How Did Smithsonian Curators Pack 200 Years of African-American Culture in One Exhibition?

The curators of the Cultural Expressions exhibition collected stories and artifacts and brilliantly packed 200 years into one round room

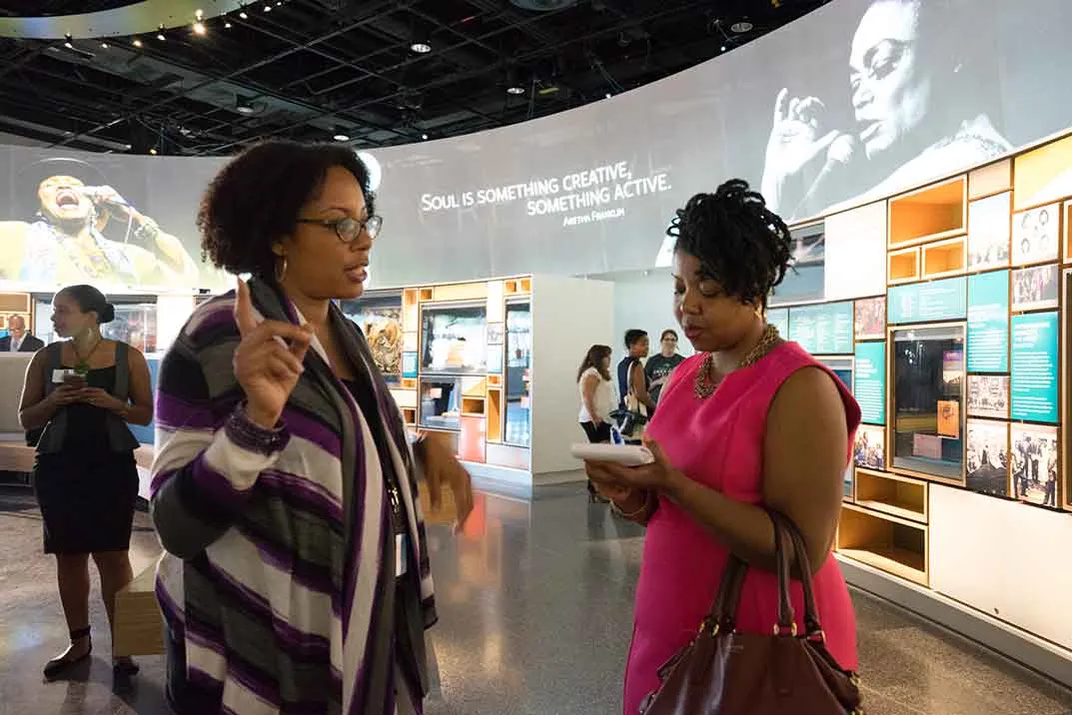

“Sometimes a collection tells you the story that it needs to tell,” says Joanne Hyppolite, a curator of the Cultural Expressions gallery at the new National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Hyppolite and co-curator Deborah Mack were given a task that no person has ever taken on before. In the finite space of one unusual gallery, they were asked to plan, collect and display an exhibition on the impossibly huge subject of the cultural expressions of African-Americans.

Their canvas was a round room on the museum's fourth floor. In it, case displays are organized in concentric circles beneath a high orbit of curved video screens projecting dance, theater, poetry and other performances.

This doesn't look like any other place, anywhere.

Clothes, hairstyles, painting, carving, cooking, gesture, dance, language etc. Nearly everything that human beings do is a cultural expression. Somehow, Hyppolite and Mack had to boil down hundreds of years of this vast subect and synthesize it into a single, circular gallery, where millions of people would come to walk through and learn from, while also perhaps seeing something of themselves. They would do this by choosing objects and arranging them into stories.

“One of the major ideas in this exhibition is that African-American culture is an everyday thing,” says Mack. “It doesn't have to be removed—it is very much a part of it. People grow up with it and take it for granted. At least some of these collections were celebrating the everyday, not the celebrity.”

Objects used to style black women's hair throughout the 20th century were thus grouped into a small collection. Devices that straightened or curled. Things remembered from mothers and grandmothers.

“Our museum has a policy that we have to see the object in person before accepting it,” says Hyppolite of the process it took to travel the country and meet with the people in their homes and in their churches, at their jobs and in their community spaces to gather the material of this exhibition.

“You are in someone's kitchen, in their work place,” adds Mack.

In these intimate places, Hyppolite and Mack asked strangers for family heirlooms. Styling tools and cookbooks and an oyster basket and more. It was time for these ordinary objects from the lives of black families to take on a role far beyond what they had originally been made for. It took little convincing.

