How Do We Restore Trust in Our Democracies?

Museums can be a starting point, says David J. Skorton, the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution

:focal(802x440:803x441)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/41/b1/41b11343-3f22-4d17-90d3-bb10902ff110/saam-198412498_1_1.jpg)

Fatigued by years of a brutal civil war, divided by racial and economic strife, and fearful that immigrants were coming to take workers’ jobs, the United States’ long-term prospects were far from assured in 1867. In that contentious and chaotic environment, Frederick Douglass gave an impassioned speech in Boston about “our composite nation,” arguing for the virtue of a pluralistic United States. He wisely observed: “Trust is the foundation of society. Where there is no truth, there can be no trust, and where there is no trust, there can be no society.”

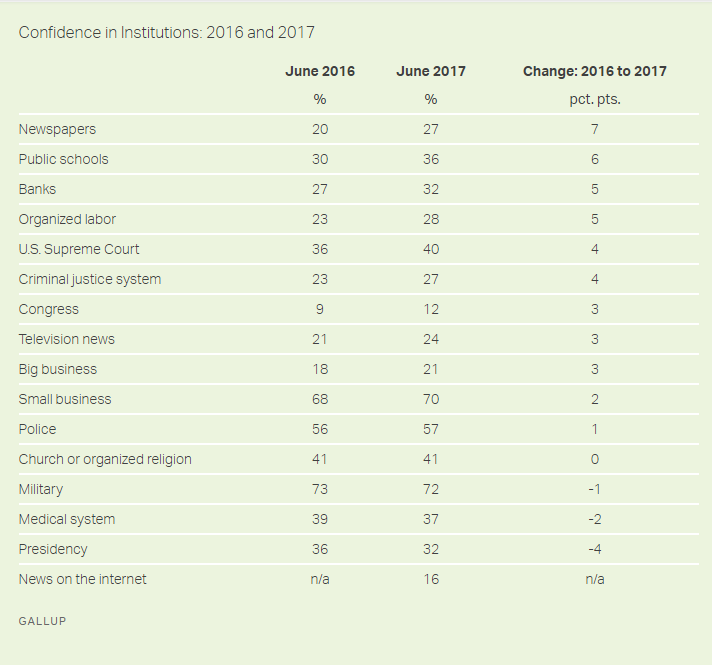

We find ourselves in a similar trust crisis today, not just in the United States, but around the world. Global confidence in many institutions is at a historic low. In the U.S., many people have lost faith in the very pillars of American civic identity, such as the government, academia, corporations and the media. There is a sense that these institutions are inadequately responsive to the needs of many. Although 2017 showed a slight uptick in confidence in institutions, of the 14 measured in a recent Gallup poll, only three—the police, the military and small business—ranked higher than 50 percent.

At the annual meeting in Davos, I heard many leaders from the public and private sectors describe the breakdown in trust in their own countries. Clearly, we must repair this trust if we are to mend a fractured world and build more broadly shared prosperity. But where to start? As secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, the world’s largest museum, research and education complex, I believe museums and cultural institutions can illuminate the path forward in our attempts to regain the public’s confidence in traditional democratic institutions.

Museums and libraries are in a strong position to do so because they remain among the most trusted public institutions in the United States and around the world. Because of their reputation as even-handed providers of unbiased information, museums can be public forums for people of different backgrounds and beliefs not only to learn and discover, but also to meet, discuss difficult subjects and build community.

I have seen how our museums and centres engage visitors and transform the way they see the world—especially our youngest visitors, who light up with the joy of new discovery. Through our education programs, we reach millions of national and international students, often using objects from our collections to demonstrate experiences and viewpoints that differ from what they might have encountered. By revealing history through the lens of diverse perspectives, museums humanize other cultures and contextualize present-day events and people.

As repositories of history, museums are also important symbols of collective identity. This is why Smithsonian curators, educators and researchers collaborate with other institutions around the world, facilitating reconciliation and healing where there has been conflict, and building an enduring trust within local communities and across different cultures and countries.

Science is another sphere where trust has waned. All scientific fields of study rely on hypothesis, observation and verification based on evidence, and yet many people are skeptical of the rigorous process that has led to advances in medicine, transportation, communications and myriad other areas. Science museums play a vital role in explaining the importance of the sciences to a general audience and showing them that the scientific method is largely responsible for the progress that underpins modern civilization. These museums also can illustrate the never-ending nature of scientific inquiry, helping all to understand why discovery is a nonlinear path.

Cultural institutions and museums create virtual and physical spaces to engage in conversation outside our own political, social and cultural circles. They are places where people of different backgrounds, religions and ethnicities can engage about topics that are often contentious or even taboo.

In 2014, for example, after the protests in Ferguson, Missouri, following the fatal shooting of the African American teenager Michael Brown by a police officer, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture convened a conversation about race, justice and community activism. Its central question, “What does this moment mean for America?” has inspired conversation in the years since, as we continue to bring together artists, faith communities and community leaders to take part in creative expressions about social justice.

That spirit guides many Smithsonian efforts to generate dialogue, such as the National Museum of American History’s collaboration with the nonprofit Zócalo Public Square and Arizona State University to create events and online conversation about what it means to be American, along with Smithsonian Second Opinion, a series of conversations with thought leaders on our website. I look forward to more dialogue led by cultural institutions because I fervently believe that respectful and open discussion with people who have opposing viewpoints can lead to solutions to our biggest challenges.

Museums also have a responsibility to challenge the public’s expectations by addressing uncomfortable truths. Trusted institutions like ours have the unique potential and responsibility to coax visitors out of their comfort zones, laying the groundwork for fact-based conversation that could lead to social and civic progress.

In February 2017, for instance, the National Museum of the American Indian and the National Museum of African Art presented From Tarzan to Tonto, a program examining some pervasive stereotypes in U.S. culture. This public-private sector collaboration brought together diverse audiences in a trusted setting to discuss these potentially divisive truths. At the former museum, the recently opened "Americans" exhibition pushes us to examine our own preconceived notions and implicit biases by presenting a question: “How is it that Indians can be so present and so absent in American life?”

When the United States Congress chose the National Mall in Washington, D.C., as the site of the Smithsonian 171 years ago, they boldly declared that trustworthy information about science, the arts and the human experience is central to the country's character and success. It is as true for other nations as it is for the U.S. I encourage everyone to look to museums and cultural institutions as exemplars of the honesty, openness and diversity that drive democracy. We are ideally suited to hold meaningful conversations and build the type of understanding that will help us realize not just Douglass’s vision of a “composite nation,” but a composite community of nations, built on our shared principles and a bedrock of trust.

This article was originally published by the World Economic Forum.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Skorton_350dpi.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Skorton_350dpi.jpg)