How Katharine Hepburn Became a Fashion Icon

Celebrate the Hollywood star with a look at her stellar costumes

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/81/25/812501ae-f9c5-4cde-8c0c-775ea477b970/hepburn2.jpg)

For much of the 20th century, movie stars were the most popular purveyors of public imagery. In the heyday of the Hollywood studio system, each studio created “larger-than-life” stars that projected that studio’s particular brand: Humphrey Bogart did his due diligence as a gangster housed along Warner Bros.’ “Murderers Row” before he finally became a leading man; Greta Garbo was only a Swedish starlet before MGM, home to “more stars than are in heaven,” transformed her into the face of luminous glamour.

Katharine Hepburn, who was born on May 12, 1907 and whom the American Film Institute ranks as the “Number One Female Star of All Time,” was unparalleled in her ability to invent and maintain her own star image. She signed with RKO and went to Hollywood in the early 1930s when the Dream Factory was fixated on platinum blondes draped in sequins and feathers. But Hepburn was cut from a different template, and from the moment she stepped onscreen in the 1932 film A Bill of Divorcement, her unique image made her a “movie star.” Her highly-stylized personality and lanky physique signaled a radical departure from such screen sirens as Jean Harlow and Carole Lombard. Instead, Hepburn conveyed the essence of modernism—a woman who looked life straight in the eye.

Hepburn was part of the post-suffrage generation of women, and her screen persona resonated with that generation’s modern spirit of independence. Despite RKO’s determination to brand her otherwise, Hepburn succeeded in inventing herself. “I was a success because of the times I lived in,” she once said. “My style of personality became the style.”

Costumes played an essential role in fashioning the Hepburn “look,” and it turns out that—like everything else that mattered to her—Hepburn was vigorously involved in all aspects of her clothes. “One does not design for Miss Hepburn,” the Oscar-winning costume designer Edith Head once said. “One designs with her. She’s a real professional, and she has very definite feelings about what things are right for her, whether it has to do with costumes, scripts, or her entire lifestyle.” She wore clothes that allowed her to move freely; offscreen, she favored a sportswear look that reflected her innate athleticism.

When the world’s fashion center, Paris, was engulfed by war in the late 1930s, Hollywood designers filled the gap by projecting an identifiable “American fashion” onto the silver screen. Hollywood’s ascendant fashion significance catapulted Hepburn’s tailored and casual style into prominence as the defining American look. According to leading costume historian Jean L. Druesedow and curator of the traveling exhibition "Katharine Hepburn: Dressed for Stage and Screen," Hepburn captured the moment because “she embodied American style.”

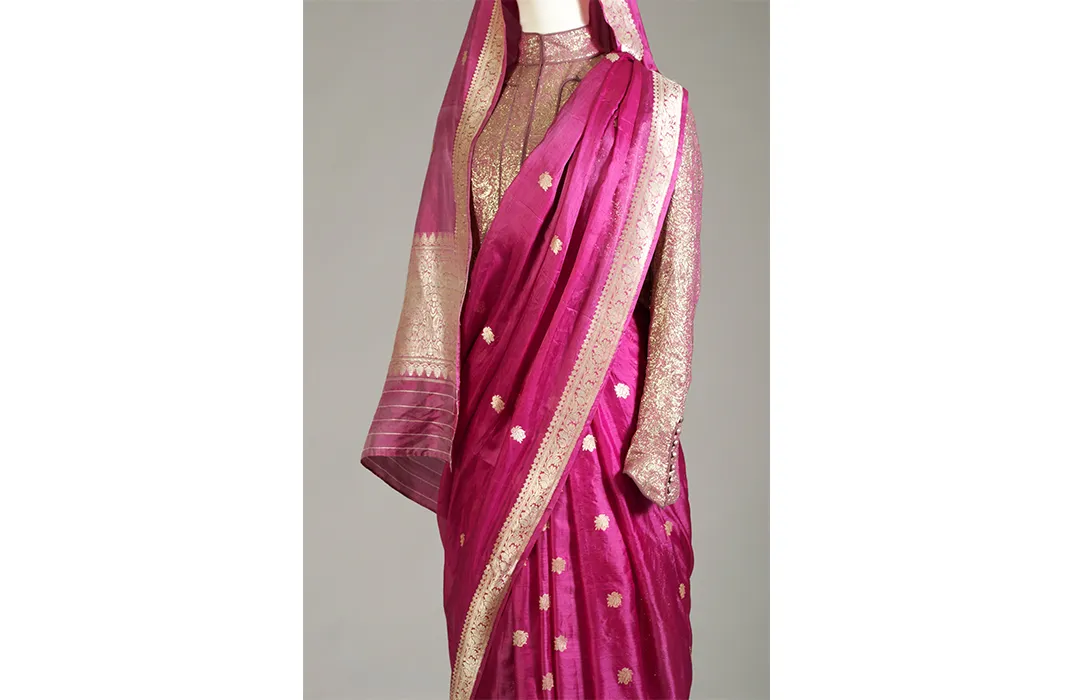

The evolution of Hepburn’s “look” is remarkably revealed through her costume collection. Costumes were always important to Hepburn, and she kept most of them in her New York townhouse. After her death in 2003, the Hepburn Estate donated the collection to the Kent State University Museum, which director Jean Druesedow explains has “one of the most important period costume and fashionable dress collections in the country.”

