New Jamestown Discovery Reveals the Identities of Four Prominent Settlers

The findings by Smithsonian scientists dig up the dynamics of daily life in the first permanent British settlement in the colonies

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/57/6a/576a0319-b55a-4259-b114-dc9e429bd798/sep2015_j03_jamestown.jpg)

One of the bodies was just 5 feet 5 inches long, and missing its hands, most likely from four centuries of deterioration. It had been jostled during burial, so the head and shoulders were scrunched long before the wooden coffin lid and the weight of the dirt above had collapsed on it. Flesh no longer held the jaw shut; when this skeleton was brushed free late in 2013, it looked unhinged, as if it were howling. The bones, now labeled 3046C, belonged to a man who had come to the New World on the first trio of ships from England to the spot called Fort James, James Cittie or, as we know it, Jamestown. He survived the first wave of deaths that followed the Englishmen’s arrival in May of 1607. Over the next two years, he conspired to take down one leader and kill another. This man had a murderous streak. He died, along with hundreds of settlers—most of the colony—during the seven-month disaster known as the "starving time".

Jamestown’s original fort is perhaps the most archaeologically fertile acre in the United States. In 1994, Bill Kelso, a former head archaeologist at Monticello, put his shovel in the clay soil here and began unearthing the first of two million artifacts from the early days of the settlement. His discoveries, all part of a project known as Jamestown Rediscovery, include everything from full-body armor, a loaded pistol and a pirate’s grappling pike to children’s shoes and tools from such a broad array of trades (blacksmith, gunsmith, mason, barber, carpenter, tailor and more) that it is clearly a myth that the settlers arrived unprepared. One firecracker revelation after another is now filling in the history of the first successful English colony in America. Kelso and his team captured international attention two years ago when they reported finding the butchered remains of a teenage girl, clear evidence that the settlers cannibalized their dead to survive during the famine. The team named the girl “Jane” and, along with Doug Owsley and the forensic anthropology lab at Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, reconstructed her skull and digitally recreated her face, thus populating this early dark chapter in American history. In another major find, a few years back, the team uncovered the foundation of the fort’s original church, built in 1608—the earliest known Protestant church in the Americas, where Pocahontas married Virginia’s first tobacco farmer, John Rolfe, and brought the warring natives and settlers to a temporary truce.

This was where 3046C was laid to rest, in the winter of 1609-10. In spite of being under siege, and with food so scarce they were scavenging rats and cats and gnawing shoe leather and even, on occasion, their dead, his fellow settlers gave him a fine burial in the church’s chancel. A hexagonal oak coffin was made for him, a captain’s staff put alongside him. Just before the dirt sealed him off for centuries, someone placed a small silver box on top of his coffin. When the archaeologist lifted it out of the trench and gave it a tentative shake, the corroded box rattled.

Three more skeletons, labeled 2993B, 2992C and 170C, have been pulled from beneath the chancel. All date to around the same time as 3046C, and though one was in a simple shroud, the other two also had splendid coffins. Who were these men? Why were they buried, not in nearby fields with the other settlers, but beneath the floor of the church’s altar? Kelso and Owsley have marshaled an army of experts who have dedicated thousands of hours of scientific and archival scrutiny to the task of matching the remains with the historic record. Now they are ready to unveil the identities of these latest Jamestown discoveries. Each has its part in the larger story of life on the edge of a New World.

**********

On a chilly gray day in late April, Kelso urged me out of the headquarters of Jamestown Rediscovery and past the house behind the hedges where he and his wife live; I needed to see the whole site before the skies opened and drenched us. Unspoiled so far by commercial development and buffered by National Park Service land, the 22.5 acres purchased by the nonprofit Preservation Virginia in the early 1890s are dominated by monuments: an obelisk, a statue of Pocahontas and another of explorer John Smith, and a weathered replica of a brick chapel that eventually replaced the original church. They give weight to the landscape around Jamestown’s original fort. The native tribes had laughed at the first Englishmen’s choice of real estate. Who wanted to live in a swampland with no fresh water? But it’s a beautiful spot, on a channel deep enough for multimasted ships yet far enough up the James River that its residents could anticipate attacks from their Spanish enemies.

