In this Exhibition You Can Play with the Artworks, Or Even Be the Art

A dizzying array of wildly unorthodox works from video games to computer codes makes up this summer’s blockbuster “Watch This!” show

Once, with paint and stone and canvas, it seemed so easy.

But art changed through time as materials did. And with the explosion of film, video and computers in the last century, artists have had new vibrant, electronic methods of expression.

Dozens of examples from the collections of the Smithsonian American Art Museum are flickering, looping, interacting and radiating in the current exhibition “Watch This! Revelations in Media Art.”

How innovative have the artists become in adapting to this new arena? One holds a patent on the software that enabled her work. In Camille Utterback and Romy Achituv's interactive 1999 Text Rain, viewers become part of the artwork. Their images appear on a screen, where viewers can reach out to try and “catch” on their shoulders or in their hands, the falling cascade of letters. More than free verse, the sprinkling of individual letters of a poem—in this case “Talk You,” by Evan Zimroth—gather on the reflected image of a passerby, whether they know it or not. Utterback’s patented video tracking system allows the letters to land on any image that is darker than a certain threshold. Once that threshold is removed, the letters continue their descent down and off the screen. The artists developed it as a freestanding installation at the Interactive Telecommunications Program at New York University, where Utterback was researcher at the time.

Michael Mansfield, the museum’s curator of film and media arts, who organized the exhibition that spans more than 70 years, says that in addition to receiving a patent, Utterback “is revealing something new about our experience with technology.” But, he adds, it’s not only our experience with technology, but something far beyond that that is perhaps more revealing.”

“Watch This!” freely mixes works from different eras in order to have them comment on one another, he says. “One of the things I was very careful not to do in this exhibition was to create a sequential chronology of innovation and invention.”

So older items on projectors fraternize with the most modern items on computer screens. And in the case of Ed Fries’ Halo 2600, he’s reimagining the modern hit “Halo” video game for ancient Atari systems.

“He’s looking at the gaming platforms that came well before him and seeing the limitations that those inventions presented as an inspiration for creative problem solving in order to make a video game,” Mansfield says of Fries, the former vice president of game publishing at Microsoft, who led the team that created the first version of the Xbox game console.

And to do that, he says, “he has to unearth a whole programming archeology.”

The Fries work is also interactive: viewers can play it—just as they can make a virtual wind blow petals in Flower, a surreal video game by designer Jenova Chen and Kellee Santiago. Viewers can take the controls and blow the petal of a flower across a verdant landscape, making strands of grass wave and other flowers bloom for nothing more than pure pleasure.

Both are among the first video games acquired by a United States art museum and were featured in the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s groundbreaking exhibition, “The Art of the Video Game,” in 2012.

