The Great Moon Hoax Was Simply a Sign of Its Time

Scientific discoveries and faraway voyages inspired fantastic tales—and a new Smithsonian exhibition

:focal(541x239:542x240)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5a/c0/5ac078a1-b4c9-4a12-afb3-66f32ec9589e/3galluzzo1web.jpg)

Anyone who opened the pages of the New York Sun on Tuesday, August 25, 1835, had no idea they were reading an early work of science fiction—and one of the greatest hoaxes of all time.

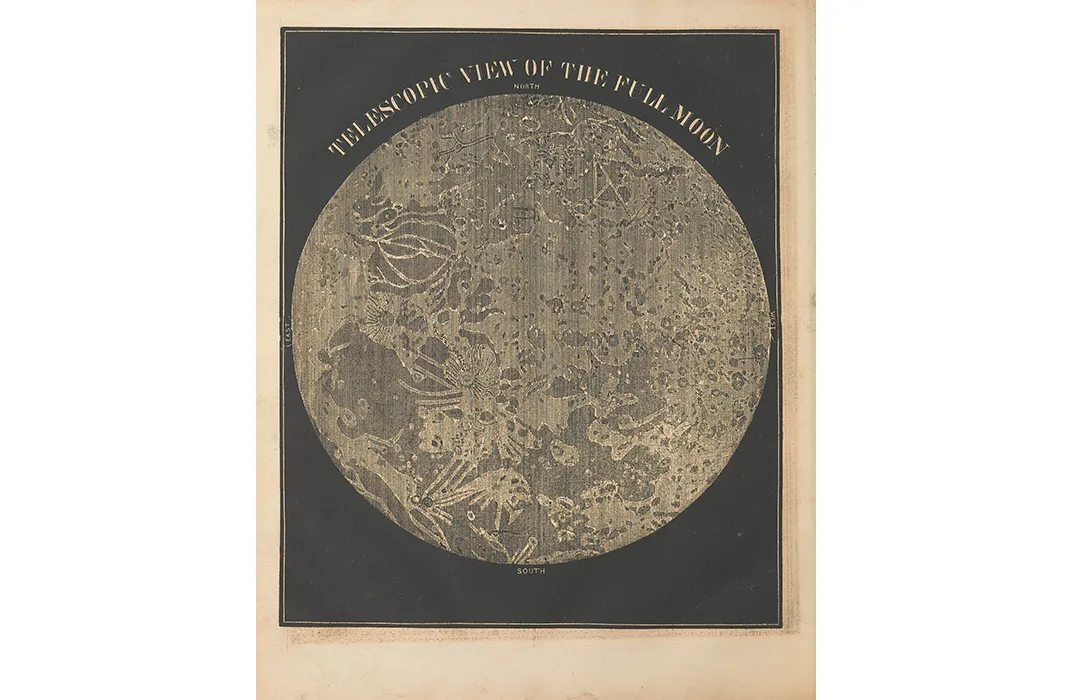

In that issue began a six-part series, now known as the Great Moon Hoax, that described the findings of Sir John Herschel, a real English astronomer who had traveled to the Cape of Good Hope in 1834 to catalog the stars of the Southern Hemisphere. But according to the Sun, Herschel found far more than stars through the lens of his telescope.