Jamestown was England’s attempt to play catch-up with the Spaniards, who had enriched themselves spectacularly with their colonies in South America and were spreading Catholicism through the world. After years of war with the Spanish, financed in part by pirating their ships, England turned to the Virginia Company to launch new colonial adventures. The first 104 settlers, all men and boys (women didn’t arrive until the next year), sailed with a charter from their king and a mission to find silver and gold and a passage to the Far East. They landed in Jamestown, prepared to scout and mine the land and trade with the native people for food. And they did trade, exchanging copper for corn between eruptions of hostility. But as Jamestown’s third winter approached, the Powhatan had limited supplies of corn; a drought was smothering their crops and diverting the once plentiful giant sturgeons that fed them. When English resupply ships were delayed, and the settlers’ attempts to seize corn turned violent, the Powhatan surrounded the fort and killed anyone who ventured out. Brackish drinking water, brutal cold and the lack of food did their damage from within. Jamestown’s early history is so dire it’s easy to forget that it endured to become a success and the home of the first democratic assembly in the Americas—all before any pilgrims made camp in Plymouth. Abandoned in 1699 when Virginia’s capital moved to Williamsburg, the colony was thought to have sunk into the river and been lost. The first archaeologist who brought skepticism to that story, along with a stubborn determination to test it, was Kelso.

He stopped by the current excavation site and introduced me to the begrimed crew toiling in the bottom of a pit six feet deep. The archaeological work here has a temporary feel among the monuments. Visitors are separated from the excavations by a simple rope because Kelso wants the public to share in the discoveries. Nearby, the location of an early barracks has been roughed out with lengths of saplings. Kelso has unearthed foundations that hint at the class lines imported from England: row houses built for the governor and his councilors, as well as shallow pits near the fort wall where laborers probably improvised shelters. “We’re trying to reconstruct the landscape,” Kelso says. “It’s a stage setting, but it’s in pieces and the script has been torn up.” He found a major piece when he located the fort’s original church. It was large, more than 60 feet long, the center of life for all the settlers in its day. John Smith called it the “golden church” because, though its walls were mud mixed with black rushes and its roof thatched, two broad windows filled it with light and it was crowned with two bells. Kelso’s team has outlined the foundation with a low uneven wall using the same mud-and-stud construction the settlers would have used to make their first buildings. Four stark iron crosses mark the places where the chancel bodies lay. Each received a distinct number; a letter identified the layer of dirt in which the body was found. Kelso stood by their resting places, now covered with crab grass and clover, as the sky darkened, a battered leather hat over his white hair.

He nodded toward the first cross, which marked the burial of 2993B, the one laid to rest in only a shroud. “Robert Hunt, the minister, was the first buried here. He came with the original settlers in 1607,” Kelso said. That first fleet to Virginia had been delayed by storms and stuck within sight of the village of Reculver in Kent, where Hunt was from, for six weeks in heavy seas—six weeks! Hunt, who from the ship would have been able to see the spires of a church he knew well, was so ill that the others considered tossing him overboard. He had already said goodbye to his two children and quit the young wife he suspected of infidelity. He’d defended himself from accusations of an affair with his servant woman. He had made his will and turned his back on England. He would get to the New World if it killed him.

A slight and strong-willed man, Hunt delivered sermons and personal appeals to keep the peace among the leaders, whose clashes and quarrels fill the narrative history of Jamestown. In early 1608, a fire raged through Fort James, destroying all of Hunt’s possessions, including his precious library of books. The fire might have been set accidentally by sailors who had arrived in the bitter month of January. Hunt did not complain (as John Smith wrote, “none never heard him repine”). The mariners were put to work rebuilding a storehouse and a kitchen and, while they were at it, constructing the future wedding church of Pocahontas. Hunt, who had been presiding over services outside under a stretched sail, must have taken consolation in seeing its walls go up. He died, probably of disease, within weeks of its completion.

