The Hyperreal Magnetism of Ron Mueck’s Truly Huge “Big Man”

The sculptor’s showstopper is naked, overweight and grumpy

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bb/95/bb958491-6c28-42b9-97c1-b4109199784e/masterworksinstallation2web.jpg)

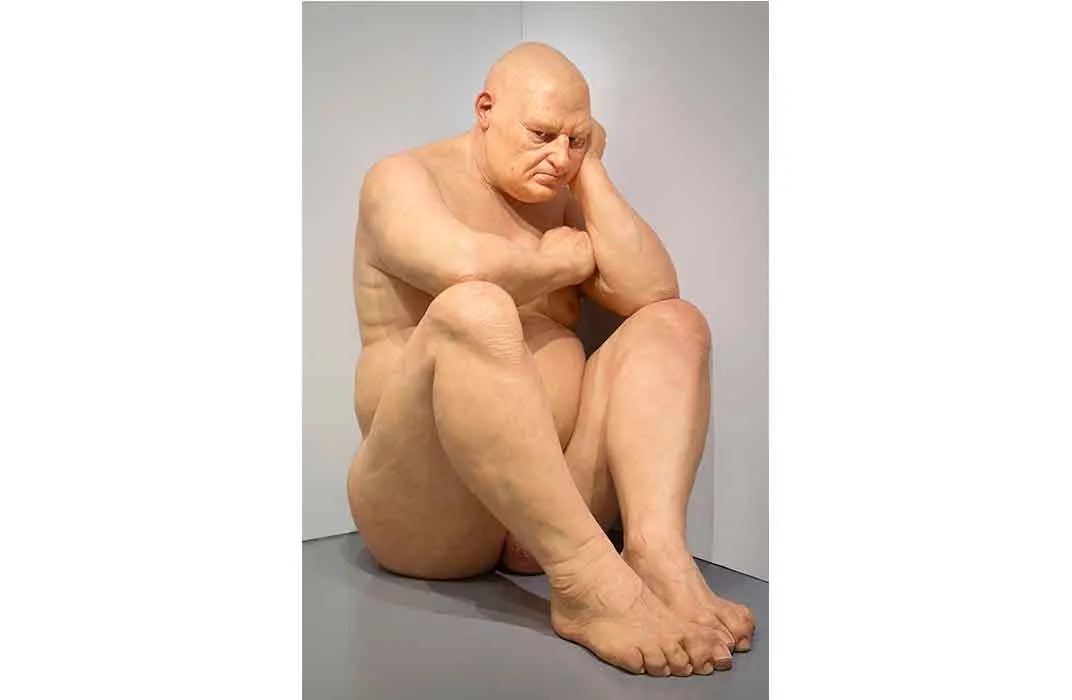

Australian sculptor Ron Mueck thinks big. And his sculpture Big Man, sitting in a corner of the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture in Washington, D.C., is a very big result of that thinking.

Naked, overweight, grumpy, an ungainly Goliath, Untitled (Big Man) is easily the most startling and unexpected piece of art in the entire museum, rising seven feet from the floor even sitting down.

He is a combination of crowd pleaser and crowd pauser, a startling example of Mueck’s hyperrealistic style.

Other sculptors have thought big, too, of course. Anyone who has stood looking up at Michelangelo’s statue of David in Florence, or gone into New York harbor to gawk at the Statue of Liberty, will know that. And the idea of reality has long been seen in classical Greek works, Antonio Canova’s marbles, Auguste Rodin’s bronzes, and George Segal’s ghostly white plaster replicas of ordinary folk.

But Mueck takes size and verisimilitude to another level, giving his pieces hair, eyebrows, beard stubble, even prosthetic eyes. The combination of 3D, photographic realism and unusual scale, usually larger than life but sometimes smaller (he has said that he never makes life-size figures because “it never seemed to be interesting, we meet life-size people every day”) arouse an intense curiosity on museumgoers wherever the pieces are installed.