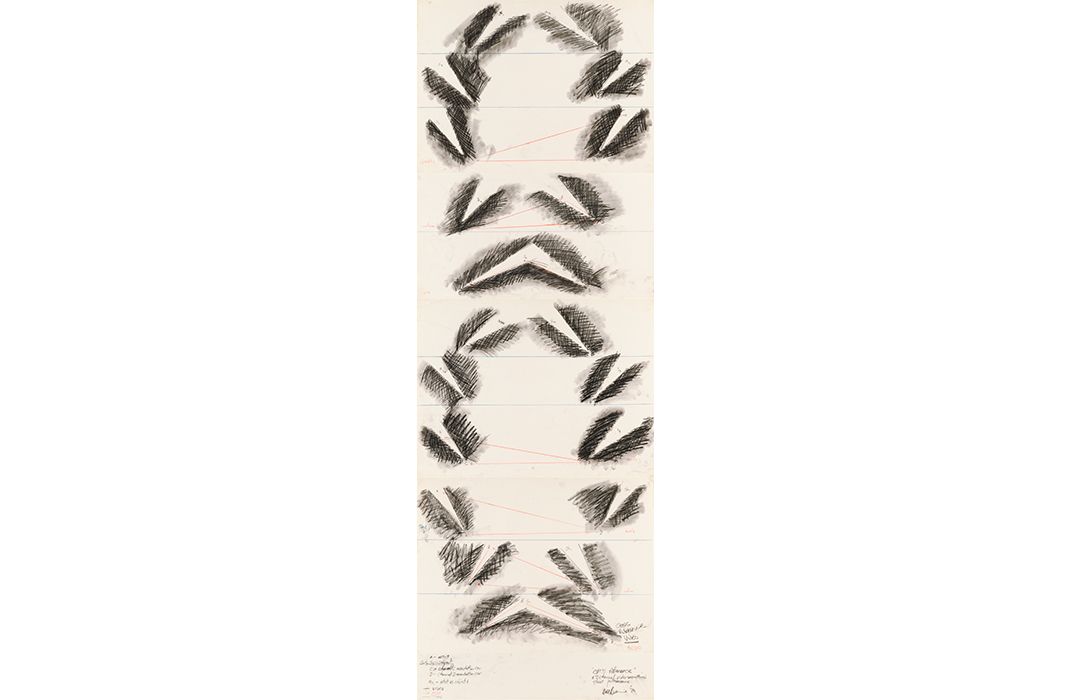

Of the 44 pieces in the show, 30 are on display for the first time, including Hans Breder’s 1964 op art sculpture Two Cubes on a Striped Surface that accompanies his stop-motion animation Quanta.

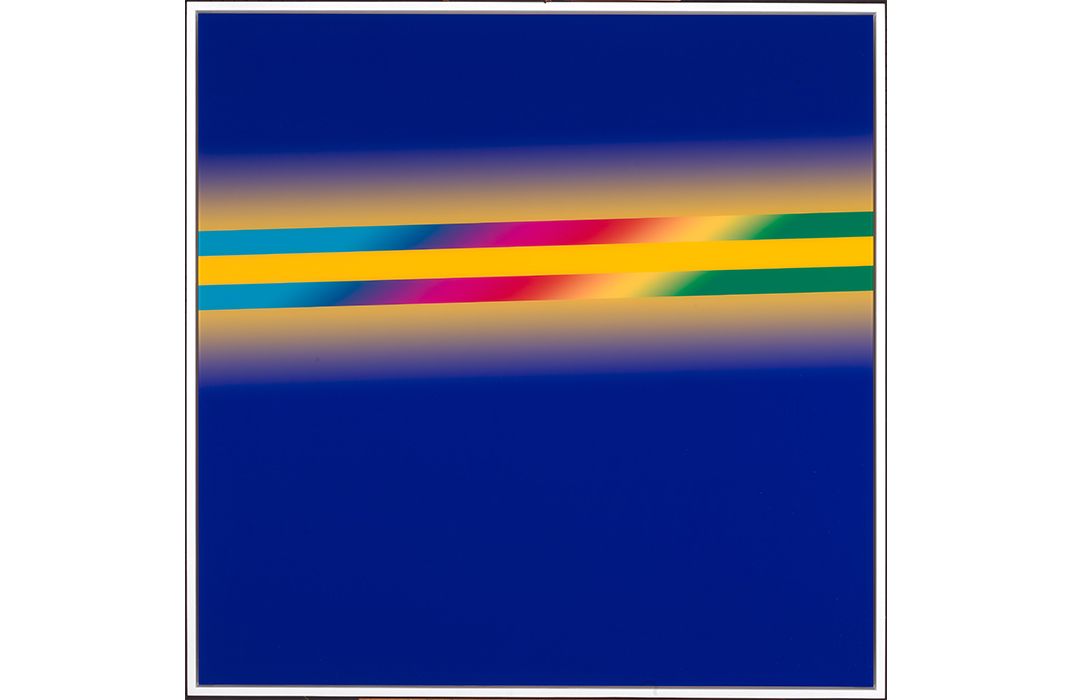

Some of the technical innovations in “Watch This!” are free to share, such as the computer code that provides the title of Cory Arcangel’s work: Photoshop CS: 50 by 50 inches, 300 DPI, RGB, square pixels, default gradient “Blue, Yellow, Blue”, mousedown y=2000 x=1500, mouseup y=9350 x=1650; tool “Wand”, select y=5000, x=2000, tolerance=32, contiguous= off; default gradient “Spectrum”, mousedown y=8050 x=8700, mouseup y=3600 x=5050

(Using those step by step instructions on a computer’s Photoshop software program will give you an image just like Archangel’s parallel lined abstract piece in the show, derived from his series of Photoshop Gradient Demonstrations).

