Smithsonian Researchers Uncover Extinct, Ancient River Dolphin Fossil Hiding in Their Own Collections

Sometimes, paleontologists don’t have to go into the field to discover a tantalizing new species

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/15/66/1566b65c-60d8-42d2-82d2-bf88dc6843fd/nhb201600327web.jpg)

More than 60 years ago, while mapping what would eventually become the Yakutat City and Borough of Alaska, a USGS geologist named Donald J. Miller stumbled across an ancient skull. The snout had been broken off, but the preserved portion left no question that the cranium belonged to a prehistoric dolphin. From Alaska, the skull went to the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History, where it hid its secret until new research revealed the fossil for what it really was.

As Smithsonian paleontologists Alexandra Boersma and Nicholas Pyenson announce today, what Miller had found was a species previously undiscovered by science.

“It’s a lovely skull, which is probably the first thing I noticed about it,” Boersma says. It was immediately clear to her that the dolphin was a relative of a rare species alive today. The South Asian River dolphin, which includes the Gangus and Indus river dolphins, is an endangered species that makes its home in three river systems of Southeast Asia today, but in the deep past the relatives of this rare cetacean lived at sea.

These are called platanistoids. The skull Miller found appeared to be a relative of this strange mammal. The discovery was all the more exciting, Boersma says, “because it could answer questions about how this once cosmopolitan group dating back over 20 million years dwindled down to one freshwater particular.”

The fossil's prodigious age also made it stand out. “The archival notes with the specimen stated that it was found in Alaska, and that it was very old for a dolphin,” Pyenson says, living during a time period called the Oligocene and the details of whale evolution during this span are still murky. This made the skull Miller found one of the oldest dolphins, not to mention that it is the northernmost find of its type to date. And it turned out to be a species and genus never before seen by scientists.

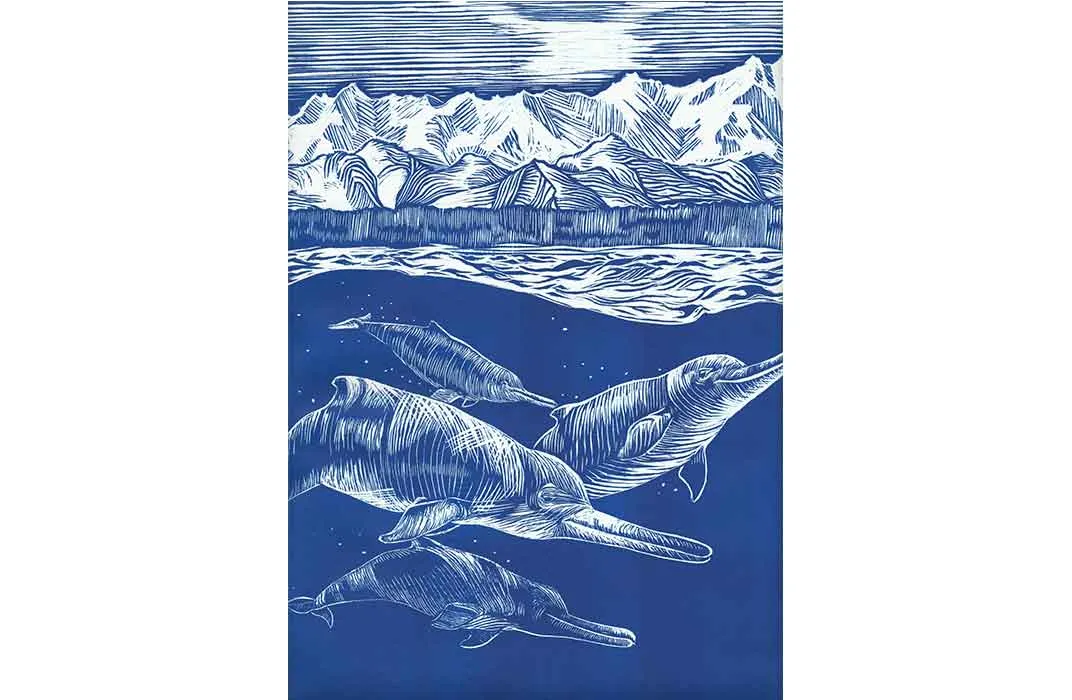

Dating to 29 to 24 million years old, Boersma and Pyenson named the dolphin Arktocara yakataga today in the journal PeerJ. Yakataga is the Tlingit name of the region where the fossil was found and arktocara is a Latin word meaning the “face of the north.” The fossil was also digitized (above) and made available as a 3D model.

Despite being a relative of a living river dolphin, Arktocara lived at sea. “It’s not always a sure bet that cetaceans die where they live,” Pyenson says, “but we think it’s fair to say that Arktocara was likely a coastal and ocean-going species” that was about the size of a modern bottlenose dolphin. While the details of what Arktocara ate and how it lived await future discoveries, Pyenson expects that it was similar to today’s Dall’s porpoises.

Given that fossil dolphins related to the platanistoids have been found from Japan to California to Washington, it’s not a shock to find one popping up in the rock of Alaska, says College of Charleston paleontologist Robert Boessenecker, who was not involved in this study. He adds that studies have found that these ancient forms might not be related to today’s South Asian River Dolphin, but might be more archaic branches that fizzled out.

Still regarding the Alaska location where the specimen was found, Boessenecker notes that “high latitude fossil records of marine mammals are unfortunately quite limited,” perhaps because they haven’t been extensively searched, and so more “field studies should absolutely be directed towards further examining this site.”

For now, though, Boersma notes that there’s much still to discover in museum collections. Not all new fossil species are fresh from the field. Some, like Arktocara, have been hiding among the shelves for years. “All the time, we find new things in the collections that answer old questions,” Boersma says. Now, she and Pyenson are on the lookout for more that might fill out that backstory of today’s strange South Asian River Dolphin.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)