See a 3D rendering of Robert Hunt's (2993B) grave:

A flock of children in matching red slickers surrounded us as the drizzle began. Two girls dragged their friend to stand by the chancel like Pocahontas at her wedding. One hovered, tightly sprung, by Kelso’s side; she was dying to tell him that she wanted to be an archaeologist. Kelso, age 74 and a grandfather of four, recognized her intensity. “Study hard,” he told her, “and don’t let anyone talk you out of it.”

All through the site, I noticed tombs and grave markers, a granite cross and dozens more of those black iron ones, evidence of the price paid by the colonists. I asked Kelso how many burials there are in Jamestown and he pulled out a map dense with tiny maroon rectangles. He started pointing them out, dozens on the side of the brick chapel and who knew how many inside...a trench with 15 burials near a cellar they’re digging now...scores on the way to the visitors’ café and beneath the elevated archaeology museum. Kelso’s finger stopped by the far eastern border of the fort. “There don’t seem to be any here,” he said. Where are the bodies in Jamestown? It is easier to say where there are none.

**********

James Horn, a British-born historian of the early colonies and president of Jamestown Rediscovery, explained to me the importance of religion to this tale, particularly England’s desire to make Jamestown a base for the spread of Protestantism. “Pocahontas was a conversion story!” Horn said as Kelso and six or seven younger archaeologists and conservators gathered in Horn’s office. They lowered the shades so they could present the discoveries that they had kept secret for more than a year. There was intense excitement, but the researchers took time to apologize before showing me photos of the skeletons. They are aware of how sensitive this type of work is. They are excavating graves after all. State historic preservation officers must be involved and satisfied that there is a scientific reason for the disturbance. And though the researchers invite the public to stand at the edge of the excavations, a fence goes up as soon as human remains are involved. They try to convey respect at every stage of unearthing and testing.

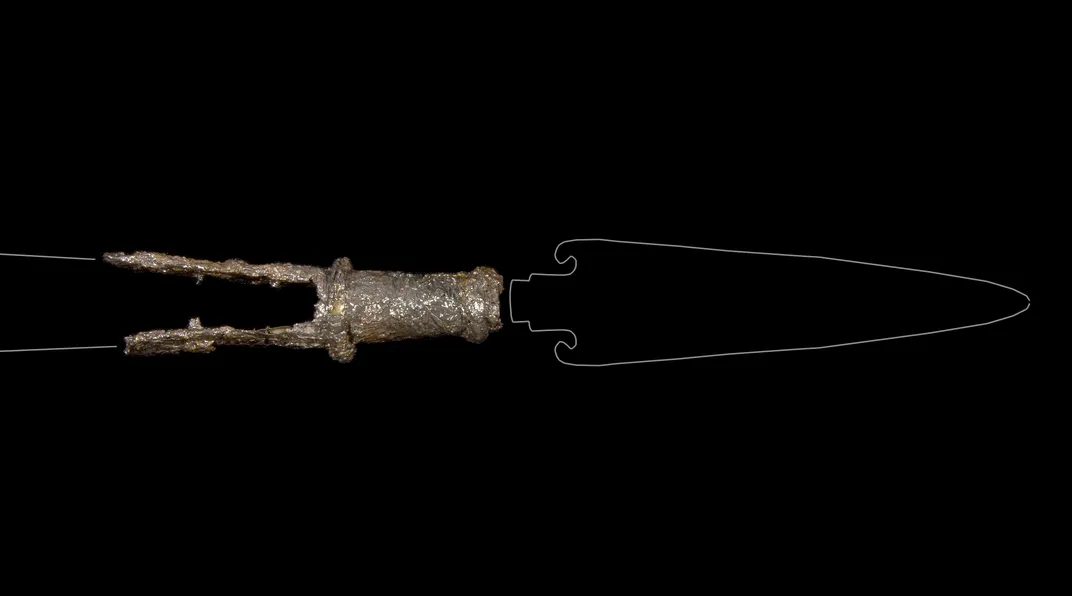

A screen lit up with a sequence of X-rays and CT scans of the “grave goods,” the objects found with the best-preserved of the bodies, 3046C, now identified as Captain Gabriel Archer. Typically in English graves of this period only royalty were buried with such goods, but Archer boasted two. The captain’s staff was a sign of leadership. The mysterious silver box appeared to have religious significance.