Since the costumes came to the museum in 2010, Druesedow has discovered that they demonstrate that “Hepburn was very much aware that it was her public image, achieved through her close working relationships with those who designed her costumes …that had kept her fascinating to generations of fans.”

She only worked with the best. On screen, she collaborated with such leading designers as Adrian, Walter Plunkett, Howard Greer and Muriel King; on stage, she especially liked theatrical designer Valentina, who also became one of her go-to private designers. “I do take a tremendous amount of care over my costumes,” Hepburn admitted. “I’ll stand longer over a fitting than anyone. But you can’t judge someone by what he’s wearing. It’s the inner part that counts.”

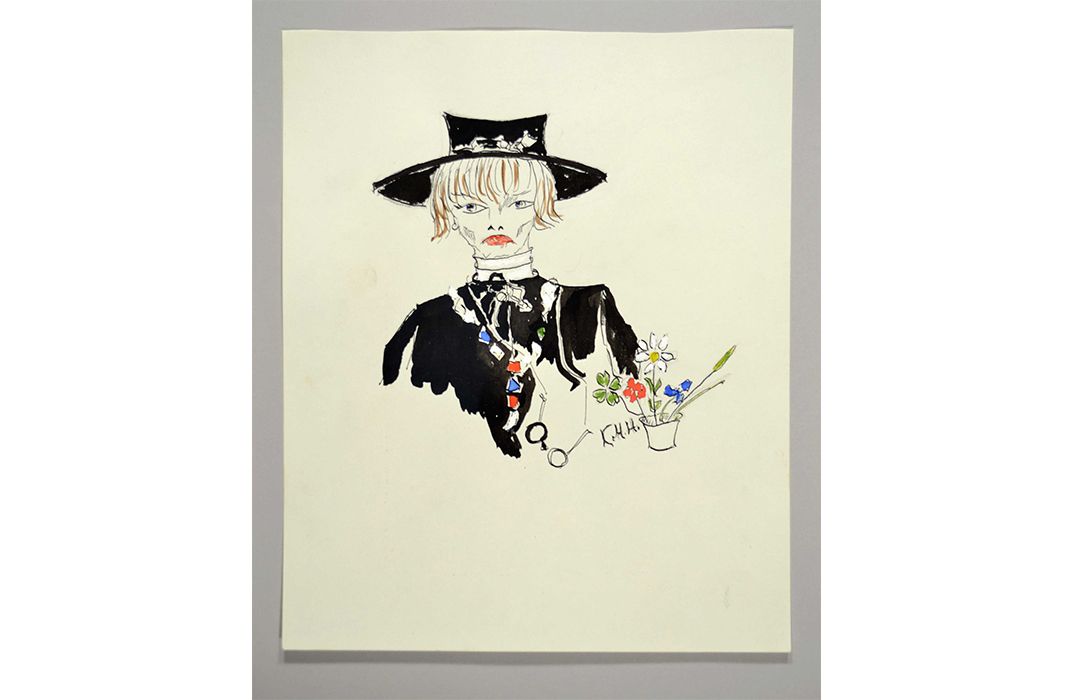

When she was preparing for a role, Hepburn often gave costume designers scrawled notes about her ideas for colors and fabrics. Because costumes helped her portray a role’s character, Hepburn firmly believed that “A star practically always asks for a designer, if she has any sense.”

The Kent State Hepburn collection features about 1,000 stage, screen and television performance costumes as well as some of Hepburn’s offstage clothes, including over 30 custom-made tan slacks. Once the collection was acquired, director Jean Druesedow told me that the great challenge was to identify the performance for which each costume was used. This daunting research was undertaken at the New York Public Library, where Hepburn’s stage papers are archived, and at the Academy of Motion Pictures Library in Beverly Hills, which archives her movie career; so far, nearly 100 costumes have been successfully identified. A selection was shown in a 2012 exhibit at the NYPL, Katharine Hepburn: Dressed for Stage and Screen, and a larger selection in 2015 at Omaha’s Durham Museum; there is also an accompanying catalogue, Katharine Hepburn: Rebel Chic (Skira/Rizzoli, 2012).

Hepburn’s impact on American fashion was officially recognized in 1985 when the Council of Fashion Designers of America presented her with its Lifetime Achievement Award. Her “look” was an essential expression of who she was and clearly contributed to her popularity at the box office for over six decades. Character, costumes, everyday clothes—all merged into an indomitable image that proclaimed “Katharine Hepburn.” As she told Dick Cavett in a 1973 PBS interview, “I am absolutely fascinating!”

Katharine Hepburn: Rebel Chic

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4f/b3/4fb3ca76-0b41-4402-8985-6784be996865/20101218a-floveamongtheruinsweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3f/db/3fdbebc7-0238-41d0-a956-8faab5fa07fd/20101212abadelicatebalanceleopardweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/74/22/7422bc15-e097-403a-b451-02f0fe98422f/2010129lavenderldjinweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d2/f5/d2f5e5fa-113b-4ef7-b328-c9a11b8dae55/2010122abstagedoorweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/97/6a/976a5b5e-db52-4a69-a0ba-a514e813c524/2010121athelittleministerweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/75/e7/75e7d432-fc1c-4485-a7bf-52796b8e9d3a/20101253weddingdressthelakeweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)