How the Unflinching Norman Schwarzkopf Became One Man’s Guiding Light

In a new book, the general who successfully commanded one of the largest military operations in the Middle East is remembered by a man he mentored

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/53/8b/538b1f52-ff6d-49f1-9d0e-30adc1841d9b/schwarzkopfkarsh.jpg)

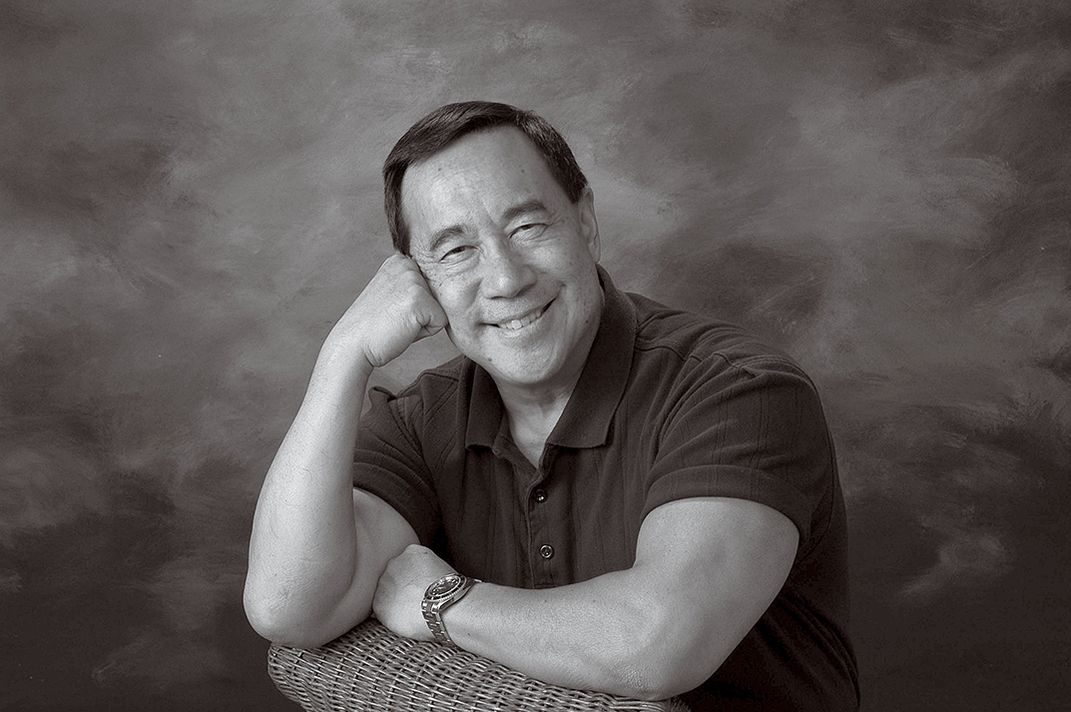

In 1966, an athletic and popular West Point junior-year cadet who preferred playing poker to his engineering studies was about to be kicked out of the prestigious military academy. The line that reeled in the rebellious student would come from none other than H. Norman Schwarzkopf, who in the first Gulf War commanded one of the largest international forces since the Second World War.

Just back from his posting in Vietnam, the then-Major Schwarzkopf took the young Lee under his wing and taught him the discipline and leadership skills that he would later employ as a soldier, a scholar, an educator and an attorney. Lee is also a best-selling author. China Boy, his 1991 fiction (that is also part memoir) about growing up in the 1950s was hailed by the San Francisco Chronicle as a “modern classic.”

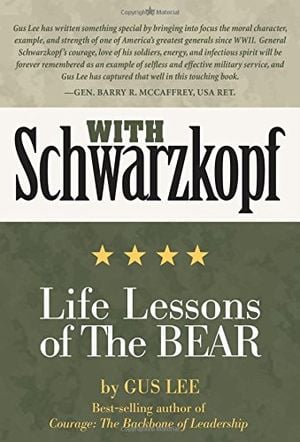

Lee’s 40-year relationship with Schwartzkopf, who he called the “Bear,” is the subject of a new book With Schwarzkopf: Life Lessons of the Bear that tells the untold story of the years when the general counseled his young mentee and his classmates. “Beneath the lessons, the Bear had pounded into our chests the immutable principle that life had always been about leadership, that it would always be about leadership, and as this would require our integrity and courage, we should be about the work of learning how to improve both,” Lee writes. The author spoke with Smithsonian.com about the general, West Point in 1960s and how his own life is grounded by Schwarzkopf’s unwavering principles.

How did you come to write this book?

From the time he was one of my professors at West Point onward, Norm Schwarzkopf’s principles about character guided me through my life. I was at West Point for his funeral in 2013. I was the only cadet he’d maintained contact with across the last half-century, and the only one he’d gone into business with after he retired. I realized I’d never see his great craggy face or hear his memorable voice again. I’d become very busy and hadn’t written a book in a decade, but I felt a stab of duty to write about him and his crystal-clear lessons about how to act and lead with character. John Kotter of Harvard says that we’re 400 percent deficient in leadership right now; I think we need those lessons.

