The Remarkable Story of the World’s Rarest Stamp

The rarely seen, one-of-a-kind 1856 British Guiana One-Cent Magenta, which recently sold for a whopping $9.5 million, gets its public debut

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a0/6f/a06f1fad-e3fa-41b2-8f5f-683bdb9347b1/201466201mmweb.jpg)

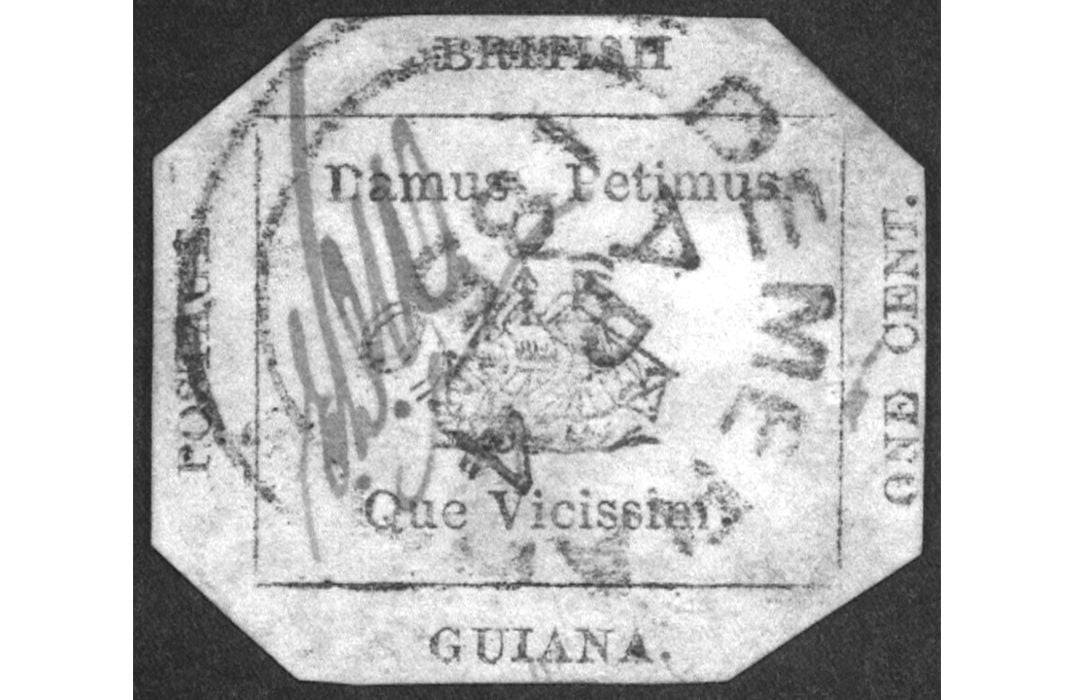

To see in person the 1856 British Guiana One-Cent Magenta—better known as “the rarest stamp in the world”—is a bit like looking at a red-wine stain or a receipt that’s been through the wash a few times.

The octagonal scrap of magenta paper, bearing a postmark and illustration of a three-masted ship, or barque, isn’t much to look at. But as the only known stamp of its kind, with a strange and peculiar origin story replete with colorful characters and record-breaking sales at auction, well, let us say that there is much more to this unspectacular stamp than meets the eye. Beginning today, the exhibit of the British Guiana One-Cent Magenta at the National Postal Museum in Washington, D.C. explores what the museum's chief curator of philately Daniel Piazza calls its "long, most interesting, circuitous history."

That history began in 1855, when just 5,000 of an expected 50,000 stamps arrived from Great Britain to its colony of British Guiana on the northern coast of South America. Shorted by 90 percent, the local postmaster found himself in a tough spot. If the colony's letters and newspapers were to be delivered, he was going to need some way to show the transaction of postage paid. So he decided to issue a provisional stamp to keep the mail moving until more postage could arrive from overseas. The only place that could create something with enough official cache to do the job in 1850s British Guiana was the local newspaper, the Royal Gazette.

Using moveable type, the printer of the Gazette produced a stock of one-cent stamps (for newspapers) and four-cent stamps (for letters), attempting to imitate the design of government-issued postage, adding a stock illustration of the ship and the colony’s Latin motto meaning “we give and we ask in return.”

“They were trying, very crudely and on a different type of press in the middle of the colony, as closely as they could to replicate the engraved stamps that were coming from Great Britain,” says Piazza.

The Gazette printer's admiral imitation worked and the postmaster moved quickly to remove them from circulation once they’d served their purpose (though Piazza cannot say exactly how long, he estimates they were in use about eight to 10 weeks). Since the one-cent stamps were used for newspapers, which few people saved, as opposed to the four-cent stamps used for letters, most disappeared shortly after their usage. The existence of the One-Cent Magenta would likely have been forgotten altogether had it not been for a 12-year-old Scottish boy named Vernon Vaughan, living in British Guiana, who found one odd stamp among his uncle’s papers in 1873. By this time the stamp had been postmarked and initialed by a local postal clerk (a common practice at the time to discourage counterfeiters), and appeared well used. The peculiar stamp hardly struck the boy as very valuable, so the budding philatelist soon sold it for a less-than-princely six shillings (about $10 in today’s dollars) and bought a packet of foreign stamps that he apparently found more aesthetically appealing. Thus began the decades-long, cross-continental journey of the One-Cent Magenta.

