How the Office of the Vice Presidency Evolved from Nothing to Something

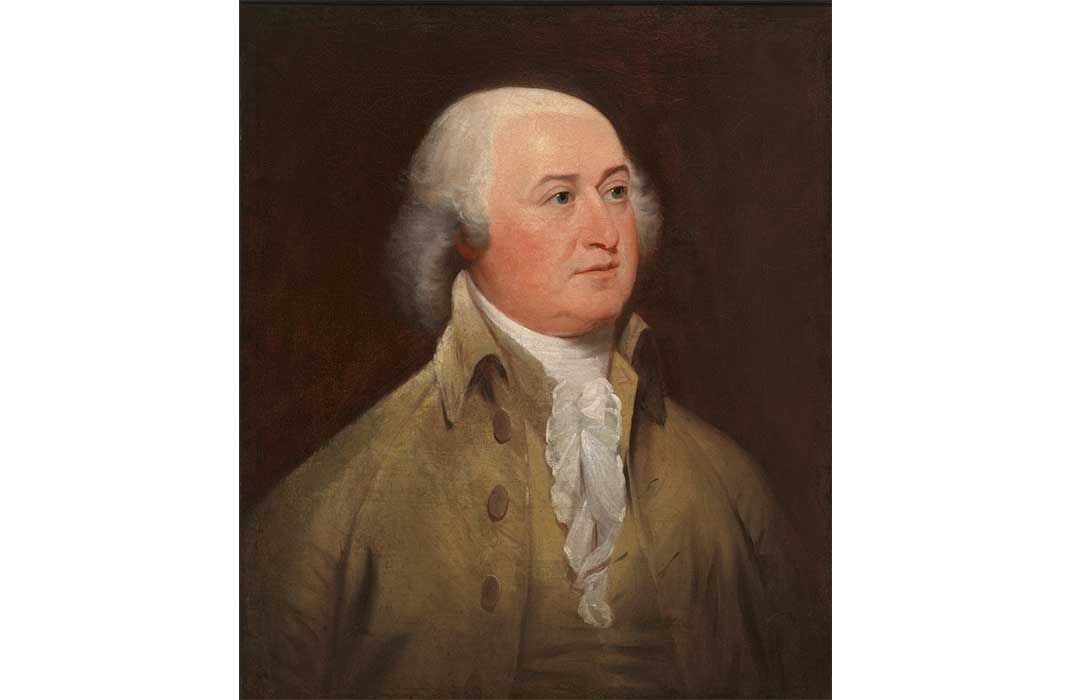

Vice President John Adams once said “In this I am nothing, But I may be everything.” A new book tells how the office has moved from irrelevance to power

:focal(548x285:549x286)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/00/46/00462752-8ba7-4380-83e5-6b39812083ce/npg_2011_55-bush-gore-cheney.jpg)

The office of the vice president has an underwhelming past. The country's founders saw it as a backstop measure. The VP would be a kind of president-in-waiting, should the president die or become disabled. But the founders concluded that the officeholder would be short on duties, or as one constitutional convention delegate noted "without employment." So they devised one extra role, to serve as the president of the Senate with just one task—cast the final tie-breaking vote.

In the early years of the young republic, the vice president was often the subject of lame jokes and ridicule, and with reason, says renowned political journalist Jules Witcover. The position, he writes, held "little significance or utility in governing the nation's affairs."

Witcover’s new encyclopedic volume The American Vice Presidency: From Irrelevance to Power, published by Smithsonian Books, traces the evolution of the office and features 47 biographical essays, one for each American vice president. Though many of them like Aaron Burr, Spiro Agnew, Adlai Stevenson or Nelson Rockefeller, are well-remembered for either notorious or distinguished careers, many others, like William R. King of Alabama and William A. Wheeler of New York, are now largely forgotten.

The author’s interviews with Walter Mondale, Al Gore, Joe Biden and Dick Cheney offer insightful commentary on the modern vice presidency. Says Biden: “The way the world has changed, the breadth and the scope of the responsibility an American president has virtually requires a vice president to handle serious assignments, just because the president’s plate is so very full.”

We asked Witcover to detail some of the backstories of the nation's vice presidents. to explain how the role of the vice president has changed, and to offer some advice for the next president in selecting the 48th.