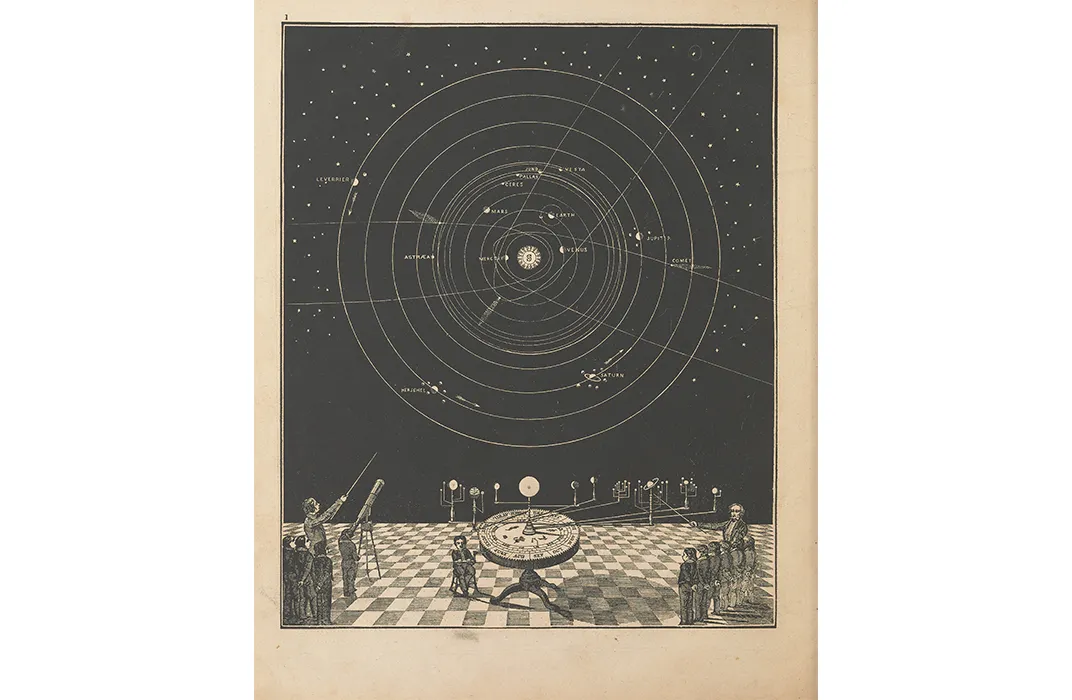

The 19th century was “the time before we knew everything,” says Kirsten van der Veen of the Smithsonian Institution’s Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology. “Science was very accessible,” she says. Common people of the time could easily read about scientific discoveries and expeditions to far-off places in the pages of newspapers, magazines and books. So the Herschel tale was not an odd thing to find in the daily paper. And that the series was supposedly a supplement to the Edinburgh Journal of Science leant it credibility.

But careful readers could have picked up hints early on that the story was unreal. On the first day, for example, the author claimed that Herschel had not only discovered planets outside our solar system and settled once and for all whether the moon was inhabited but also “solved or corrected nearly every leading problem of mathematical astronomy.” The story then described how Herschel had managed to create a massive telescope lens 24 feet in diameter and 7 tons in weight—six times larger than what had been the largest lens to date—and carted it all the way from England to South Africa.

