How the Inca Empire Engineered a Road Across Some of the World’s Most Extreme Terrain

For a new exhibition, a Smithsonian curator conducted oral histories with contemporary indigenous cultures to recover lost Inca traditions

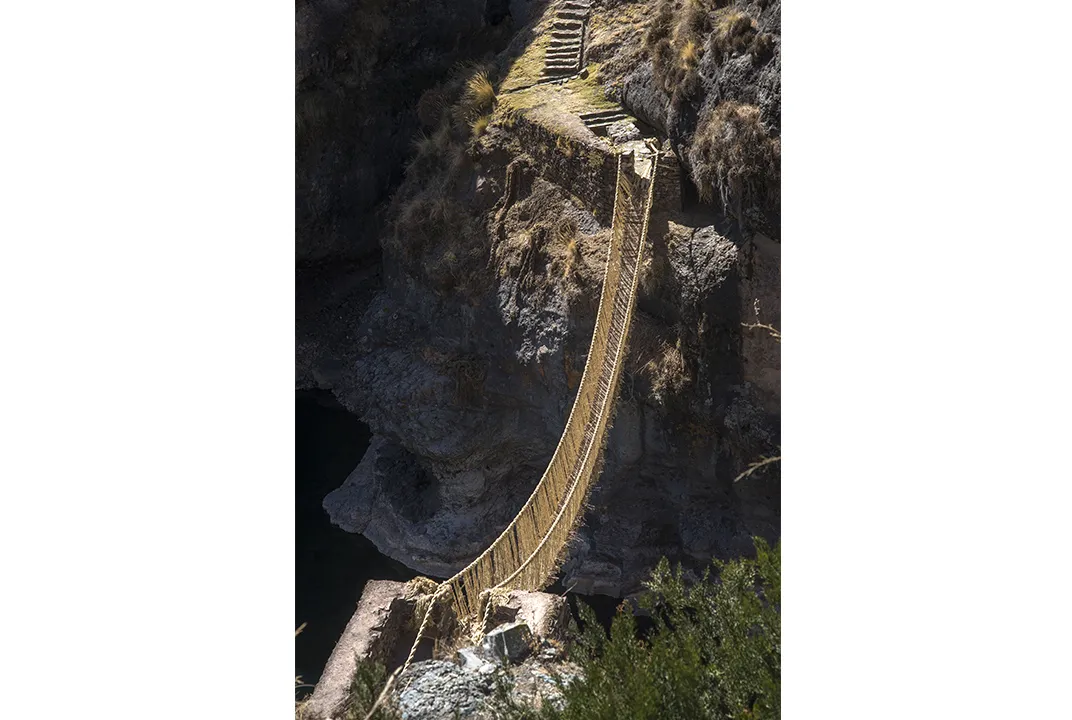

Every June, after the rainy season ends in the grassy highlands of southern Peru, the residents of four villages near Huinchiri, at more than 12,000 feet in altitude, come together for a three-day festival. Men, women and children have already spent days in busy preparation: They’ve gathered bushels of long grasses, which they’ve then soaked, pounded, and dried in the sun. These tough fibers have been twisted and braided into narrow cords, which in turn have been woven together to form six heavy cables, each the circumference of a man’s thigh and more than 100 feet long.

Dozens of men heave the long cables over their shoulders and carry them single file to the edge of a deep, rocky canyon. About a hundred feet below flows the Apurímac River. Village elders murmur blessings to Mother Earth and Mother Water, then make ritual offerings by burning coca leaves and sacrificing guinea pigs and sheep.

Shortly after, the villagers set to work linking one side of the canyon to the other. Relying on a bridge they built the same way a year earlier—now sagging from use—they stretch out four new cables, lashing each one to rocks on either side, to form the base of the new 100-foot long bridge. After testing them for strength and tautness, they fasten the remaining two cables above the others to serve as handrails. Villagers lay down sticks and woven grass mats to stabilize, pave and cushion the structure. Webs of dried fiber are quickly woven, joining the handrails to the base. The old bridge is cut; it falls gently into the water.

At the end of the third day, the new hanging bridge is complete. The leaders of each of the four communities, two from either side of the canyon, walk toward one another and meet in the middle. “Tukuushis!” they exclaim. “We’ve finished!”

And so it has gone for centuries. The indigenous Quechua communities, descendants of the ancient Inca, have been building and rebuilding this twisted-rope bridge, or Q’eswachaka, in the same way for more than 500 years. It’s a legacy and living link to an ancient past—a bridge not only capable of bearing some 5,000 pounds but also empowered by profound spiritual strength.

To the Quechua, the bridge is linked to earth and water, both of which are connected to the heavens. Water comes from the sky; the earth distributes it. In their incantations, the elders ask the earth to support the bridge and the water to accept its presence. The rope itself is endowed with powerful symbolism: Legend has it that in ancient times the supreme Inca ruler sent out ropes from his capital in Cusco, and they united all under a peaceful and prosperous reign.

The bridge, says Ramiro Matos, physically and spiritually “embraces one side and the other side.” A Peruvian of Quechua descent, Matos is an expert on the famed Inca Road, of which this Q’eswachaka makes up just one tiny part. He’s been studying it since the 1980s and has published several books on the Inca.