Archer was a gentleman who trained as a lawyer, but he might be better characterized as a provocateur. He had been shot in both hands with arrows by Native Americans on the day the first ships arrived in Virginia, the same day he learned that, in spite of his connections and high status and experience, including a previous expedition to New England, he had not been appointed to the colony’s ruling council. John Smith, a soldier and the blunt son of a farmer, had. Their enmity was sealed, one of many “struggles between alphas,” as Horn described it. The two men disagreed about whether Jamestown was the right spot for the colony (Archer said no) and how to wield power (Smith had no use for councils). They were alike in their belligerence. Archer helped unseat the first president of Jamestown, who branded him a “ringleader...always hatching of some mutiny.” Smith had been in chains at least once on mutiny charges too.

See a 3D rendering of Gabriel Archer's (3046C) grave:

When Archer finally secured a leadership position as the colony’s official record-keeper, he used it to try to hang Smith. Archer called Smith’s loyalty into question after two of Smith’s scouts were killed in a skirmish with the natives; Smith was taken captive in the same incident, but returned unharmed. When this plot failed, Archer attempted murder, detonating Smith’s pouch of gunpowder while he slept—so historians and Smith himself believed. Smith headed back to England, where he made a surprising recovery and wrote the accounts that figure so prominently in American history, including the story, perhaps apocryphal, of his rescue from death by the young Pocahontas. He became the best known of all the Jamestown leaders. Archer died soon after the attempt on Smith’s life, from the bloody flux (dysentery) or typhus or starvation.

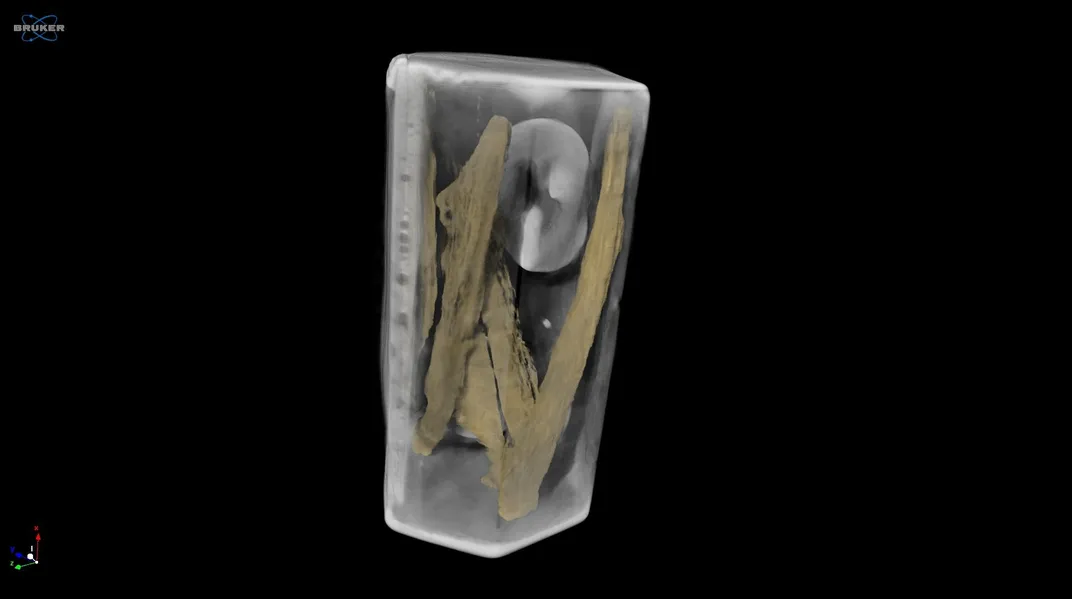

Kelso projected a short video of Jamie May, a senior archaeologist, lifting the silver box out of Archer’s grave. “Feels like there’s something in it!” she said, shaking it. After conservationists spent more than 100 hours carefully removing corrosion with a scalpel under a microscope and polishing and degreasing its surface, the silver-copper alloy still looked battered, but a crude initial, M or W, could be seen on one side, and on the other, what looked like the fletching of an arrow. What was inside? Incredibly, the archaeologists have decided not to open the box. It is so fragile, they fear it would crumble to pieces. Instead they are using every scientific trick to glimpse its interior.