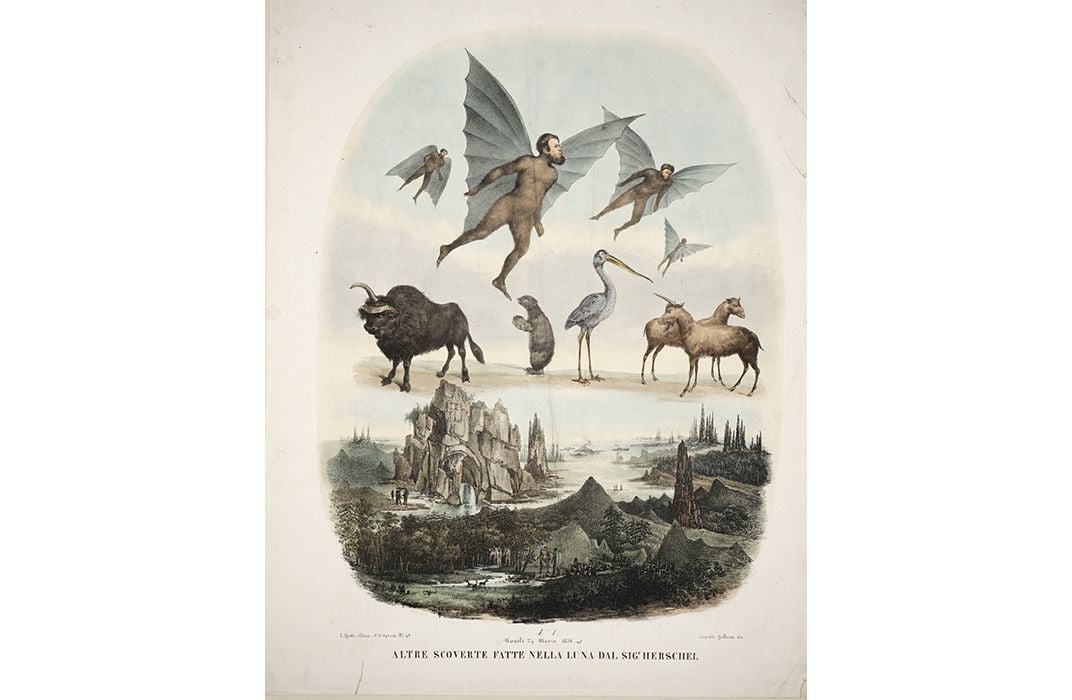

Then the tale began to delve into the lunar discoveries made with the colossal telescope: First there were hints of vegetation, along with a beach of white sand and a chain of slender pyramids. Herds of brown quadrupeds, similar to bison, were found in the shade of some woods. And in a valley were single-horned goats the bluish color of lead.

More animals were documented in part three, including small reindeer, mini zebra and the bipedal beaver. “It carries its young in its arms like a human being, and moves with an easy gliding motion.” But the real surprise came on day four: creatures that looked like humans, were about four feet tall—and had wings and could fly. “We scientifically denominated them as Vespertilio-homo, or man-bat; and they are doubtless innocent and happy creatures,” the author wrote.

Like the 1938 radio program based on H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds, the stories in the New York Sun had not been published as an attempt to fool anyone, but the writer “underestimated the gullibility of the public,” van der Veen says. Years later, after confessing to authorship of the series, Richard Adams Locke said that it was meant as a satire reflecting on the influence that religion had then on science. But readers lapped up the tale, which was soon reprinted in papers across Europe. An Italian publication even included beautiful lithographs detailing what Herschel had discovered.