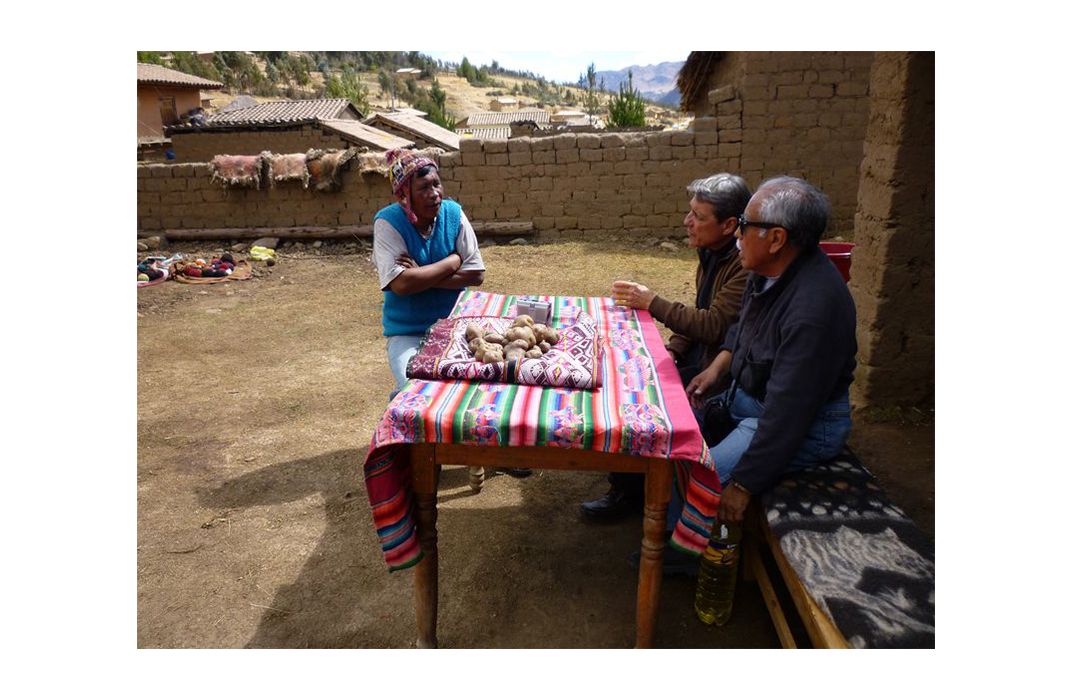

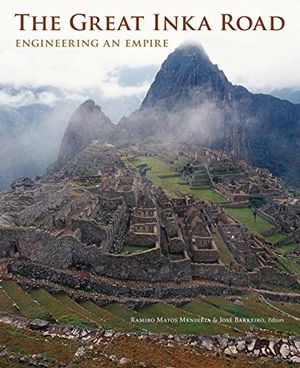

For the past seven years, Matos and his colleagues have traveled throughout the six South American countries where the road runs, compiling an unprecedented ethnography and oral history. Their detailed interviews with more than 50 indigenous people form the core of a major new exhibition, “The Great Inka Road: Engineering an Empire,” at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian.

“This show is different from a strict archaeological exhibition,” Matos says. “It’s all about using a contemporary, living culture to understand the past.” Featured front and center, the people of the Inca Road serve as mediators of their own identity. And their living culture makes it clear that “the Inca Road is a living road,” Matos says. “It has energy, a spirit and a people.”

Matos is the ideal guide to steer such a complex project. For the past 50 years, he has moved gracefully between worlds—past and present, universities and villages, museums and archaeological sites, South and North America, and English and non-English speakers. “I can connect the contemporary, present Quechua people with their past,” he says.

