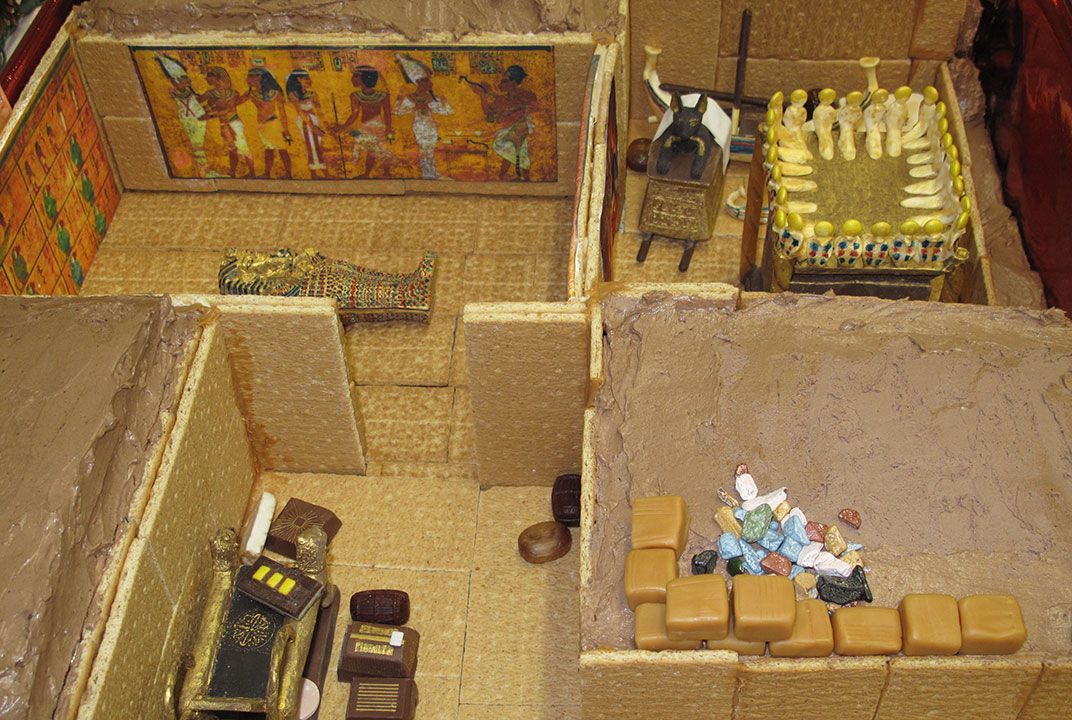

How an Archaeologist Revived King Tut’s Tomb With A Chocolate Cake

By day Eric Hollinger is an archeologist, but his passion is baking and his chocolate cakes are works to behold

Once a year, archaeologist Eric Hollinger bakes a cake. Not just any cake, an epic cake. Hollinger who works in the repatriation office at the National Museum of Natural History helping American Indian tribes reunite with sacred objects, is equally regarded for crafting intricate cakes inspired by the museum's exhibitions and research.

It all started nearly a dozen years ago with a potluck. Why not something with an archaeological theme, Hollinger told his wife Lauren Sieg, an archaeologist working at the National Museum of the American Indian. So the couple crafted a Mississippian Temple Mound excavation site. They used 14 separate cakes and made a blue river out of Jell-O. Staff were encouraged to excavate the site as they ate the cake.

Now an annual tradition, Hollinger's culinary confections have represented places domestic and international, from an Aztec calendar stone carved entirely from a block of chocolate to a Mandala, or Tibetan sand painting. Each year, Hollinger keeps the cake's subject a secret. "We always try to keep people guessing," he says. "We want to always push the envelope."

A lifelong baking enthusiast (whose childhood aspiration, he says, was to become a baker) Hollinger has expanded his arsenal of technique as the years have gone by. Working with chocolate is a huge part of creating the cakes. When he carved the elephant from the museum's rotunda out of a huge block of chocolate, he struggled to attach the bull elephant's enormous trunk. When he used chocolate to craft the Aztec calendar stone, he used a nail to carve the intricate details. Chocolate is a difficult medium to work in, Hollinger says, because it's rather temperamental: it must be tempered, or heated, cooled and reheated, or else it turns white and chalky. And because chocolate melts, Hollinger is often working clumsily wearing oven mitts to protect the chocolate from the heat of his hands; and he can only work in small bursts before returning the chocolate back to the refrigerator.

A few years back, Hollinger and his wife took a trip to Hawaii; in 2014, that trip resurfaced in the form of the 2014 holiday cake, honoring the archaeological site Pu`uhonua O Hōnaunau, where Hawaiians accused of crimes used to go to seek refuge. The cake even included a volcano with flowing chocolate lava.

"It's kind of a challenge to envision making a site with something edible," Hollinger says. "You end up tapping parts of your education and experience you never thought you'd need, and end up applying it in a very strange context."

Hollinger and his wife begin constructing parts of the cakes months in advance, using holiday visits to family members as a chance to recruit young relatives into the process. In 2008, when Hollinger began to recreate the terracotta army from the tomb of the first Emperor of China, his nieces helped him cast more than a hundred tiny chocolate soldiers. To create the Tibetan Mandala, Hollinger used a bent plastic straw and edible sand to recreate, as faithfully as possible, the technique used by monks. It took him 27 hours to delicately rasp the straw with the pencil, depositing, a few grains at a time, sand made of colored sugar onto the cake.

Faithfully representing the site or the research work by the museum's scientists is a crucial piece of the puzzle for Hollinger, who consults with curators and researchers if a cake falls into their area of expertise. The cake's curatorial team is sworn to secrecy, and theme or subject of the cake is never revealed until the day the cake is unveiled at the annual staff holiday party held by the anthropology department. "It started as a way to raise morale and inspire people in our department, but now that it's being seen far beyond," Hollinger says, noting that within minutes of revealing the Mandala, colleagues had sent pictures of the cake to friends as far as Uzbekistan. "If it excites people about anthropology and archeology," he says, "that's a great reason to do it."

So far, the cakes have been a special treat for those at working at the museum, but their growing popularity has Hollinger and the museum officials looking for ways to get the public involved, whether through a demonstration or some kind of educational programming. "We hope that this approach, and these projects we've done, can serve as inspiration for others to challenge themselves to see what they can do with food, especially as a way to get kids interested in a food or an ancient archaeological site."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)