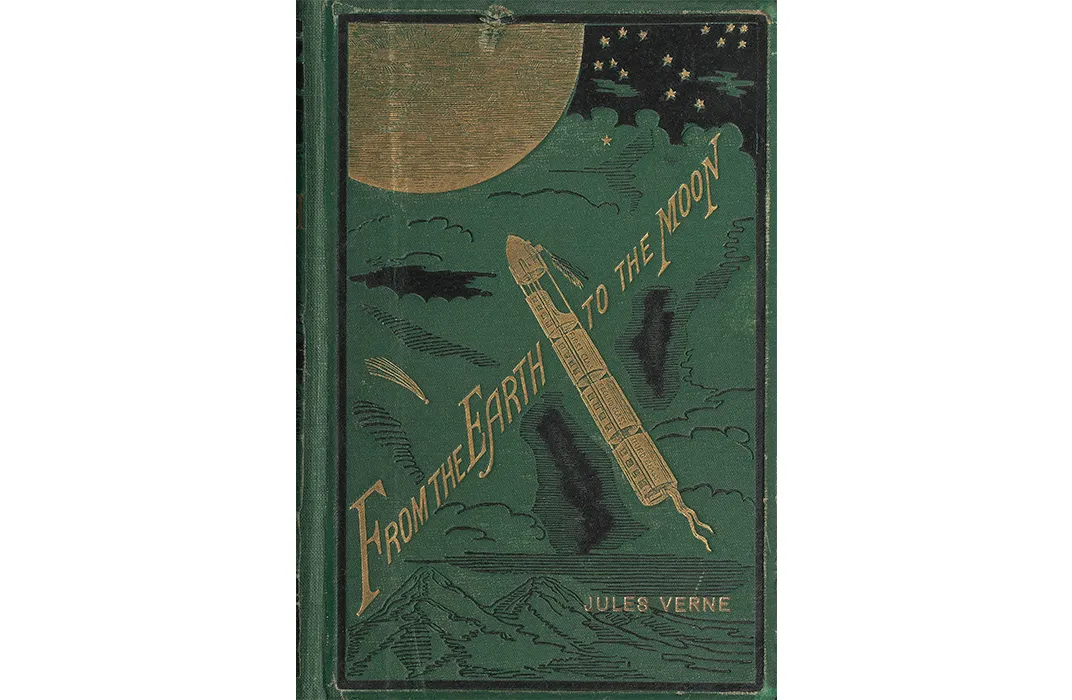

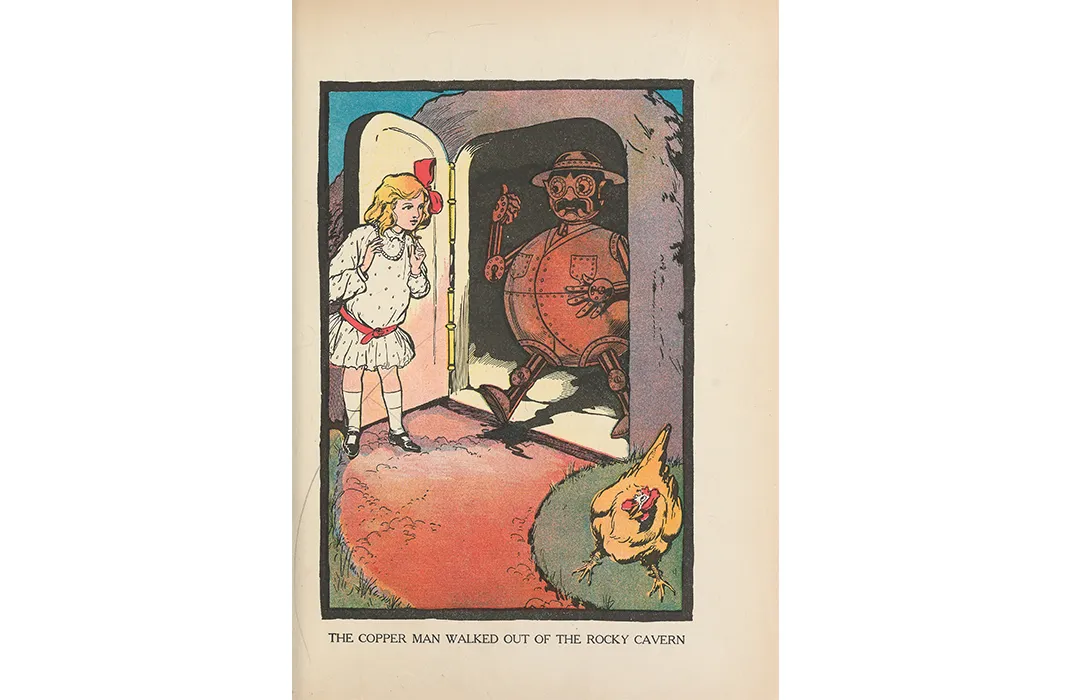

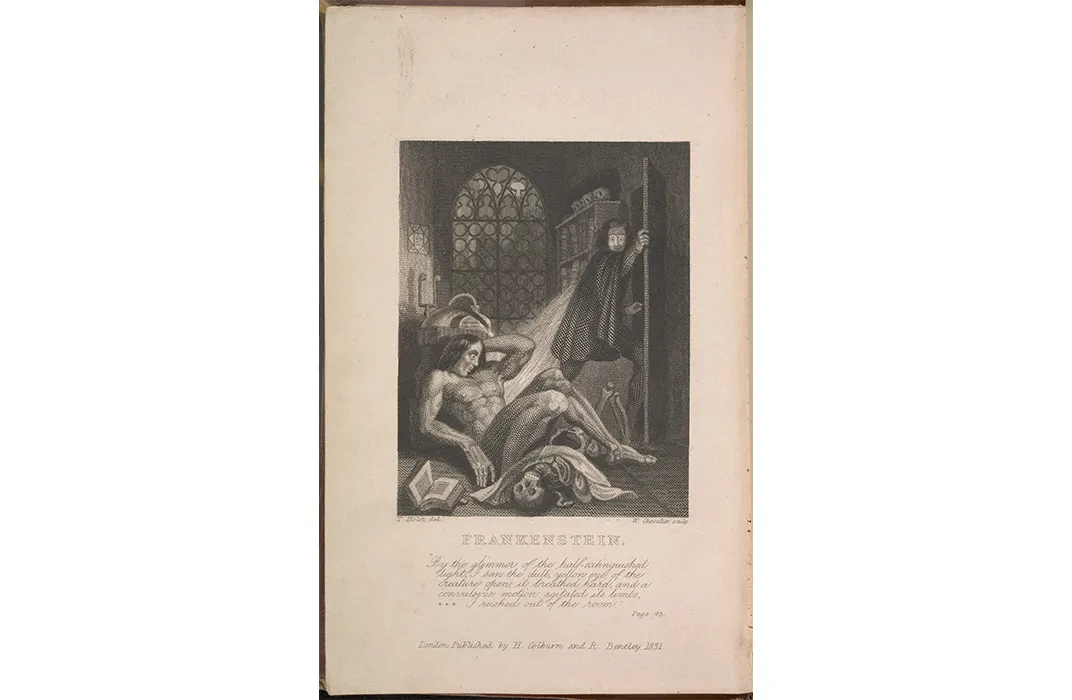