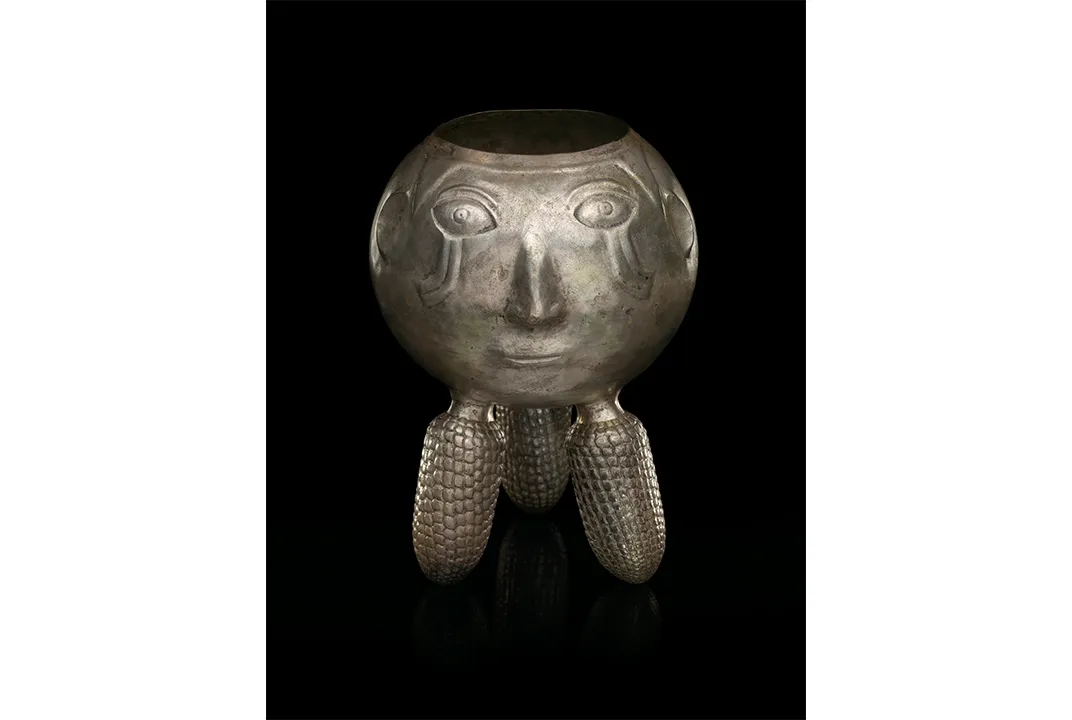

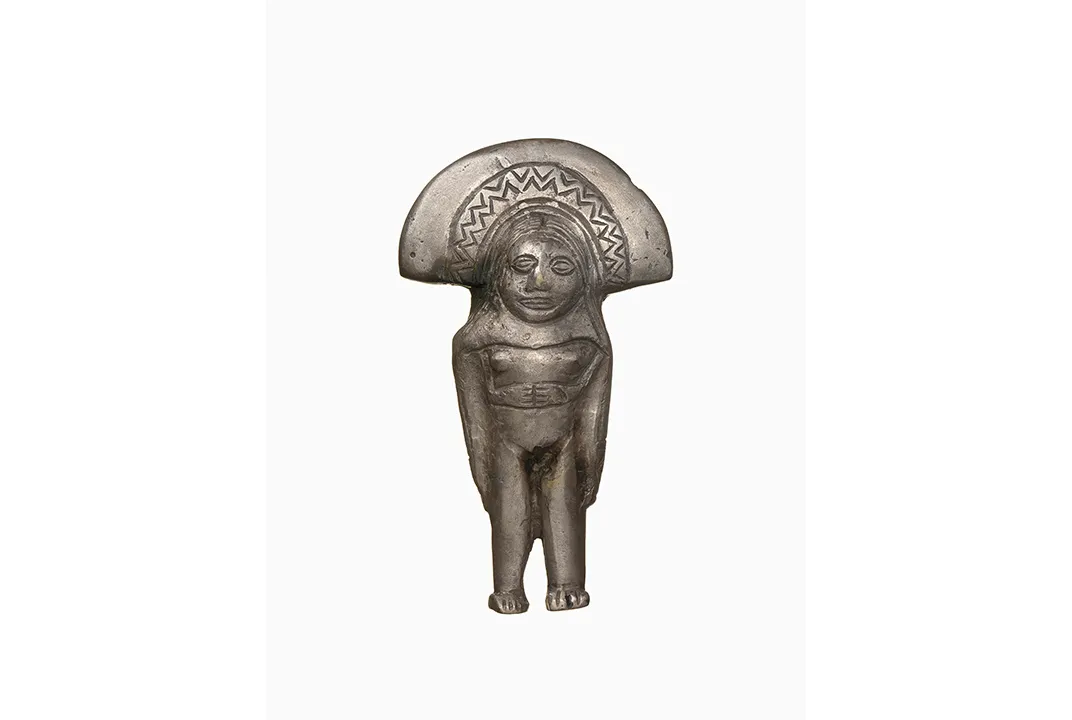

Numerous museum exhibitions have highlighted Inca wonders, but none to date have focused so ambitiously on the road itself, perhaps because of the political, logistical and conceptual complexities. “Inca gold is easy to describe and display,” Matos explains. Such dazzling objects scarcely need an introduction. “But this is a road,” he continues. “The road is the protagonist, the actor. How do we show that?”

The sacred importance of this thoroughfare makes the task daunting. When, more than a hundred years ago, the American explorer Hiram Bingham III came across part of the Inca Road leading to the fabled 15th-century site of Machu Picchu, he saw only the remains of an overgrown physical highway, a rudimentary means of transit. Certainly most roads, whether ancient or modern, exist for the prosaic purpose of aiding commerce, conducting wars, or enabling people to travel to work. We might get our kicks on Route 66 or gasp while rounding the curves on Italy’s Amalfi Coast—but for the most part, when we hit the road, we’re not deriving spiritual strength from the highway itself. We’re just aiming to get somewhere efficiently.

Not so the Inca Road. “This roadway has a spirit,” Matos says, “while other roads are empty.” Bolivian Walter Alvarez, a descendant of the Inca, told Matos that the road is alive. “It protects us,” he said. “Passing along the way of our ancestors, we are protected by the Pachamama [Mother Earth]. The Pachamama is life energy, and wisdom.” To this day, Alvarez said, traditional healers make a point of traveling the road on foot. To ride in a vehicle would be inconceivable: The road itself is the source from which the healers absorb their special energy.

“Walking the Inca Trail, we are never tired,” Quechua leader Pedro Sulca explained to Matos in 2009. “The llamas and donkeys that walk the Inca Trail never get tired … because the old path has the blessings of the Inca.”

It has other powers too: “The Inca Trail shortens distances,” said Porfirio Ninahuaman, a Quechua from near the Andean city of Cerro de Pasco in Peru. “The modern road makes them farther.” Matos knows of Bolivian healers who hike the road from Bolivia to Peru’s central highlands, a distance of some 500 miles, in less than two weeks.