You met Schwarzkopf when he was just a young officer, and you were the only cadet to become his personal, lifelong friend. What was he really like during those early years?

My gosh, what a great guy. He made us smile and laugh and work as never before and also, shake in fear. He told stories that taught us how to live and gave us principles to live by. He was bigger to us than any rock star. He embodied ancient history and a wisdom of the world.

He was scary-brilliant. He was tall and powerfully built and could shrink himself down to a more normally-human size. His graduate degree was in rocket science; we later found out he was in the high genius class. But he could compassionately teach dolts like me.

He quickly and transparently showed his feelings. He was sensitive, sentimental and introspective. He was generous, wanting his cadets to be the best leaders and officers that they could be. He could be so forceful about making moral points that our hair would curl.

Mostly, he was about doing the right thing, whatever the cost. Combined with his outsized personality, there was no way to forget his teachings.

Can you describe what it was like for you to be the rare Asian American cadet at West Point in the 1960s?

I felt very much at first like a stranger in a very strange land. I sort of instantly stood out. But West Point’s exceptionally tough military basic training, called Beast Barracks, melted us all down to a common consistency and then poured us out as young people who could do far more than we ever imagined possible.

I loved the Army as the greatest meritocracy I’d ever know. If you could do the right thing and lead, you were in. It didn’t matter what color you were or if you looked different or spoke with an accent or couldn’t see straight. I was never before more equal as a human being than at West Point and in the Army, societies in which I was always surrounded by people greatly superior to me.

I have no doubt that the Bear picked me out of the 12 cadets in his classroom because I was Asian. He’d just returned from a year of advising the South Vietnamese Airborne in combat, and he missed those men so much he could tear up thinking about them. Being with me eased his guilt of having been ordered out of Asia after his tour of duty to teach at West Point. Not being with his men ate at his very soul.

“The Bear” obviously played a huge role in your life as a mentor; did the lessons he taught you sink right in? Or did they take time to sink in?

I grasped the easy ones, the slow softball pitches that most can hit. But I lacked the backbone—the courage—to work hard enough to make contact with the harder lessons. They looked like 100 mph fastballs and tough curve balls and after I whiffed at them a few times, I said: this is too hard and it’s too touchy-feely. It was a big mistake.

The Bear taught me to respectfully address wrongs in peers and superiors. I wouldn’t do that as a cadet—I kept chickening out. I was a captain in the Army before I found his type of courage to do that, and to willingly accept the heat. Had I practiced it as a cadet, I might’ve helped avoid later problems for the people I didn’t correct.

How tough was “The Bear”?

He was the toughest person I ever knew. He cheerfully took the pains of others on his shoulders. His personal nightmare was to waste lives in war, and he willingly faced his nightmare, again and again, and in buckets in Desert Storm. In personality, he was kinder than gruff, but no one thought of him as having an atom of milquetoast in him.

He was wounded in battle as a young man and had profound back pain from being a Master Paratrooper in two airborne corps and therefore having made way too many jumps. Airborne is really for guys built like me, not him. But his great toughness was in cheerfully taking on the cares of others and being tough enough to accomplish the mission in the highest right way.

You were fortunate to spend the time with Schwarzkopf that you had, share with us your fondest memory of “The Bear”.

West Point profs are experts at asking challenging questions. He looked into my eyes. His pupils bore holes into the back of my head, for his intense gaze was not in search of my brains, which were fleeting, but of my character, which was still being formed. He spoke, his gruff voice as gentle as a thunderstorm.

“Will you do the harder right, regardless of what it costs you?”

The normal response was a crisp, “Yes, sir.”

Will I do the harder right, regardless of what it costs.

He was asking if I would be a person of integrity, of character, or of cowardice and self-interest. I nodded. Yes, I will. It was a vow, equal to the oath we had taken at the river when we began our service to the Nation.

It was the Bear’s classic question, it cut deep within a person, into the true moral self, where the battle is fought between what we are and what we should be.

What are some ways that you apply Schwarzkopf’s principles in your own life to this day?

I’ve been teaching his leadership principles for decades. I see strong traces of his principles in our adult children who are now leaders themselves.

Because of him, I behave more courageously, and became a four-time whistleblower—completely crazy for a recovering coward. Because of him, I’m more generous and caring than is my nature.

He wanted me to discern the highest right, while my natural tendency is to do the most expedient thing in the selfish hope that people might approve of me. He taught me to model the right for the benefit of others, to not be silent when I should speak or passive when I should act, and to believe in the ultimate rightness of all matters. His faith life definitely leaked into my cynical soul, a fact that has blessed my family.

With Schwarzkopf: Life Lessons of The Bear