“Watch This” features more than a couple of pieces by the father of video art, Nam June Paik, including the stark lines of his TV Clock—a forgotten work that was rediscoverd in the artist's archives. The piece turns 11 Philco television sets into a clock or a sundial, with each screen portraying a line mimicking the angle of hands sweeping the dial.

In 2009, the museum became the home for the archives of the prolific artist, who died in 2006. Two large Paik works are on permanent display on the same floor—the neon lined Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii and the vibrant Megatron/Matrix that pulsates from its array of 215 TV monitors right at the entrance of the temporary “Watch This!”

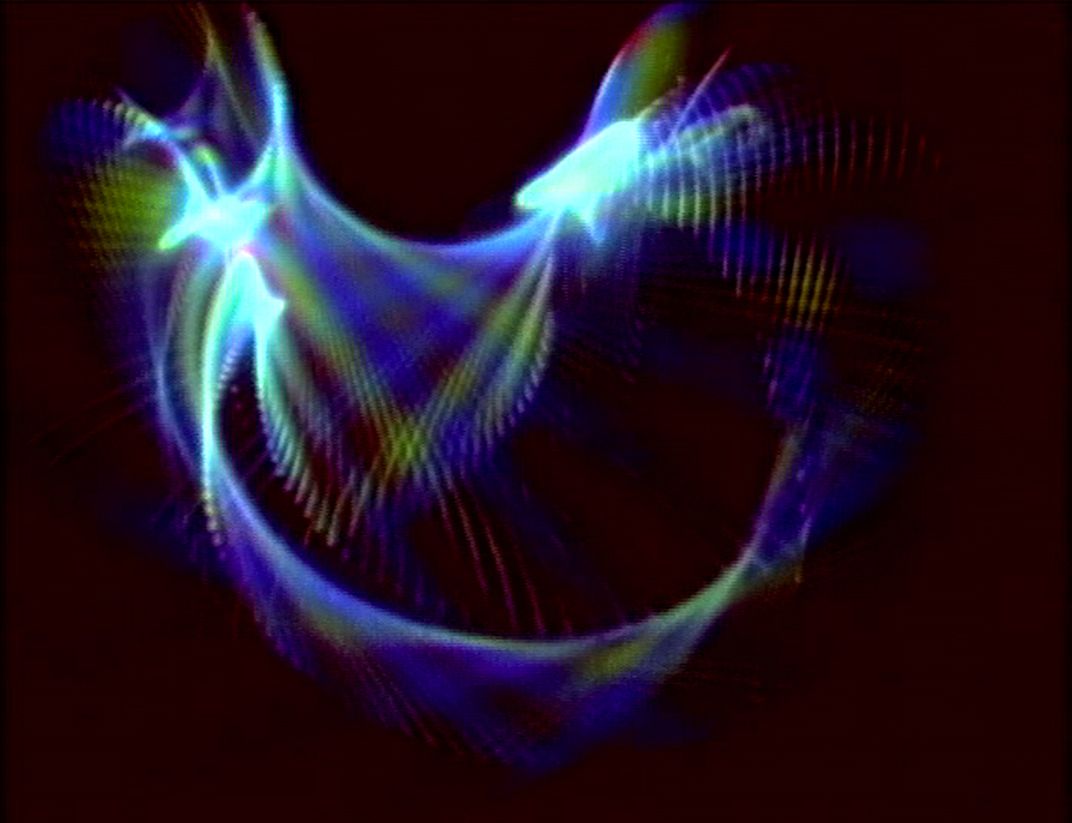

While the newest piece is Archangel’s chromogenic print with the incomprehensible computer code title; the oldest is Dwinell Grant’s Contrathemix, a recently restored 1941 animation he made from a stack of abstract drawings that bring the forms to life. It plays back to back to Raphael Montauez Ortiz’ 1957 Golf, a found film of duffers that has been hand perforated with a hole puncher, creating an overall commentary on white circles, big and small. Another abstracted work is Tekeshi Murata’s 2005 video Monster Movie, full of the kind of digital cubism you might see if your cable is on the blink. A Smithsonian press release calls it “data-moshing.”