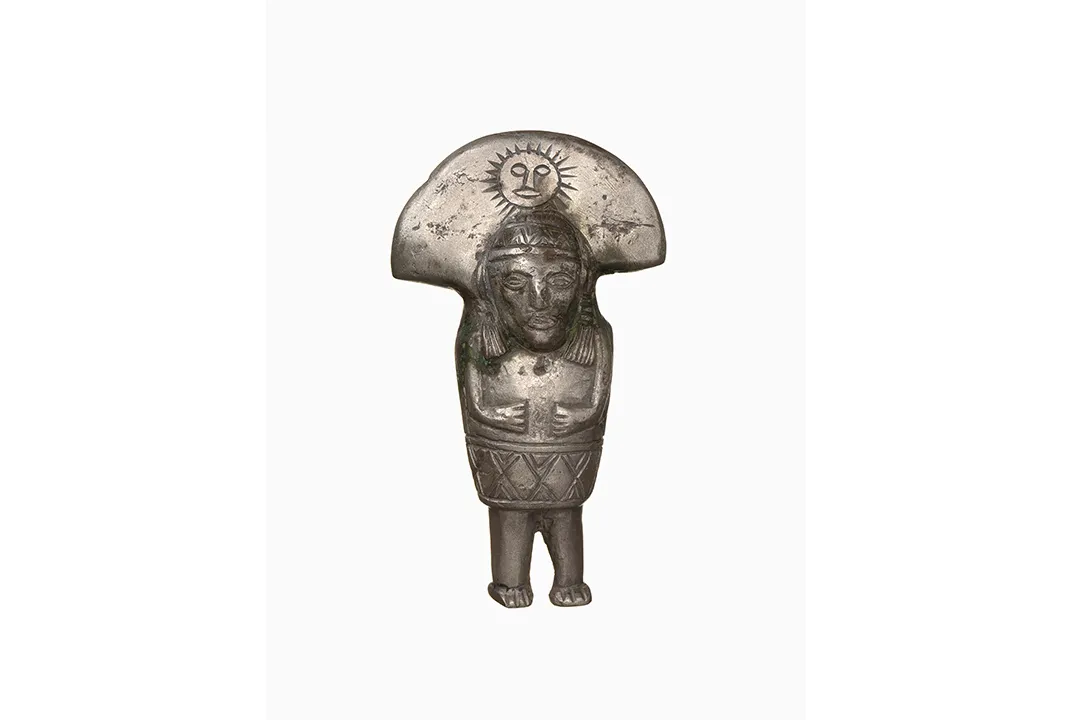

“They say our Inka [the Inca king] had the power of the sun, who commanded on earth and all obeyed—people, animals, even rocks and stones,” said Nazario Turpo, an indigenous Quechua living near Cusco. “One day, the Inka, with his golden sling, ordered rocks and pebbles to leave his place, to move in an orderly manner, form walls, and open the great road for the Inca Empire… So was created the Capac Ñan.”

