It’s Easy to Fall in Love With a Panda. But Do They Love Us Back?

Keepers admire them, but have no illusions. Pandas are solitary creatures

From a distance, a panda seems like it would be easy to love. As the French philosopher Roland Barthes once put it, the adorable is marked by an enchanting formlessness, and few things are as enchantingly formless as a giant panda’s color-blocked visage. Their antics, likewise, are similarly irresistible, recognizably silly in a way no other species can match: What other animal could delight us quite so much by simply tumbling down a snowy hill?

Nicole MacCorkle, a giant panda keeper at the National Zoo, knows that joy well. Having followed the stories about the Zoo’s first pandas Ling-Ling and Hsing-Hsing throughout her childhood, she describes her current work with the species as a dream come true. Ask about her favorite moments with the animals, though, it’s not contact or play that comes to mind. Instead, she thinks back to the public debut of Bao Bao—the Zoo’s three-year-old cub, who will be moving permanently to China on February 21.

“I remember holding her up for the public and looking at the faces in the crowd and seeing how much joy they had,” MacCorkle says. “It’s nice to take a moment and see how they touch humans.”

Those who work with pandas on a daily basis—the people like MacCorkle who sometimes actually touch the animals that emotionally touch humans—tend to have more complicated relationships with their charges, even if they understand our simpler enthusiasm. “Working with pandas, you see all sides of their personalities. You see the grumpy days, or you may see the hints of natural behaviors that are more aggressive, more bear like,” says Stephanie Braccini, curator of mammals at Zoo Atlanta. They are, in other words, a little less adorable up close, their animal eccentricities lending individual texture to these seemingly genial dopes.

That’s not to say that panda keepers can’t take pleasure in the animals in their care; to the contrary, many do. I’ve heard stories of one socially reticent panda keeper who coos improbably at the animals when she’s in their company. But the keepers I’ve spoken to suggest that the pleasure they take from their work is as much about the labor of caring as it is about the species they’re caring for.

“You do create emotional bonds, and you create a tie, and that’s comforting to you because you’re the caretaker for this individual or this species,” Braccini says. “At the root of it, it’s still somewhat selfish. No matter what, you’re the one that’s creating the relationship.”

In this respect, looking after pandas may not be all that different from looking after any other species. Nevertheless, the especially intimate role zookeepers often play in panda conservation efforts can add a special edge to those feelings.