I was scribbling in my notebook when Kelso said, “Wait, she’s not looking,” and the researchers backed up the slide show to a high-resolution, noninvasive micro-CT scan of the box’s contents: two pieces of a lead object—possibly a broken ampulla, a vessel to hold holy water—and several small pieces of bone. “Human? We don’t know. The best we can figure is mammal,” said Michael Lavin, a conservator. Only 41 years old, Lavin, like several others on the team, has spent his entire career with Jamestown Rediscovery. “We think it’s a reliquary,” a container for holy objects, perhaps a Catholic artifact.

But hadn’t Catholicism been banished in England? Weren’t they all Anglicans? Yes, Horn pointed out, but there were still Catholics practicing underground. Rosary beads, medallions of saints and a crucifix carved on jet have also turned up at Jamestown. Gabriel Archer’s father was among the Catholics, called a “recusant” and cited in court for failing to attend Anglican services. Archer had learned resistance at home.

And was that an M or a W inscribed on the silver box? A Smithsonian expert in microscopy scrutinized the etching and showed that the letter had been formed using four distinct down strokes. It was probably an M. One of Archer’s co-conspirators in his effort to kill John Smith had been named John Martin. Was it his silver box etched with the archer’s arrow and left on Archer’s coffin? Was it a token of sentiment, or of defiance?

The archaeologists here find themselves at a particular moment when the artifacts can still be recovered and the technology has advanced sufficiently to extract important information. The window for scrutiny is closing, though, as the skeletons still buried deteriorate and as changing climate lifts the waters of the James River. “These bones were almost gone,” Kelso said. How long will it be before this site is completely swamped?

**********

After Gabriel Archer died, along with most of the rest of the colonists, Jamestown came close to collapse. Survivors, so skeletal they looked, as one witness wrote, like “anatomies,” were in the act of abandoning the fort in 1610 when orders from the new governor, arriving in June with a year’s worth of food and hundreds of men, turned them back. Thomas West, known as Lord De La Warr (Delaware was named for him), marched in with a force of halberd-bearing soldiers, read his orders in the golden church, then immediately began to clean up the squalor from the Starving Time. He had two valued deputies in this mission to revive the colony, his knighted cousin, Sir Ferdinando Wainman, and a younger uncle, Capt. William West. The relatives helped establish martial law and enforce discipline, including mandatory church attendance twice a day, and Wainman (also spelled Weyman and Wenman, among others) was given the additional responsibility in the newly militarized colony of Master of Ordnance.

Even connections and privilege and sufficient food could not protect these men from the dangers of the New World: Wainman died his first summer, probably of disease. His death was, according to one leader in the colony, “much lamented” because he was “both an honest and valiant gentleman.” His skeleton, 2992C, was found between those of Hunt and Archer. Genealogical research, conducted by Ancestry.com, reveals that Wainman had an infant daughter in England, whose christening records list multiple noble godparents. The knight had invested 100 pounds in the Virginia Company, hoping to multiply it on his adventures. When he died, Lord De La Warr saw that the stake was given to Wainman’s child.

See a 3D rendering of Sir Ferdinando Wainman's (2992C) grave:

West, only in his 20s, was killed later that year by Native Americans almost 50 miles upriver, and his body brought, with difficulty and sorrow, back to the church for burial. A close examination of West’s ribcage revealed silver threads from a bullion fringe, which would have decorated a sword or royal sash. His skeleton, 170C, suffered the most damage over the centuries. During the Civil War, the land had been scraped to build a fort, narrowly missing the bodies, but a utility line dug in the late 1930s took part of 170C’s skull.