“People feel honored,” says Hyppolite. “They understand the connection that this item has to the rest of the culture.”

“In every case they understood,” said Mack. “We didn't have to explain that connection. They understood it. When we said what the story line was, it was like 'of course.' There would be a question of whether to donate it or to loan it. But they could often finish our sentences.”

A trophy awarded to a debate team at Texas Southern University was one such item. TSU was the first debate team to integrate forensics competitions in the American south in 1957. Barbara Jordan, the first female black southerner elected to Congress, happened to be on that team as a student.

“They had the trophy sitting in the trophy case with dozens of others” says Hyppolite. “But it doesn't share that story with a larger world.”

The trophy soon after was shipped to Washington, D.C. to become part of the museum's collections.

The two curators approached Mary Jackson, a renowned basket weaver from Charleston, South Carolina, who has both preserved and elevated the art of basket-weaving that was brought to the region by West African slaves and maintained by the unique Gullah culture of South Carolina and Georgia's coasts.

“We commissioned two sweetgrass baskets from her,” says Mack. “She comes out of a historical community. She is a recognized artist. . . I went to meet her and told her what this story line is about and talked about what she would make that reflected the story line and values. She suggested that she create what was a working man's basket for transporting rice in the 18th century. But it was a working basket. It looks very much like the historic form.”

That was the first of two baskets that Jackson wove for the Museum.

“Her other piece is sculptural, says Mack. “It is an innovative form that nobody else can create. That was her 21st-century looking-forward form. Art for art's sake as opposed to art for function. I met with her several times, once in her studio where she does a lot of work now and another time with her daughter and husband. She knows what she is doing and where it comes from. She is a fourth-generation basket maker... She is a humbling presence. A great person.”

“Then there are the people you meet through their work alone and the stories about their work, since they lived so long ago,” says Hyppolite. “Like the story of Hercules, George Washington's cook. The foodways exhibit is talking about the diversity of food styles. It's not just soul food. You read about Hercules and you find that he is planning state diners, a celebrated French chef. His work is so appreciated that he is brought to Philadelphia. And he ran away.”

“He was a celebrity chef in his own day,” agreed Mack. “George Washington was able to avoid emancipating his staff by moving them from Mount Vernon to Philadelphia [the temporary capitol of the United States at the time] but moving them back and forth every six months. One of the times he was about to send his staff back, Hercules disappeared and was never seen again. Washington sent bounty hunters after him, posted rewards, but he was never heard from. Even today.”

The very first item to enter the collections of the museum and which is now on display is an Ecuadorian boat seat. It is a favorite of both curators. It came to the museum in the hands of Afro-Ecudorian Juan García Salazar.

Salazar grew up in a remote area of Ecuador, which isn't the first place most people would think of as part of the African diaspora. Salazar was part of a descendant community of Maroons, which are cultures of people descended from escaped African slaves who disappeared into the jungle to follow the ways of, and often intermarry with, Native Americans.

Salazar's Maroon grandmother would carry a carved wooden boat seat on visits to him, brought to make long journeys over water more comfortable. The web-like carvings on the boat seat are references to the traditional Anansi folk stories, represented by a spider, and told throughout Africa, South America and the Southern U.S.

“So he brings this boat seat that his mother has given him. And he goes to Lonnie Bunch's [the founding director of the museum] office and tells these incredible stories. And he donates it to us.”

“We wanted to also look into African diaspora cultures,” says Hyppolite. “Some of whom are now a part of the richness and diversity of African-American culture.”

Hyppolite and Mack collected more than they can ever have room to display in the museum at any one time. Objects will be rotated out to create new experiences for returning visitors. Digital collections will still allow access to items in storage. Future curators in centuries to come will have a deep reservoir of objects to draw on as they put together new exhibitions that tell new stories as African-American history continues to be made and African-American cultures continue to evolve.

Hyppolite thinks that the exhibition, and the culture it represents, will continue to be relevant for generations to come.

“Our culture functions as a bulwark,” Hyppolite says. “Like a defensive wall in a stockade. We'll continue to draw on it for a variety of purposes that range from survival to resistance and to sources for creative inspiration.”

"Cultural Expressions" is a new inaugural exhibition on view in the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Timed-entry passes are now available at the museum's website or by calling ETIX Customer Support Center at (866) 297-4020. Timed passes are required for entry to the museum and will continue to be required indefinitely.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JacksonLanders.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JacksonLanders.jpg)