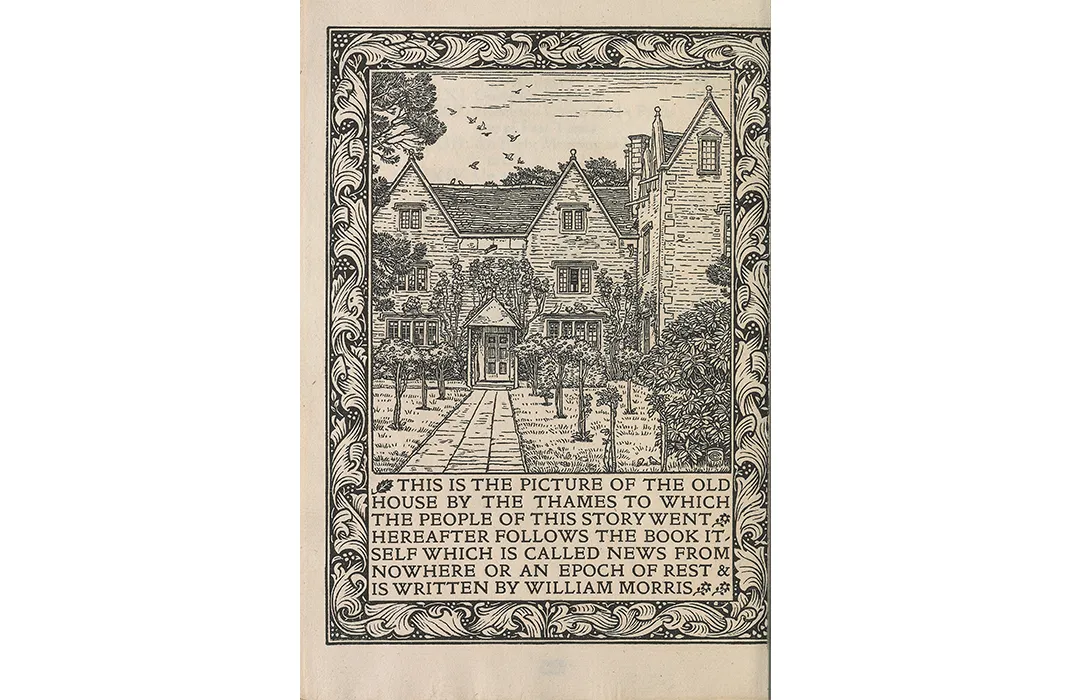

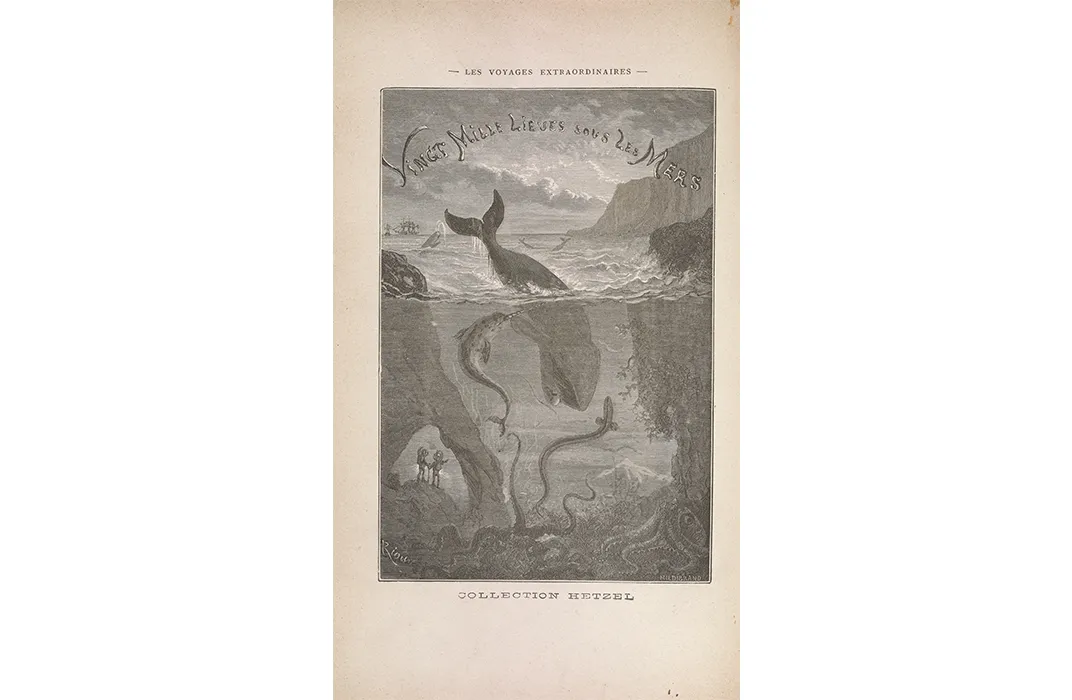

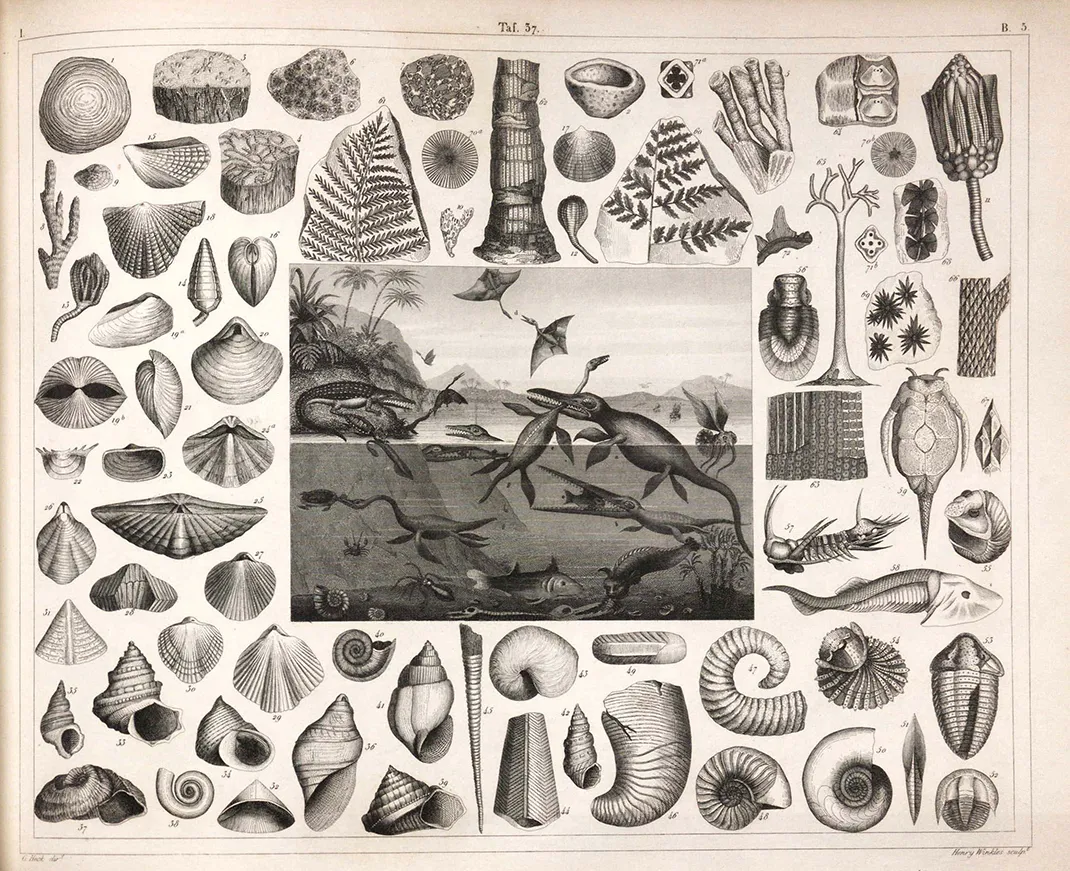

One of those lithographs is now on display at the Dibner’s new gallery at the National Museum of American History in the exhibition “Fantastic Worlds: Science and Fiction 1780-1910,” along with illustrations from the works of Jules Verne, Mary Shelley and L. Frank Baum, (a sampling of the exquisite offerings is included below).