See a 3D rendering of Captain William West's (170c) grave:

“Jamestown is a story of luck, figuratively and literally. Over and over, lost and rediscovered, lost and saved,” said Kari Bruwelheide, a forensic anthropologist at the Smithsonian Natural History Museum, where I met her in an office with a cabinet lined with skulls. Bruwelheide noted one important way that archaeology had contributed to saving the site: High-density scans of the chancel remains had been made before excavation. “Someday, you’ll be able to visit this site virtually.”

But what the scientists still don’t know about the four bodies continues to tease them. “Not a one do we have a [forensic] cause of death for,” Doug Owsley told me. Owsley, the prominent forensics expert who has worked on human remains from the controversial prehistoric Kennewick Man to 9/11 and beyond, was leading me through the warren of anthropology offices and down increasingly narrow halls. He inserted a key to a locked door, and admitted me to the layout room, where every surface, including the shelves of what looked like commercial kitchen serving carts, was arrayed with human bones. He pulled two chairs up beside a skeleton from Maryland set out as part of his long-term project, an exploration of what it means to become an American through burials and bones from the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. He and his team have data on more than a thousand skeletons from burial sites throughout the Chesapeake region (most of these remains were threatened by erosion or development). By looking at burial practices and the chemical composition and shape of bones and teeth, the researchers can learn much about a person’s life. They can tell whether a woman sewed from marks in the teeth left from biting down on thread.

I set my coffee near the ribs while Owsley reflected on the De La Warr relatives, whose remains were nearby. They had the forensic marks of wealth for the period: high lead counts, which came from eating off pewter or lead-glazed dishware. “The lead levels tell us these are somebodies,” Owsley said. Neither the knight nor the young captain showed the dramatic development of muscle attachments common to people involved in heavy physical labor. Wainman did have pronounced ridges on his leg bones, suggesting greater use of leg muscles, perhaps from horseback riding. Readings of oxygen isotopes, accumulated in the bones from drinking water, suggest that all the men, including Hunt and Archer, were from the southern coastal regions of England. Of the three coffins, one had been hexagonal and two cut in at the shoulders and squared tight around the head. These two anthropoid coffins, which held the De La Warr relatives, fascinated Owsley. King James had been buried in such a coffin, which required a skilled craftsperson to build, and Owsley has seen only one other from this period in North America. “Did you see the three-dimensional picture of the coffin nails? Remarkable,” Owsley said. Because the wood in the coffins had decayed, only the nails remained in the dirt around the skeletons, but Dave Givens, an archaeologist and specialist in geographic information systems, had mapped their locations, marking their depth and orientation, then plotting them in a 3-D image. The nails seemed to float in space, clearly outlining the shapes of the coffins.

Strapping on a headband with a portable microscope and a light, Owsley pulled out a tray of jawbones from the chancel burials. “I’m re-editing my field notes, checking teeth to verify which sides the cavities are on,” Owsley said. He explained that the longer the settlers had been in the colonies, the more decay you could see—the difference between the European diet based on wheat and the more destructive one based on the New World staple, corn. “And see?” he said, showing me the jaw with noticeably less-worn teeth. “Our young fellow [West] had one cavity. He was pretty new off the boat.” Luckily his mandible had not been in the line of the utility trench. “I’d love to have his cranium, though,” Owsley said. He picked up 2993B, “our older man [Hunt], the minister, who would have been 35 to 40. See that tiny dark speck in the tooth there? That’s a break in the pulp. It was abscessing. That would have been weighing him down.” He set it aside and picked up Archer’s jawbones. “Now look at this: cavity, cavity, cavity, more cavities, 14 in all, teeth with enamel completely worn, a destroyed crown, broken exposed pulp chamber, two active abscesses. This guy was in agony. John Smith had returned to England after the attempt on his life because there was no surgeon at Jamestown to see to his burns, so we know there was no medical person around to pull this man’s teeth.” I remembered that when the archaeologists uncovered him, Archer looked like he was howling.