Why did you want to write this book?

As a longtime reporter on presidents I came to appreciate the importance of presidential succession and the wise selection of running mates. I personally witnessed one assassination of a presidential candidate, Robert Kennedy in 1968 in Los Angeles, the attempted assassination of President Gerald Ford in 1975 in Sacramento, and an assassination hoax against Ronald Reagan three months later in Miami, as well as standing a death watch for George Wallace in 1972 at a hospital in Silver Spring, Maryland. These experiences, and traveling with and reporting on every vice president starting with Richard Nixon brought home the same conviction, along with reflections on some of the least impressive choices. From all this I concluded that the selection of a vice presidential nominee, the first and most important decision a presidential nominee faces, should be examined in terms of the qualifications of the presidential nominee himself.

The office of the vice presidency was an afterthought. Why was it created?

In creating the Electoral College to choose a president, the founding fathers decided each elector should submit two names, with the runner-up becoming vice president. In the period before the creation of parties, no consideration was given to the possibility of the two winners reflecting rival views and policies, as happened in the third election with John Adams, nominally a Federalist, as president and Thomas Jefferson, known as an anti-Federalist, as vice president, serving together. The problem was corrected in the 12th Amendment, providing for separate nomination and election of each office.

Why did vice presidents serve for so many years without much of importance to do?

With only two Constitutional functions, to replace the president in the event of death, disability or resignation and to preside over the Senate, they had no governing duties in the executive branch, and in fact were considered part of the legislative branch for purposes of salary. Presidents were uninclined or unwilling to delegate governing roles to them, and the office was not often sought after. Adams wrote Abigail: “In this I am nothing. But I may be everything.”

When did this situation begin to change? When did presidential nominees choose their running mates?

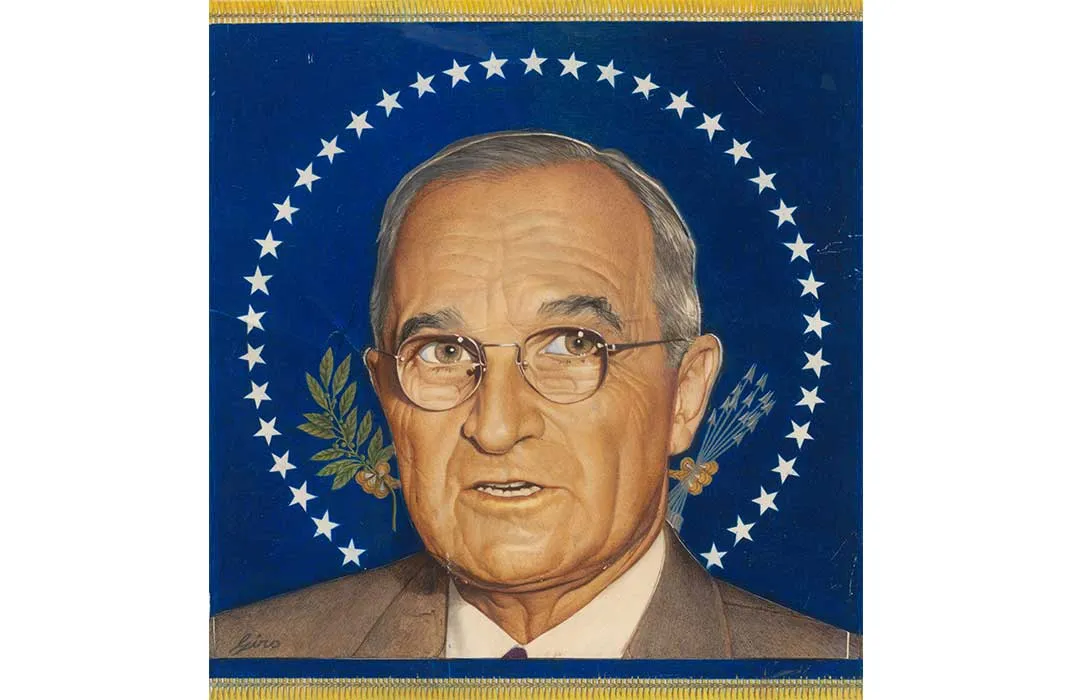

President Jackson in 1832 personally chose his chief political strategist, Martin Van Buren, as his vice president and relied heavily on his counsel. The next time a president chose his running mate was in 1864 when Abraham Lincoln chose to drop Hannibal Hamlin, his first-term vice president, in favor of Andrew Johnson, a War Democrat, to strengthen his chances of reelection. In 1940, FDR demanded under threat of not seeking a third term that Henry Wallace be his running mate. Four years later, he acquiesced in Harry Truman on the advice of political advisers. President Eisenhower was not aware at the time he had a voice in the selection and followed the advice of Thomas E. Dewey and Herbert Brownell.