After that initial sale, the stamp was picked up then passed along from one collector to the next before it was spotted in 1878 by Count Philippe la Renotière von Ferrary, who was the owner of what has been called the most complete worldwide stamp collection ever to exist. Arguably the greatest stamp collector in history, Ferrary would have known how unusual the stamp was as soon as he saw it, so he snatched it up in a private sale. As more was learned of the stamp’s provenance, it grew to become a prized item in Ferrary’s collection, which upon his death in 1917, was donated to Berlin’s postal museum.

Following the World War I, the count’s collection and the One-Cent Magenta was seized by France as part of its war reparations. From there it passed to New York textile magnate and renowned stamp collector Arthur Hind, then to Australian engineer Frederick T. Small, and then to a consortium run by Pennsylvania stamp dealer Irwin Weinberg.

Its most recent owner, who bought the stamp in 1980, was John E. du Pont, the chemical company heir, wrestling enthusiast, and murderer portrayed by Steve Carell in last year’s Oscar-nominated Foxcatcher. Before becoming interested in amateur wrestling, du Pont was a passionate philatelist, and paid $935,000 for the One-Cent Magenta, purchasing it from Weinberg at auction in 1980. Following du Pont’s 2010 death in prison, it was put up for sale at auction and sold last summer for $9.5 million—four times more than any other single stamp has ever fetched.

This recent sale helps explain the timing of the Postal Museum exhibition.

Over the years, the curators at the museum have tried repeatedly to put the stamp on display, only to be turned down. But ahead of the One-Cent Magenta’s latest auction, representatives for Sotheby’s reached out to the museum. They sought to use some of its scientific equipment, developed in the decades since the stamp’s previous sale, in order to examine elements of the item and to verify its authenticity.

After granting this access, the Smithsonian left a request with Sotheby’s to alert the auction’s winners of the Institution’s interest in displaying the stamp. The new owner—shoe designer Stuart Weitzman—after discussions with the museum, agreed to an unprecedented three-year loan.

This was quite a coup. Piazza estimates that of the almost 140 years since being discovered, the One-Cent Magenta has been on view for a period of less than a month. And philatelists the world over have yearned to see it.

“The last time I saw the stamp was I think in 1986 at the International Stamp Show in Chicago,” says Ken Martin, executive director of the American Philatelic Society, who is eager to see it when it finally goes on display.

He adds that he also expects the exhibit to help raise interest more generally in the National Postal Museum and stamp collecting more generally.

“Even collectors who are well versed in this story have not seen the stamp in 35 years,” Piazza adds, referring to a brief showing in 1987. And this exhibit, like the few earlier showings, lasted only a few days, and took place at an exclusive stamp show closed to the public. The last and only time a non-philatelic audience got a look at the stamp was at the World’s Fair in New York City—in 1940.

The stamp’s strange history is detailed in the exhibit, held in the museum’s William H. Gross Stamp Gallery. Its physical elements will also be examined, including what was recently learned about the stamp using the museum’s cutting-edge “forensic philately” tools. For example, using special florescent lights filtered out the surface coloring, getting a clear view of the black ink below the magenta and any alterations made to the stamp after its printing. This allowed the Smithsonian to confirm that this is indeed the one-of-a-kind One-Cent Magenta, not one of the less rare four-cent versions that could have been altered to look like a one-cent.

“Any alteration or change to the front of the stamp would floresce differently when looking at it under different light fixtures,” says Piazza.

An infrared filter allowed the Smithsonian's curators to better reveal markings made on the stamp over its journey of more than a century and a half. Among these are a postmark of April 5, 1856 (reading "Demerara," a county in British Guiana); the handwritten initials "E.D.W." from postal clerk Edmond D. Wight (officials often made such marks at the time in an effort to discourage counterfeiting); and the inscriptions of "British | Guiana" and "Postage | One Cent."

Also on exhibit will be something that has never been displayed before: the back of the stamp. Visitors will see a number of “owner’s marks” that reveal the different collections through which it has passed.

“There’s an interesting layering that visitors will be able to see that could potentially be attributed to a wife [of one collector] trying to obliterate the owner’s mark of the husband, so there’s some interesting intrigue,” says Sharon Klotz, director of exhibitions for the museum, who planned how best to display this artifact. “Our goal is to anticipate questions a general audience might have,” while still appealing to expert philatelists.

She adds that “the authenticity of the view—as naked and true as possible—is incredibly valuable.”

The exhibition "The British Guiana Once-Cent Magenta: The World's Most Famous Stamp" is on view at the National Postal Museum from June 4, 2015 through November, 2017 in the museum's William H. Gross Stamp Gallery. The stamp will not be on view, however, November 27 through December 10, 2015 and May 23 through June 10, 2016. Additionally, the stamp may need to be removed on occasion for conservation, so the museum suggests calling in advance 202-633-5555 to confirm availability.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)