Big Man, slumped against a wall at the Hirshhorn, has the magnetism of a mythical character. Not heroic, like the David, but awe-inspiring nevertheless.

Stéphane Aquin, the chief curator at the Hirshhorn, calls Big Man “a powerfully affecting work.” Aquin has seen visitors stop in their tracks when they see the oversize sculpture, then walk around studying it. “The way he’s brooding and annoyed, he almost becomes menacing. It’s a strange feeling.”

The fact that Big Man, even sitting down, looms large, adds to the drama, and the hyperrealism can make movement seem possible, even imminent. It’s easy to imagine that at any moment he might stand up, at which point we’d be in Incredible Hulk territory.

“Part of the appeal of the work,” Aquin told me, “is its play on scale and the way we approach it. He’s sitting and we’re standing, so the way we engage with the work is unsettling.”

Ron Mueck (rhymes, more or less, with Buick) was born in Melbourne, Australia, in 1958, and now works in London. He began his career as a model maker and puppeteer on Australian television. He also made props for advertising, though unlike works like Big Man, these were usually only finished on the side facing the cameras. He also created figures for the movie Labyrinth, though he points out that this work “was a tiny cog in a very large machine.” Mueck’s three dimensional, out-of-scale figures are startling in their infinite detailing, and whether larger or smaller than life size, they tend to fascinate global museum patrons.

Curator Aquin says that Mueck is very modest and “quite surprised by his success” since he came out of Australia. For all Mueck’s attention each and every hair and natural-looking skin, he tends to work quite fast in creating his pieces, sometimes within four weeks.

“I usually start with a tiny thumbnail sketch and then do a small maquette in a soft modeling wax to establish a pose and get a feel for the object in three dimensions. If I like the way it’s going, I may go straight to a final clay, or if it’s going to be a large piece, I’ll do a more detailed maquette that nails down the composition, pose and anatomy, which I then ramp up to the final size,” says Mueck.

Whether larger than life size or smaller, the final work, mostly hollow, weighs far less than a normal piece of sculpture might. (Just try moving Michelangelo’s David to sweep underneath.)

Often, Mueck enhances the feeling of hyperreality by adding real clothing, a reference (probably unintended) to the times when Edgar Degas put cloth tutus on bronze figures of young ballerinas. Sometimes, this clothing helps create a narrative, as with the sculpture Youth, a smaller-than-life figure that shows a young black adolescent in blue jeans, lifting a white T-shirt to look in surprise at a stab wound. References to St. Sebastian or Christ may be intended, but the figure seems more immediately alluding to the dangers of life on modern city streets.

About the inspiration for Youth, Mueck says: “I was influenced by news stories, not photographs. There was an insane amount of knife crime among teenage boys occurring in London at the time. Some amazingly similar photos emerged after I had made the sculpture. No model was used for the work. I guess the pose I settled on was quite a natural one in the circumstances I was depicting. And of course the image of Christ showing Doubting Thomas his wound was in the mix.”

Mueck did use a model for Big Man, though he says that is unusual for him. “I was trying to reproduce with the model a sculpture I’d previous made without a model. But the model couldn’t physically assume the pose in the earlier work. He offered to ‘strike’ some other poses, but they all proved ridiculous and unnatural. I asked him to wait for a moment while I thought quickly about what else we could try—I’d only booked him for an hour. I looked over and he was sitting there in the corner in the pose that turned into Big Man. I took some reference Polaroids and he went on his way.”

The sculpture’s facial expression came about accidentally too. “I was struggling to capture his face in a way that satisfied me and in frustration I smacked my hand on the head of the clay figure in front of me. I managed to squash his brows down in a way that made him look kind of angry. It just looked great with the rest of his body language.”

Since, large or small, Mueck’s figures are quite delicate, does he worry about damage in transit? “Yes,” he says, “but they are almost always ingeniously well-packaged by experts whose job it is to protect works of art. Actually, [museumgoers] are a much greater risk. Some cannot resist the urge to confirm with their fingers what their eyes are telling them.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)