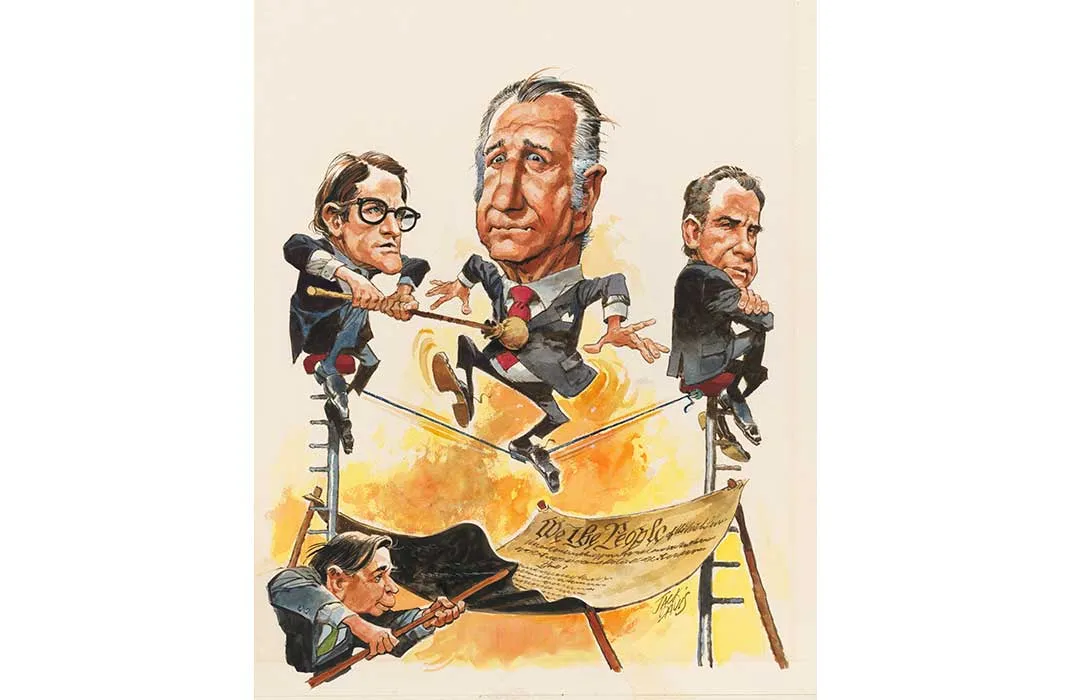

When did vice presidents first take on serious governing responsibilities?

In 1972, Democratic presidential nominee George McGovern's chosen running mate, Sen. Thomas Eagleton of Missouri, was found to have a history of medical illness and was dropped from the ticket. Four years later, Democratic presidential nominee Jimmy Carter, not wanting a repetition, had all prospective vice presidential nominees more thoroughly interrogated and he interviewed six or seven himself, choosing Sen. Walter Mondale of Minnesota for his experience in the Senate and for their compatibility. Mondale had prepared a paper on how he visualized the role of the vice president and was the first to be given an office in West Wing and total access to the Oval Office as a general presidential adviser and partner. The pattern was followed notably by President Bill Clinton with Al Gore, George W. Bush with Dick Cheney, and Barack Obama with Joe Biden.

Who in your opinion have been the best and the worst choices?

Cheney has been the most influential and involved of the vice presidents, but his influence in war-making and expanding presidential powers also were the most controversial. Mondale and Biden particularly have been the most effective in assuming responsibilities assigned by their presidents and maintaining strong personal and constructive relationships with them.