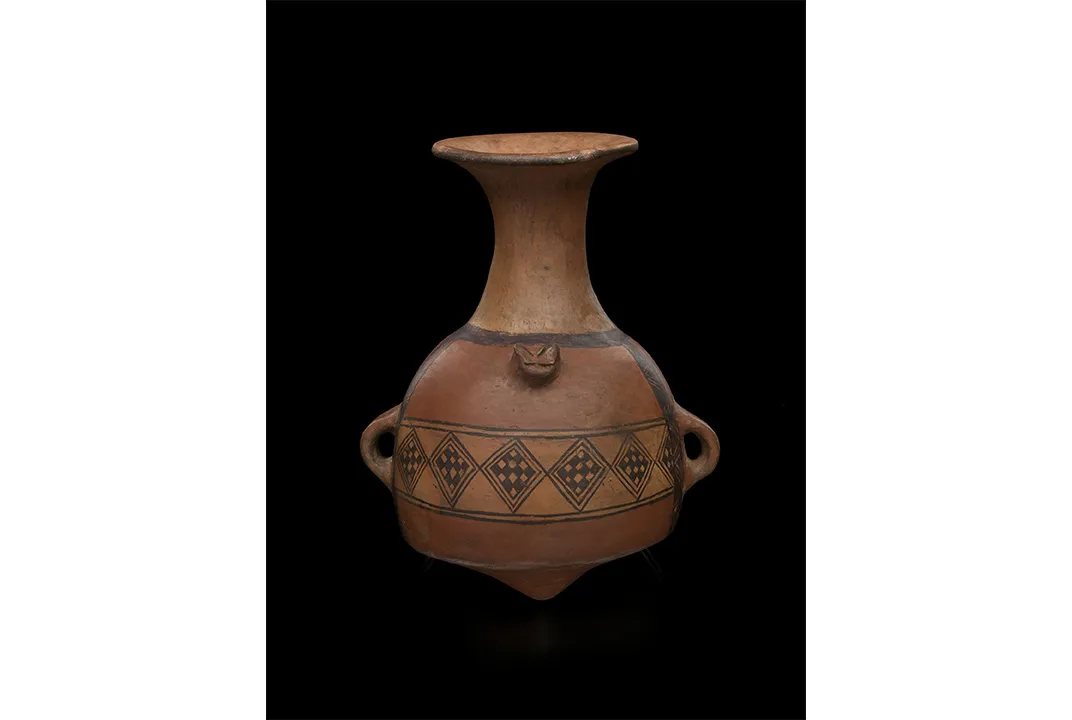

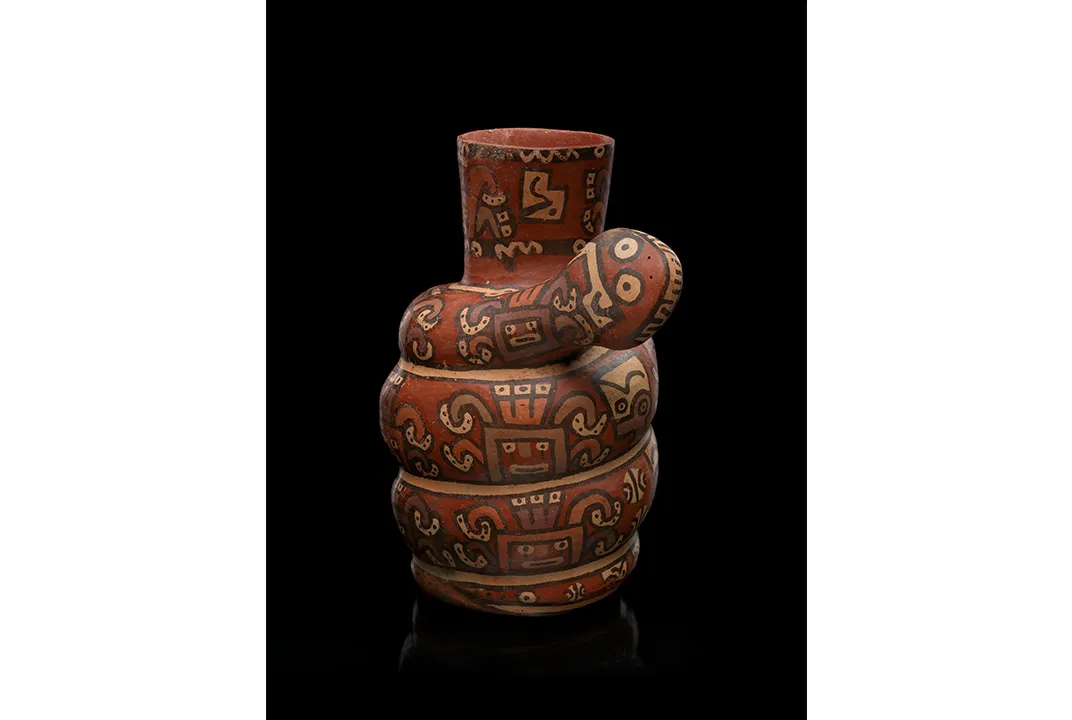

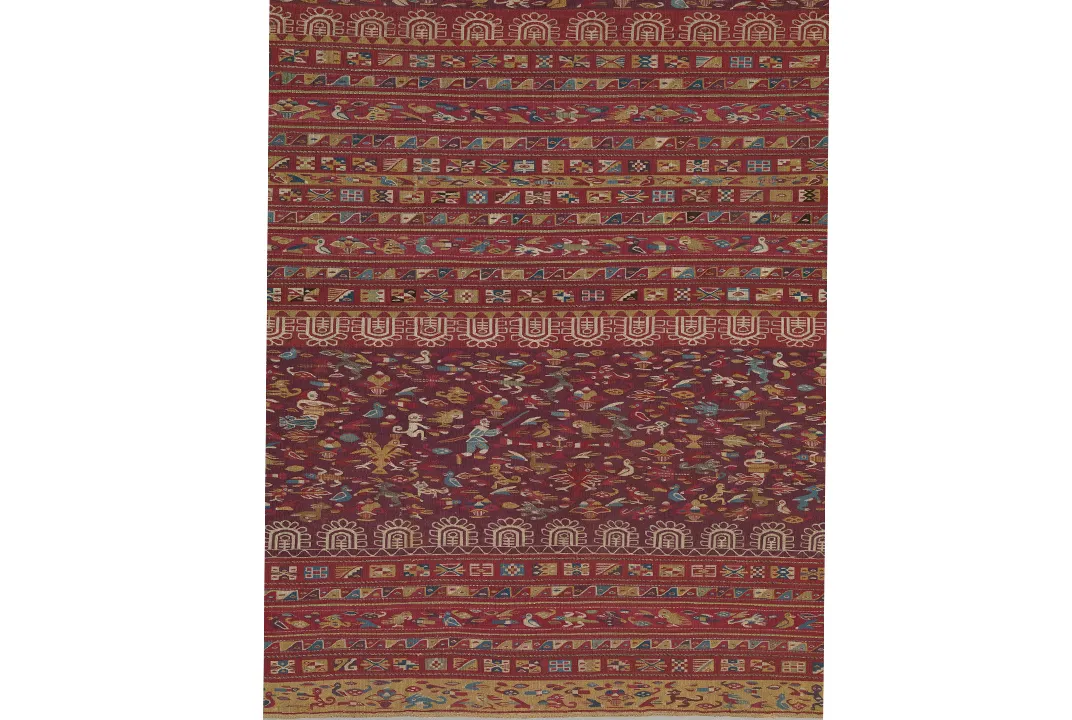

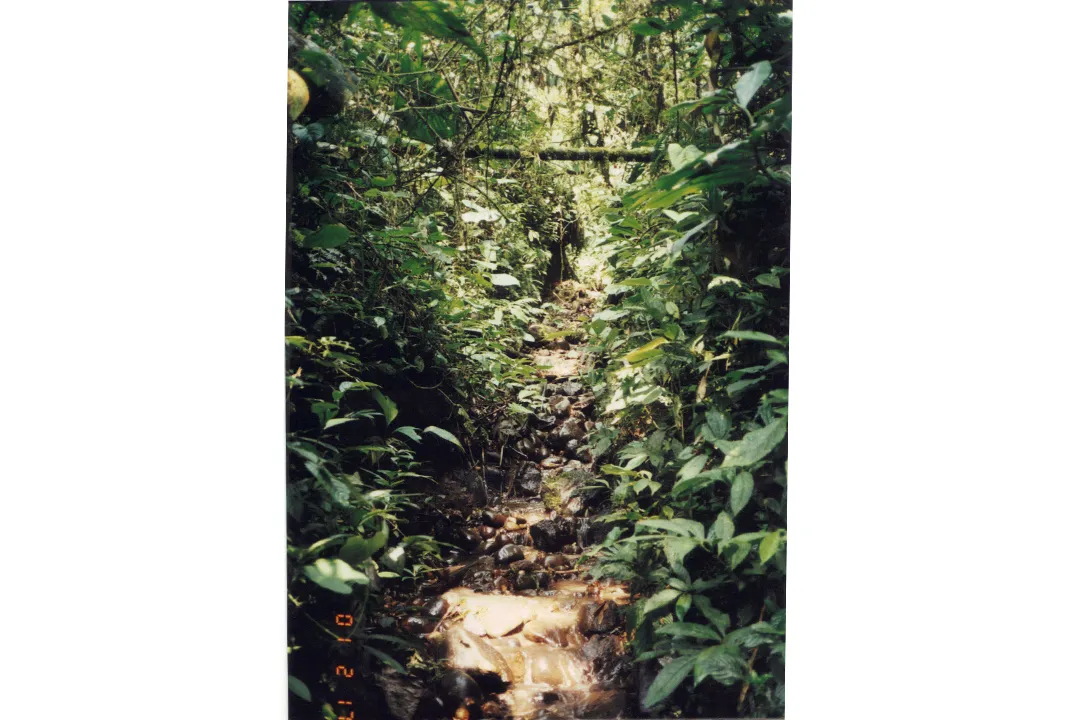

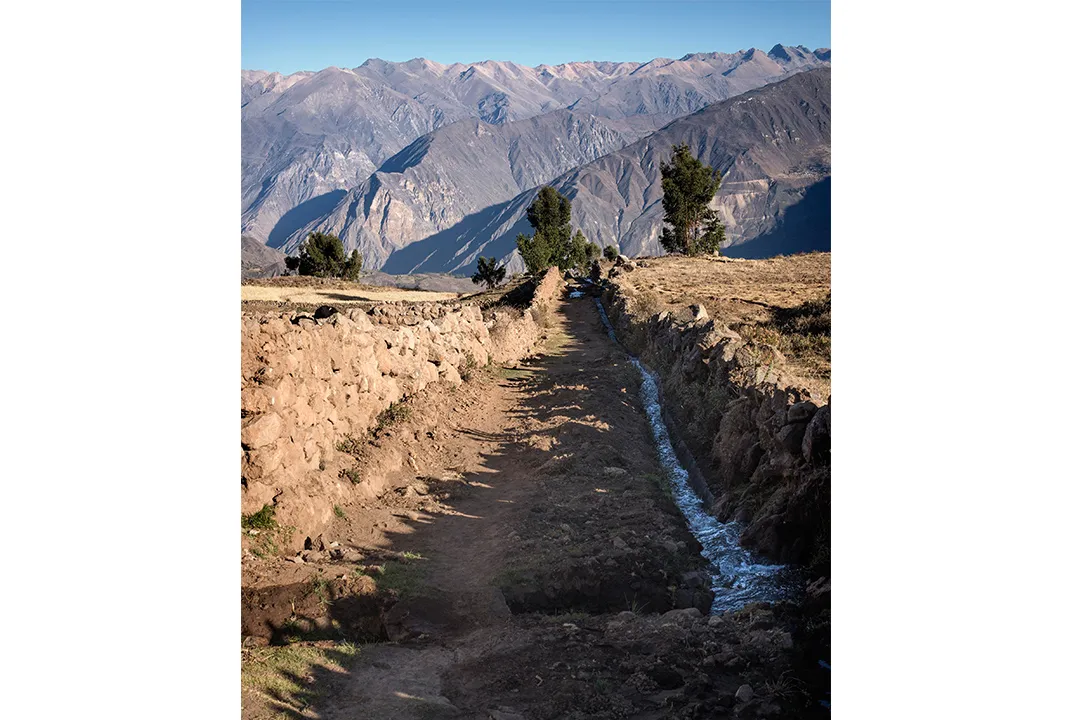

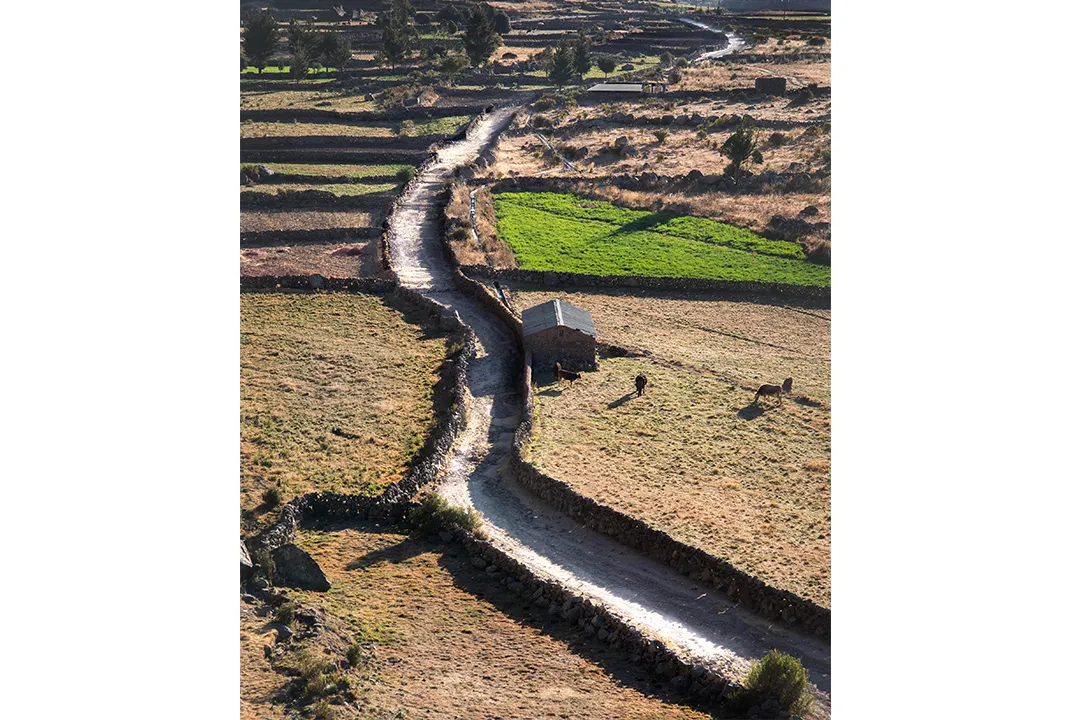

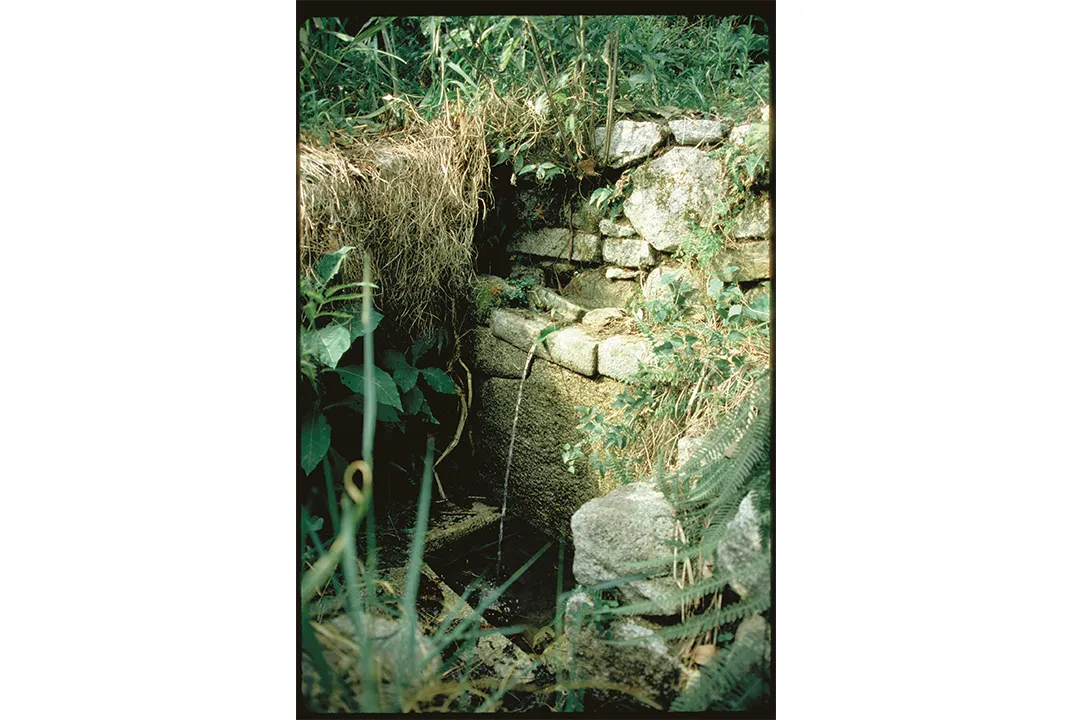

This monumental achievement, this vast ancient highway—known to the Inca, and today in Quechua, as Capac Ñan, commonly translated as the Royal Road but literally as “Road of the Lord”—was the glue that held together the vast Inca Empire, supporting both its expansion and its successful integration into a range of cultures. It was paved with blocks of stone, reinforced with retaining walls, dug into rock faces, and linked by as many as 200 bridges, like the one at Huinchiri, made of woven-grass rope, swaying high above churning rivers. The Inca engineers cut through some of the most diverse and extreme terrain in the world, spanning rain forests, deserts and high mountains.