So Owsley and his team chip away at the mysteries of the four Jamestown leaders buried with honor. The goal is to extract bits of factual evidence to piece together a larger picture, while still preserving the scientific data and guaranteeing access to it in the coming years. What we are learning now deepens our understanding of the force of religion in the early settlement, the fractious nature of leadership and how people of wealth and privilege were mourned in the wake of those great levelers, suffering and death. “Students of the future will have questions we haven’t thought of,” Owsley said.

**********

In Jamestown, the rain fell gently as we gathered by the obelisk. The half-dozen or so archaeologists here take turns leading tours. Danny Schmidt, who started in 1994 as a high-school volunteer and is now a senior archaeologist and field manager, shepherded us to the current excavation pit, where two archaeologists were hard at work with brushes and dustpans in what appeared to be a massive cellar. Then he led us to the excavation of another cellar—the one used for trash from the "starving time". “This was where we found butchered dogs and horses, a human tibia, and a few days later, most of a human cranium. Right away, we could see it had marks like those on the bones of the dogs. They belonged to a 14-year-old girl we called Jane.”

Schmidt pointed out the steps constructed for Queen Elizabeth II, so she could walk down into one of the pits. She visited Jamestown for its 350th anniversary and returned in 2007 for its 400th. Of course she is fascinated by the site. This is the birthplace of modern America and, as one of the earliest British colonies, a nursery for the empire.

Schmidt turned to the foundation of the original church, “the great-grandfather of 10,000 Protestant churches,” as he put it, now marked out with rough mud walls. “Yes, Pocahontas was married here, but not John Smith,” Schmidt said wryly. Pocahontas changed her name to Rebecca and bore a son with John Rolfe. The marriage brought seven years of peace between the Powhatan and the English and culminated in a celebrated voyage to England. But the peace ended with Pocahontas’ death as she was departing for the trip home, and she was buried in England.

Nearby, the reproduction of the brick chapel offered temporary shelter from the drizzle. The rigid class lines of English society had bent in this colony where resourcefulness and mere survivorship mattered as much as connections, and in 1619, the first elected assembly of the Americas met here. This was also where Schmidt was married, he told us. Standing on its brick floor, I pictured ghosts in ruff collars smiling down on him and his bride.

The tour ended near a shrine to Robert Hunt, though Schmidt didn’t mention the discovery of Hunt’s body (the news had not yet been made public). A knot of history lovers surrounded Schmidt, asking questions. I noticed his pocket vibrating and his hand reaching in to silence his phone. Finally, one of the archaeological team approached and caught Schmidt’s eye. “They found something?” Schmidt asked. Yes, they had.

We hurried past the 1607 burial grounds and Jane’s cellar to the current pit. Schmidt waved me behind the rope and, electrified, I stood with Kelso and Horn and the others while, from the bottom of the excavation, a field archaeologist named Mary Anna Richardson passed up a tray of loose brass tacks. “We kept finding these, and now it seems we’ve found a bunch in a pattern—maybe a decoration for the lid of a wooden box or a book?” The mood was festive, and someone showed the tray of stray tacks to the small crowd gathered on the other side of the ropes. America, still being discovered!

Mike Lavin, the conservator, coached Richardson on how to protect the surviving wood with its pattern of tacks for the night: “Cover it lightly with soil, then upend two dustpans. We’ll pedestal it and lift the whole thing out tomorrow.” The rain was coming down steadily, and those who had hurried over from the offices and lab shared umbrellas while the archaeologists covered the pit with tarps. Horn grinned, his nice leather shoes spattered with mud. No one wanted to leave the place that so frequently delivered news of the people who founded a colony in a swamp and seeded a country with desperation and hope.

I mentioned Schmidt’s marriage in the brick chapel to Kelso—what a fitting perk for those who toiled in the graves and garbage pits of Jamestown, to celebrate life on the site of the second historic church, the one with a roof and pews. Lavin looked up. “That’s where I got married,” he said. “Me, too,” an archaeologist added, and another said, “I think we all did.”

Richardson wiped her hands on her jeans: “And I’ll be getting married there in September.”

Related Reads

Jamestown, the Buried Truth