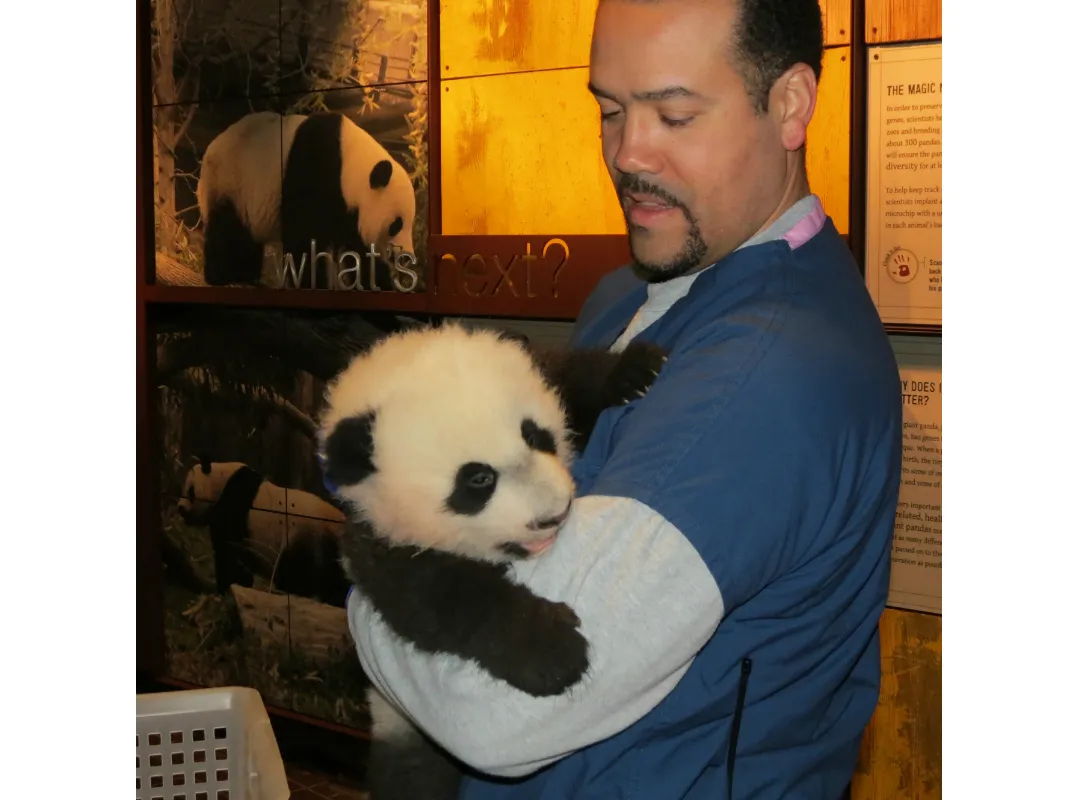

When Marty Dearie, one of the primary panda keepers at the National Zoo, reflects on Bao Bao’s time at the Smithsonian's Zoo—he’s literally been working with her since she was born—he often speaks of aa trip he took to China to learn more about panda-rearing strategies at the Bifengxia Panda Center. Those experiences led the National Zoo to reevaluate certain elements of its approach to panda care, ultimately inspiring it to take what Dearie describes as “a very hands-on” approach. It’s still not quite as forward as that used in China, where, Dearie says, “They actually walk right into the enclosure with the female right after she’s given birth.” Though he and his fellow keepers maintain their distance from the bears—which are, after all, bears—he still had the opportunity to hold Bao Bao when she was just two days old in order to give her a quick physical examination. No keeper at the Zoo had ever touched a panda that early in its life before.

Amazing as it was to watch Bao Bao’s birth, few moments in Dearie’s career have equaled that opportunity to pick her up soon after. “I’ve been a keeper for 15 years and it’s at the top,” he says. “I was literally running down the hall skipping after it happened.”

Given that he’s known Bao Bao her whole life, Dearie unsurprisingly speaks of her in familiar, friendly terms, often referring to her simply as Bao, as befits their years-long relationship. Though he carefully separates professional responsibilities from private feelings, he still acknowledges, “On a personal level, I always say to people that Bao’s one of the most special animals that I’ve ever worked with.” She’s a creature he knows uncommonly well, and it’s that knowledge of her specificity—as well as his own entanglement with her story—that makes her so special to him.

Though all of the giant panda keepers I’ve spoken with share a similar fondness for their charges, none of them had any illusions that their feelings were reciprocated. Solitary in the wild, pandas don’t even have meaningful, lasting relationships with one another. After weaning, “the only time they spend with others of their kind is as babies and then later to mate,” says Rebecca Snyder, curator of conservation and science at Oklahoma City Zoological Park and Botanical Garden.

Dearie’s observations of Bao Bao bear this out: “Within a month of her and [her mother] Mei Xiang separating, they were yelling at each other,” he says. In practice, this inclination to solitude means that pandas don’t have anything that we’d recognize as a “family” dynamic, whether or not they’re in human care.

Despite that, the panda keepers I spoke with told me that pandas can develop significant—if temporary and highly conditional—relationships with humans. But every keeper or expert I spoke with held that those relationships have everything to do with simple sustenance. “They’re adaptable, and they know who brings them the food every day. The fondness is for whoever’s with them,” MacCorkle says. In other words, even if it’s tempting to coo at a panda, the panda is far more interested in who’s bringing dinner.

Within those constraints, however, pandas may still develop different degrees of fondness for different individuals. Comparing them to human toddlers, Braccini suggests that they may keep track of who gives them extra treats or lets them cheat a little in a training exercise. Those connections can pay off: Though keepers at the National Zoo may not enter Bao Bao’s enclosure, Dearie tells me she sometimes plays with the keepers through the mesh—letting them scratch her back, for example. When she does, however, the choice to engage appears to be entirely her own. Indeed, Dearie says the keepers describe her as the “cat of our pandas,” since such interactions always play out on her terms.

Surprisingly, those bonds—such as they are—begin to develop, MacCorkle says, just after the young animals wean—the very point when they’d ordinarily take off on their own. She claims that they’ll engage in contact calling, and sometimes can even be found to sit in strategic spots in the yard that let them watch their keepers. This suggests that humans may help them meet some needs other than the desire for food, though MacCorkle suggests the need may be an effect of their status as zoo animals rather than something species specific. “You have to keep in mind that these are generations of captive-born animals. They’re going to behave differently—somewhat—than their wild counterparts,” she says.

Whatever the reason, the connections that pandas form with humans don’t last long. Driven as they are by their appetites, they’re drawn to those who are close. Despite the years he’s spent with Bao Bao, Dearie doesn’t expect that she’ll miss him—or even remember who he is—after she settles into her new home. “Once she’s in China, within a few days of my leaving, she’s probably going to have forgotten who I am and move on to interacting with her new keepers and building those relationships,” he says. Or, as MacCorkle puts it, summing up the difference, “I don’t think they miss us in the way we miss them.”

That said, the keepers I spoke with almost all echoed the attitudes of their charges, adopting a similarly unsentimental tone when they spoke of sending pandas to China. As Dearie explains, he and his colleagues have been preparing for Bao Bao’s departure from the moment she was born—as would the keepers of any panda born in the United States. In their professional capacity, then, many of them stress the importance of ensuring that their charges have an opportunity to reproduce and raise cubs of their own. But that doesn’t mean it’s easy to watch them go.

“I think it’s hardest saying goodbye to the ones you’ve helped raise,” says Braccini. “We saw them grow up. We watched them be born. But it’s just the beginning of their journey.”

The National Zoo is hosting “Bye Bye, Bao Bao” from February 11 through 20, featuring daily Facebook Live events and other happenings on the Panda Cam.