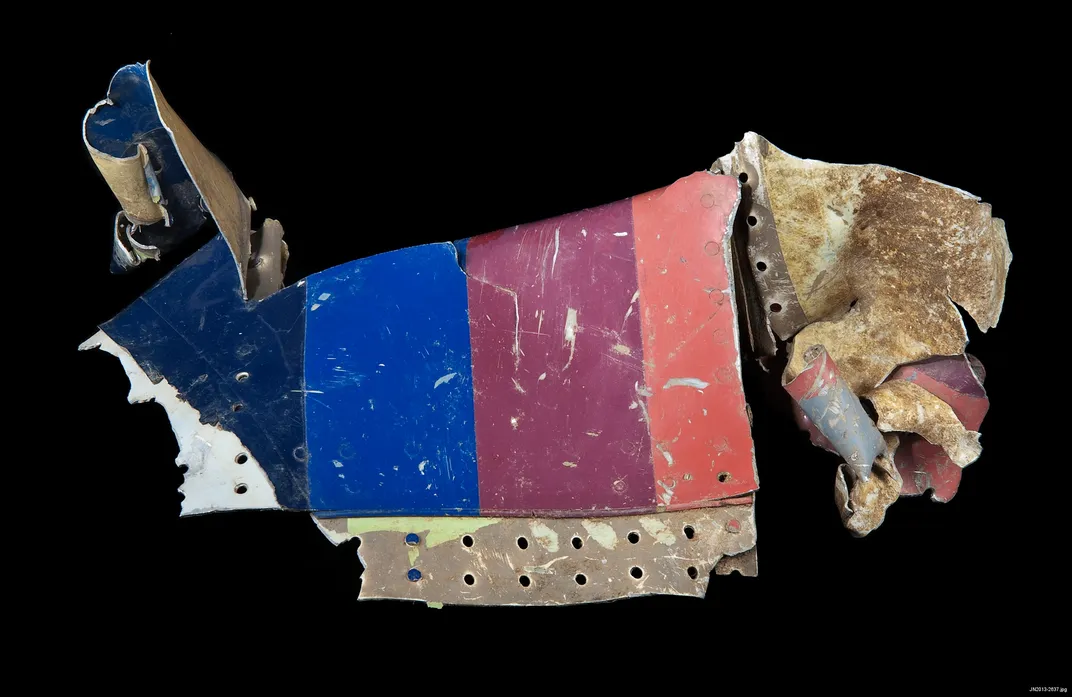

And we can see it in the twisted metal and scratched stripes of blue, pink, and orange in the fuselage of Flight 93, whose passengers and crew lost their lives fighting to ensure that no more buildings would be hit.

To commemorate September 11, the National Museum of American History is offering visitors the opportunity to interact and respond directly to select objects from our collections. The artifacts will be presented in an unmediated physical display, with no glass or casework between the visitors and the collection. We invite visitors to share their memories and thoughts, either in conversations with staff and other visitors, or by sharing through our Talkback boards, which provide the opportunity for written comments.

As historians, we continue to ask ourselves: How will Americans remember these events 25, 50 or 100 years from now? What questions will future generations ask? We can’t know for sure, but we do know that places like the American History Museum enable us to reflect on what it means to be a part of history, to contemplate how historic events affect our lives as individuals and as a nation.

On Sunday, September 11, 11 a.m. to 4 p.m., the National Museum of American History will observe the 15th anniversary of the September 11 attacks with a display of 35 objects from New York, the Pentagon and Shanksville, Pennsylvania, including airplane fragments, a World Trade Center stairwell sign and a Pentagon clock that stopped upon impact. Visitors can meet Robin Murphy, the inventor of a rescue robot used at Ground Zero and see a screening of the Smithsonian Channel’s award-winning documentary, 9/11: Stories in Fragments, based on the museum collections and featuring the perspectives of victims, witnesses, ordinary people and heroes from that fateful day.