To my mind, the worst and indefensible choice was that by the first President George Bush of Sen. Dan Quayle, who had a mediocre record in the Senate, was given to numerous gaffes as nominee and as vice president, and inspired little confidence as a prospective president. What made his selection particularly irresponsible was the fact that Bush had come close to assuming the presidency himself only ten weeks after becoming vice president, with the assassination attempt on President Reagan. Even in the wake of this choice, in 2008, Republican nominee John McCain chose little-known Gov. Sarah Palin of Alaska, having met her only briefly once before. She was a charismatic candidate but proved to have a serious lack of sophistication concerning major issues of the day. Nixon, unhappy with Agnew, on one occasion considered appointing him to the Supreme Court to get him out of the line of presidential succession! Nixon later regarded him as an "insurance policy" against his own removal in the Watergate scandal, arguing no one would want to elevate Agnew to the presidency. Still later, when Agnew was approaching indictment for taking bribes as governor of Maryland, he was forced to resign to escape jail time in a plea bargain. So Agnew arguably was the worst vice president.

And who in your estimation has been the most consequential vice presidential selection?

In 1864, Lincoln secretly dropped his first vice president, Hannibal Hamlin, a strong foe of slavery, in favor of Andrew Johnson, a defender of the Union in the Civil War to form a unity ticket that would assure his reelection and ability to end the war. As president, Johnson’s reconstruction policies, seen by northern critics as restoring the social order of the old South, complicated the postwar period, which might well have seen more healing policies under Hamlin.

Who was the most selfless, yet also the most mistreated, vice president?

Thomas Marshall under President Woodrow Wilson was kept in the dark about the serious nature of Wilsons’ health after his collapse in 1919 as he sought support for ratification of the Versailles Treaty. He was denied access to Wilson by the president’s wife but resisted advice to seek the presidency on the basis of presidential disability.

Has the vice presidency really been a steppingstone to the presidency?

After the first two vice presidents, Adams and Jefferson, were elected president under the original double-balloting system, Van Buren was the first elected president directly from the office of the vice president, and no other was so elected until George H. W. Bush in 1980. In all, eight of the 47 have ascended by virtue of a presidential death and one, Gerald Ford, in the resignation of Richard Nixon, and none since. The office has on occasion been a steppingstone to a presidential nomination, but none of these vice presidents beyond the senior Bush was ever elected president.

There have been various proposals that vice presidential nominees should be chosen in separate primaries, by party caucus or convention rather than leaving the selection to one person—the presidential nominee. Is this a good idea?

In my mind it’s a very flawed idea. For one thing, the best candidates would seek the presidential nomination. For another, the prospect of a poor match with the presidential nominee would remain present. Finally, recent history has demonstrated that personal and ideological compatibility between president and vice president is critical for a smooth and productive working relationship. The presidential nominee will be best positioned to judge which running mate has the potential to be an effective governing partner. But there is no guarantee that a chosen running mate will work out well. That’s why I believe a presidential nominee’s choice should be yardstick for voters in assessing the qualifications of the presidential nominee himself at the ballot box.

Any advice to our next president on choosing a vice president?

Follow the Mondale model and select a running mate you can be proud of, confident he or she will fill your shoes in a manner that will justify your choice.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Beth_Head_Shot_High_Res-14-v2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2c/5e/2c5e10e1-1d97-4b27-af8c-33b06b4585a7/npg_78_tc374-ford.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/aa/25/aa25de68-a1e6-4257-9e56-9b0ac2c290cd/npg_80_14-det-van-buren.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3c/dd/3cddddf2-1fdc-41ea-a5c7-5b7a43891b19/npg_85_166-johnson.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/de/ca/deca3460-dba6-456b-99ad-068830f80ff5/npg_96_tc33-wallace.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a7/0a/a70abec5-47a2-40d3-8eb1-944fd051ec2a/npg_99_66-jefferson.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a0/f6/a0f6d95c-2fb2-4f3b-8791-ed2e85d73399/npg_2011_45-mondale_ferraro.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/00/46/00462752-8ba7-4380-83e5-6b39812083ce/npg_2011_55-bush-gore-cheney.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3a/77/3a77036f-4fa5-432d-a904-47e66878e1a5/s_npg_79_246_143-hamlin.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/77/96/77969f85-00f5-430c-8a6f-6167cb6a3f55/s_npg_92_195-bush.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Beth_Head_Shot_High_Res-14-v2.png)