Landscape Through a Car Window, Darkly

A new exhibition presents 1970s photography that challenged the traditional American landscape

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130802110035mayes_cr.jpg)

By happy coincidence, the new American Art exhibition, “Landscapes in Passing,” is located down the hall from an 1868 painting by Albert Bierstadt—a lush, majestic panorama of the untouched American wilderness, and what most people have in mind when they hear the word “landscape.”

“Landscapes in Passing” brings together the work of three artists who challenged this canonical view in the 1970s. Inspired by the interstate highway system, photographers Elaine Mayes, Steve Fitch and Robbert Flick dared to look past the overweening grandeur of landscapes past, to explore the transient, auto-mediated way we see nature in the present.

The earliest series in the exhibition, Elaine Mayes’ Autolandscapes (1971), captures the view from a car window. Mayes drove from California to Massachusetts, snapping a photograph every time the landscape changed. From a moving car, the road, horizon line and variations of terrain are abstracted to bands of black, white and gray. “She wanted to capture her experience of moving through the space and how the landscape changes from urban to rural to somewhere in between,” says curator Lisa Hostetler. In the gallery, the series is displayed sequentially and unfolds like a zoetrope, with a strong horizontal through-line conveying speed and motion.

Steve Fitch’s Diesels and Dinosaurs (1976) focuses exclusively on the American West. The photographs narrate a collision between the prehistoric and the modern, the mythic and the mass-produced: A kitschy dinosaur sculpture looms over a gas station. An ersatz tipi advertises low motel rates. A neon sign glows like a beacon of salvation in the night. For Hostetler, the images reflect Fitch’s background in anthropology. “There’s a sense of studying people,” she says. “It makes me think, ‘What is this alien place where they build dinosaur sculptures and put them in the middle of nowhere?’” Seen through this new iconography, the West is a site of continuous activity and a habitat for frontiersmen and freak shows alike.

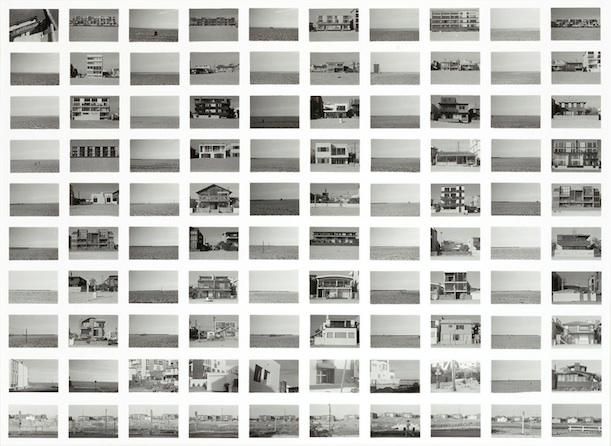

In Robbert Flick’s Sequential Views (1980), the process of making the landscape is as significant as the landscape itself. Flick, influenced by 1970s conceptual art, planned walking routes on a map and set out with rules to govern his photography, clicking the shutter at particular geographic or temporal intervals. To create SV009/80, Marina del Ray, 180 Degree Views, for example, Flick looked one way, took a picture, looked the opposite way, took a picture, moved forward, took a picture and so on. Each piece in Sequential Views contains 100 individual photographs assembled in a 10 by 10 grid using the analog graphic design process called stripping. In Marina del Ray, Flick arranged the photographs into alternating columns of beach and buildings, visualizing the camera’s movement back and forth.

According to Hostetler, this method reveals two principal things about our perception of landscape: 1) that it is often mediated by the automobile and the glimpses we catch in transit; and 2) that it is telegraphic, leaping from one spot to the next. Think about driving: you see a sign in front of you, you get closer to it, you pass it—and your gaze shifts to the next block. The brain fuses these glimpses into a whole greater than the sum of its parts. Flick deconstructs this phenomenon in each photographic array, implicating the viewer in the creation of landscape.

All three artists approached landscape with, if not realism, a new frankness. They acknowledged that tract houses, drive-ins, motels and other roadside attractions were part of the American story—and that the concept of “landscape” is itself fraught with ambiguity. Landscape can mean a sublime and spectacular Bierstadt, but it can also mean nature, the environment generally or something more abstract. Asked to define the term, Hostetler hesitates. “That’s a hard question because I think of as a genre of art,” she says. “But I also think of looking out at our surroundings. I guess when you’re looking at it, it becomes a landscape. The second you take it in as an image, it’s a landscape.”

Elaine Mayes, Steve Fitch and Robbert Flick will discuss their work at a panel discussion on September 12, 2013, at 7:00PM.