At its early 16th-century peak, the Inca Empire included between eight million and twelve million people and extended from modern-day Colombia down to Chile and Argentina via Ecuador, Bolivia and Peru. The Capac Ñan linked Cusco, the Inca capital and center of its universe, with the rest of the realm, its main route and tributaries radiating in all directions. The largest empire in its day, it also ranked as among the most sophisticated, incorporating a diverse array of chiefdoms, kingdoms and tribes. Unlike other great empires, it used no currency. A powerful army and extraordinary central bureaucracy administered business and ensured that everyone worked—in agriculture until the harvest, and doing public works thereafter. Labor—including work on this great road—was the tax Inca subjects paid. Inca engineers planned and built the road without benefit of wheeled devices, draft animals, a written language, or even metal tools.

The last map of the Inca Road, considered the base map until now, was completed more than three decades ago, in 1984. It shows the road running for 14,378 miles. But the remapping conducted by Matos and an international group of scholars revealed that it actually stretched for nearly 25,000 miles. The new map was completed by Smithsonian cartographers for inclusion in the exhibition. Partly as a result of this work, the Inca Road became a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2014.

Before Matos became professionally interested in the road, it was simply a part of his daily life. Born in 1937 in the village of Huancavelica, at an altitude of some 12,000 feet in Peru’s central highlands, Matos grew up speaking Quechua; his family used the road to travel back and forth to the nearest town, some three hours away. “It was my first experience of walking on the Inca Road,” he says, though he didn’t realize it then, simply referring to it as the “Horse Road.” No cars came to Huancavelica until the 1970s. Today his old village is barely recognizable. “There were 300 people then. It’s cosmopolitan now.”

As a student in the 1950s at Lima’s National University of San Marcos, Matos diverged from his path into the legal profession when he realized that he enjoyed history classes far more than studying law. A professor suggested archaeology. He never looked back, going on to become a noted archaeologist, excavating and restoring ancient Andean sites, and a foremost anthropologist, pioneering the use of current native knowledge to understand his people’s past. Along the way, he has become instrumental in creating local museums that safeguard and interpret pre-Inca objects and structures.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/22/be/22be931d-acbe-4159-b7a3-4cb7e518e407/matosweb.jpg)

Since Matos first came to the United States in 1976, he has held visiting professorships at three American universities, as well as ones in Copenhagen, Tokyo and Bonn. That’s in addition to previous professorial appointments at two Peruvian universities. In Washington, D.C., where he’s lived and worked since 1996, he still embraces his Andean roots, taking part in festivals and other activities with fellow Quechua immigrants. “Speaking Quechua is part of my legacy,” he says.

Among the six million Quechua speakers in South America today, many of the old ways remain. “People live in the same houses, the same places, and use the same roads as in the Inca time,” Matos says. “They’re planting the same plants. Their beliefs are still strong.”

But in some cases, the indigenous people Matos and his team interviewed represent the last living link to long-ago days. Seven years ago, Matos and his team interviewed 92-year-old Demetrio Roca, who recalled a 25-mile walk in 1925 with his mother from their village to Cusco, where she was a vendor in the central plaza. They were granted entrance to the sacred city only after they had prayed and engaged in a ritual purification. Roca wept as he spoke of new construction wiping out his community’s last Inca sacred place—destroyed, as it happened, for road expansion.

Nowadays, about 500 communities in Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia and northwestern Argentina rely on what remains of the road, much of it overgrown or destroyed by earthquakes or landslides. In isolated areas, it remains “the only road for their interactions,” Matos says. While they use it to go to market, it’s always been more than just a means of transport. “For them,” Matos says, “it’s Mother Earth, a companion.” And so they make offerings at sacred sites along the route, praying for safe travels and a speedy return, just as they’ve done for hundreds of years.

That compression of time and space is very much in keeping with the spirit of the museum exhibition, linking past and present—and with the Quechua worldview. Quechua speakers, Matos says, use the same word, pacha, to mean both time and space. “No space without time, no time without space,” he says. “It’s very sophisticated.”

The Quechua have persevered over the years in spite of severe political and environmental threats, including persecution by Shining Path Maoist guerrillas and terrorists in the 1980s. Nowadays the threats to indigenous people come from water scarcity—potentially devastating to agricultural communities—and the environmental effects of exploitation of natural resources, including copper, lead and gold, in the regions they call home.

“To preserve their traditional culture, [the Quechua] need to preserve the environment, especially from water and mining threats,” Matos emphasizes. But education needs to be improved too. “There are schools everywhere,” he says, “but there is no strong pre-Hispanic history. Native communities are not strongly connected with their past. In Cusco, it’s still strong. In other places, no.”

Still, he says, there is greater pride than ever among the Quechua, partly the benefit of vigorous tourism. (Some 8,000 people flocked to Huinchiri to watch the bridge-building ceremony in June last year.) “Now people are feeling proud to speak Quechua,” Matos says. “People are feeling very proud to be descendants of the Inca.” Matos hopes the Inca Road exhibition will help inspire greater commitment to preserving and understanding his people’s past. “Now,” he says, “is the crucial moment.”

This story is from the new travel quarterly, Smithsonian Journeys, which will arrive on newstands July 14.

"The Great Inka Road: Engineering an Empire" is on view at the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. through June 1, 2018."

The Great Inka Road: Engineering an Empire