How One New York City Studio and the Brothers Behind It Helped Popularize the Daguerreotype

Two brothers and their sister built an early photography empire alongside Mathew Brady but watched in crumble in tragedy

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/15/a3/15a3715a-89be-4295-9a30-047b0bd77d63/studio.jpg)

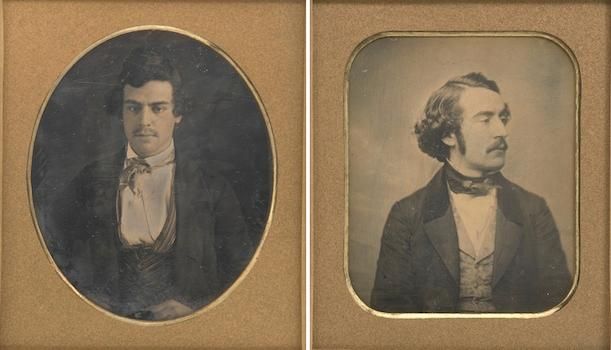

Henry Meade was 20-years old, when he set up his daguerreotype studio in Albany, New York, in 1842. He opened the shop with his brother, Charles, who was just 16. Together the duo, accompanied by their sister Mary Ann, would help introduce the new technology to America, popularizing the portraits sometimes called the “mirror with a memory.” They would eventually move to New York City, first to Brooklyn’s Williamsburg, and then to Manhattan. Their shop at 233 Broadway was prime real estate and just a short walk from Mathew Brady’s studio.

Through a zealous advertising strategy that included visiting the reclusive inventor of the daguerreotype Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre back in France and convincing him to sit for a portrait study—something Daguerre had long refused to do—the brothers, with help from their sister and father, earned a reputation for their skillful work. But their success would be short-lived.

The untimely death of Charles Meade in 1858 at age 31, coupled with the challenges of a rapidly changing technology left Henry in debt and suffering from depression. He took his own life in 1865; and his sister was forced to sell the studio. Their reputation would fade. Some of their portraits would stay in the family but many others were lost. Eventually, descendents of the brothers would donate a small collection of their work to the National Portrait Gallery, which opens its show, “The Meade Brothers: Pioneers in American Photography” Friday, June 14.

“The studios that we tend to know better,” explains curator Ann Shumard, “survived for a longer period of time.” Nonetheless, in the period before Henry’s suicide, the team managed to build a four-story enterprise that not only served as a portrait studio but also as a gallery and an equipment shop.

On their travels to Europe, begun when they were still based in Albany, they learned more about the technology and new trends. The daguerreotype was first invented in France in 1839 but made its American debut just two years later. The technology used silver-coated plates, primed with vapors of iodine, bromine or chlorine that left light-sensitive salts on the plate’s surface. The plate was then placed into the camera, exposed to the light and later developed with fumes of heated mercury. Exposure times required were often long, making the medium best-suited for portraits, precisely the business the Meade brothers intended to make big.

When Charles visited Louis Daguerre in France, Shumard says his boyish persistence convinced the inventor to sit for a series of portraits. He brought these back as a blessing for his business. They printed copies of the rare portraits, created lithographs with his image and invited people to their gallery to see them for themselves. When they donated a memorial stone to the Washington Monument in 1854, it read that it was from “two disciples of Daguerre.”

They created tokens with their company slogan, sold portrait cases emblazoned with the phrase “As taken by Meade & Brother Albany, N.Y.” and even sent images they had taken of Niagara Falls to royalty in Europe, who wrote back complimenting their work.

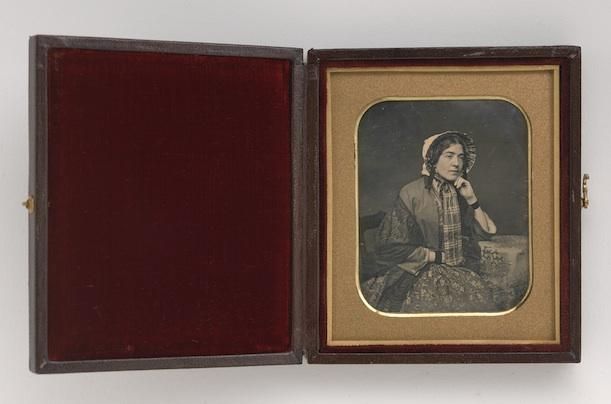

The brothers also had artistic ambitions and staged elaborate scenes of allegorical themes like the “Four Quarters of the World” and the “Seven Ages of Man,” in which models were made to represent the globe’s regions or the journey of aging. In the end, though, the portraits remained more popular.

“The experience of going and having your portrait made was almost like going to a museum,” says Shumard. Before moving to New York City, the brothers were already advertising that their new studio had more than 1,000 daugerreotypes on view. To compete with each other, photographers would spend endless sums turning their studios into luxurious galleries with reception rooms, changing areas and running water. Having put so much money into their Broadway location, the brothers were not prepared for the economic hit that would come with changing technology. As negatives and paper prints suddenly became popular, photographers had a harder time making their work profitable.

Around this time Charles, who seemed to be the driving force behind the studio’s constant innovation, contracted tuberculosis. After his death, his sister Mary Ann, who had always been involved in the business but whose name was left off promotional materials, took over as gallery director in 1862. As for Henry, with his marriage on the rocks and the financial difficulties of the business weighing on him, Henry committed suicide, swallowing vials of poison at the Tammany Hotel.

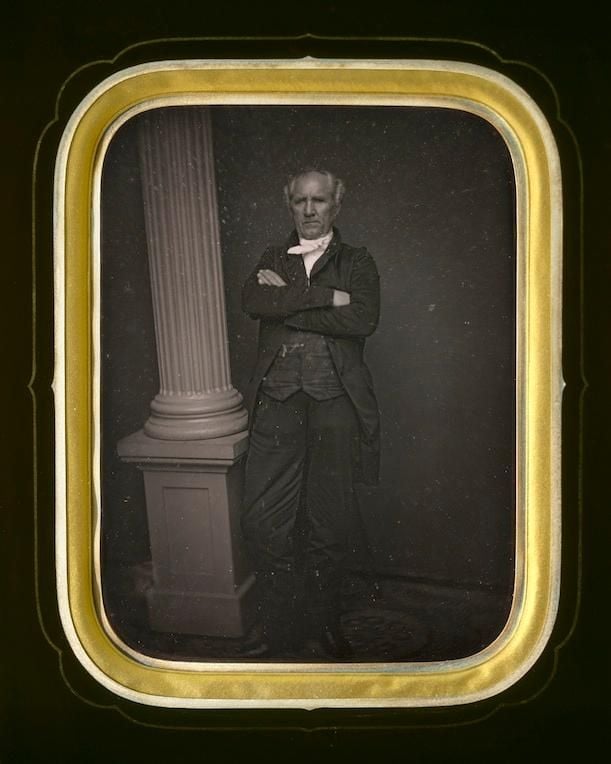

The brothers had captured everyone from statesmen and politicians to actors and popular figures of the day. Though they would move into paper copies, their daguerreotypes left a one-of-a-kind record. “This was actually in the room with Sam Houston” Shumard says pointing to a large-format daguerreotype of the Texas statesman. “This is an artifact of that sitting.”

“The Meade Brothers: Pioneers in American Photography” will be on view at the National Portrait Gallery through June 1, 2014.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)