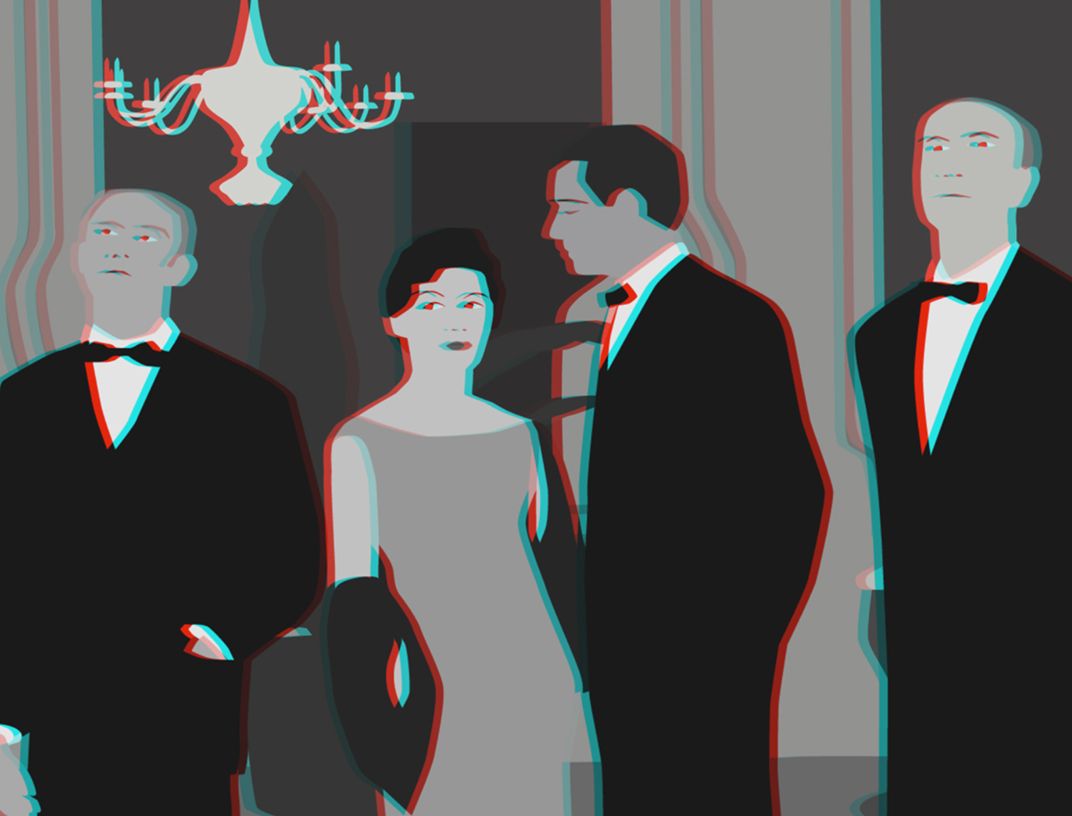

The image used to promote the exhibition is a frame from Kota Ezawa’s LYAM 3D, a digital animation clip from 2008 that takes scenes from Alain Resnais’ 1961 classic Last Year in Marienbad, flattens them into graphic images and presents it in 3D (glasses provided).

Another cinematic experience is provided by Eve Sussman’s whiteonwhite: algorithmicnoir, an enigmatic film of constantly reshuffled scenes, creating an oddly mixed narrative that never repeats itself (the computer code that drives the shuffling rolls enigmatically on a screen nearby).

A set from Sussman’s film—a detailed replica of Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gargarin’s office, is not only the largest installation in the exhibit, it’s one of the few that doesn’t exist on a screen. (Still there is some insight into the film process—chairs are of different sizes so they will appear similar on film).

Because the rise of media art came at a time of great social change, some of that is reflected in the pieces as well, from the feminist rage boiling in Martha Rosler’s 1975 Semiotics of the Kitchen to the mirrored pop violence mash up of Rico Gatson’s 2001 Gun Play.

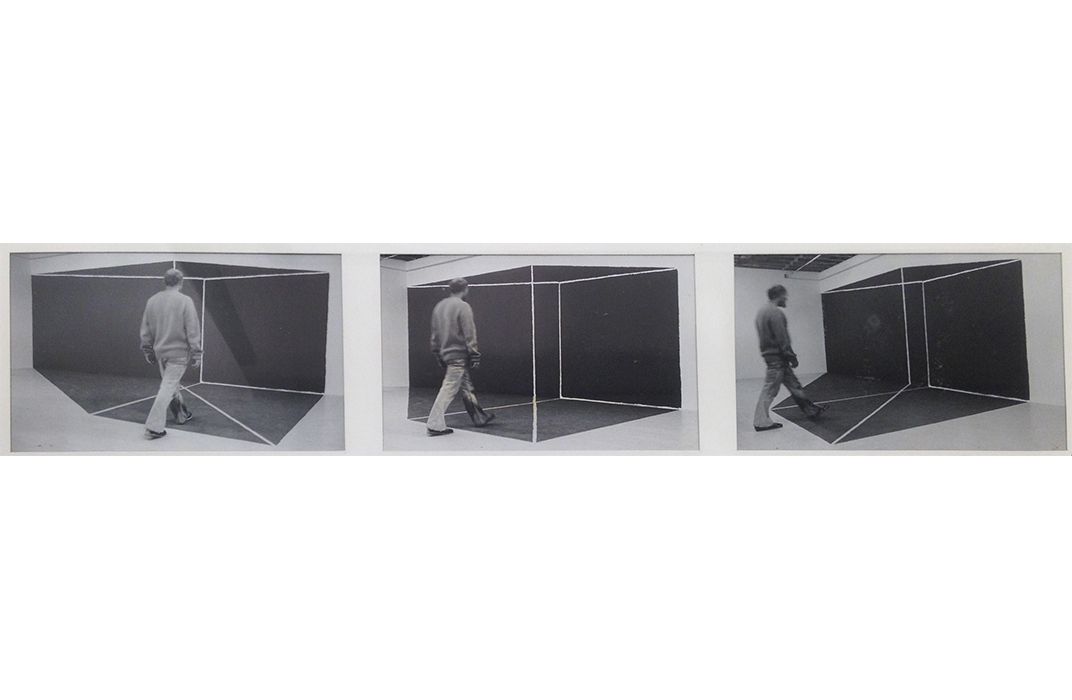

Some have extra resonance in the era of pervasive closed circuit television, such as Bill Beirne’s 1976 two channel Cross Reference in which cameras pointed on city passersby cross. Another closed circuit work is more playful: Bucky Schwartz’ Painted Projection appears to put viewers in a geometric box.

Both are among several works that are accompanied by documentation, storyboards and notes, correspondence and schematics, such as the sight and sound synthesis of Cloud Music, a setup from a late 1970s collaboration by David Behrman, Bob Diamond and Robert Watts that emits electronic tones based on the clouds passing by the nearby window as captured by a stationary video camera.

A couple of the works are culled from another great cache of video art, the 460 artists’ videos from the National Endowment for the Arts’ archives from 1968-1996, when the program was defunded.

From that collection came Christian Marclay’s video “Record Players,” in which he demonstrates other ways that long playing albums could make noise apart from the phonograph (including scratching them with fingernails, rubbing them together and, eventually, breaking them).

“In nearly every one of the works on view,” Mansfield says, “it feels like artists are either touching on inventions that came before them or inventing them outright and working on them in their own studio.” No wonder they seem so at home in the museum housed in Washington’s old Patent Office Building, the first federal exhibition hall in the nation’s capital, once known as “the temple of invention.”

Watch This! Revelations in Media Art continues through Sept. 7, 2015, at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, 8th and F Streets NW, Washington, D.C.

UPDATED May 12: A previous version of this article incorrectly attributed the artwork Painted Projection by Buky Schwartz to Hans Breder. We regret the error.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/69/20/692053ac-d2a3-4564-99c4-585cc18ce3d0/macyo2smallweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/98/d1/98d18f0f-1c64-49fb-80f1-9d1a143f0411/utterbackachituvtextrainweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0e/f1/0ef1b4cb-9d6c-4ecd-b3c4-df663bbddbda/ortizgolf2web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)