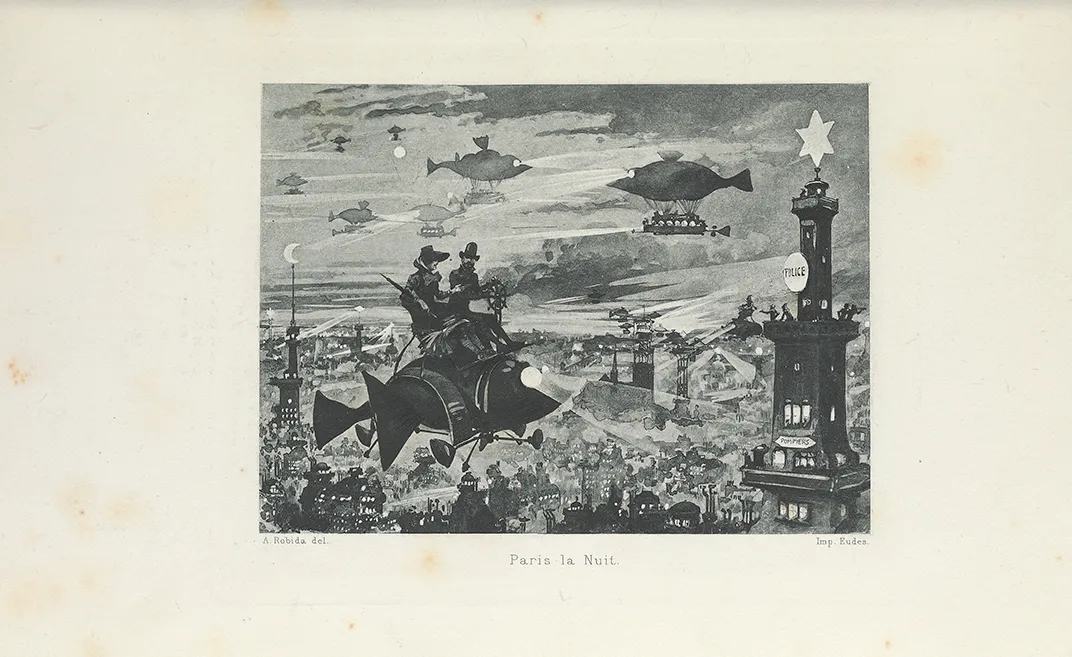

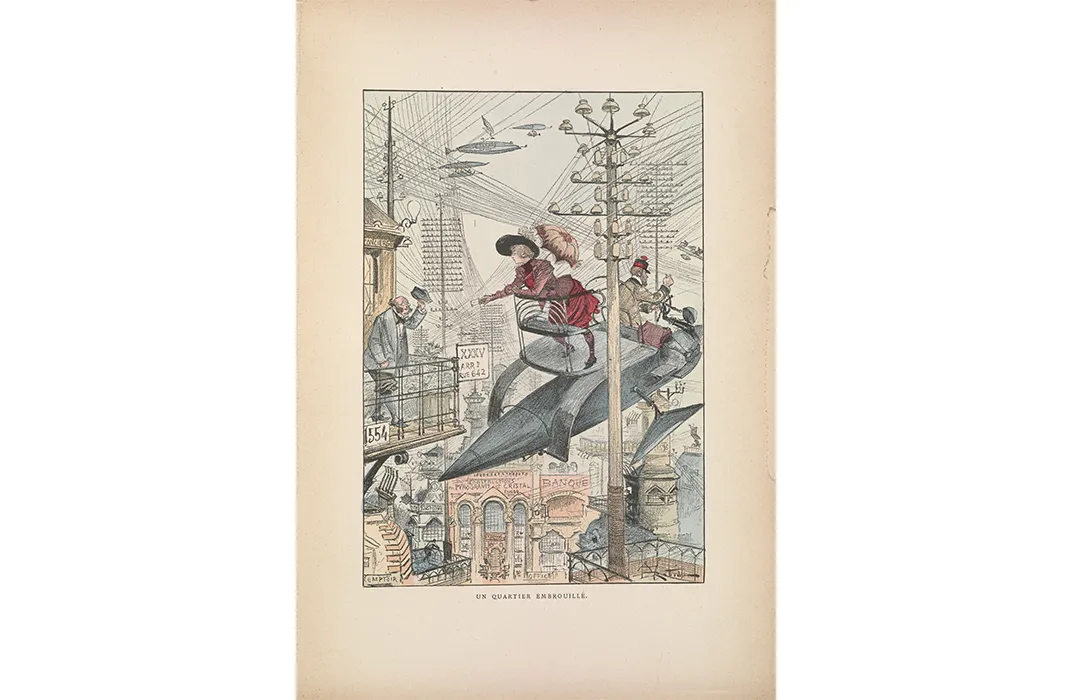

“In the years between 1780 and 1910, scientific disciplines were coming into their own, and whole new frontiers of discovery were emerging,” says Doug Dunlop of the Smithsonian Libraries. “The public was engaged with science at an unprecedented level. Fiction writers were inspired, too, preemptively exploring these new worlds, using science as a springboard.”

And Locke was not the only writer to perpetuate a hoax on an unsuspecting readership. Shortly before Locke’s story appeared in the Sun, Edgar Allan Poe wrote his own tale, “The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall,” which was published in the June 1835 issue of the Southern Literary Messenger. Poe later accused Locke of stealing his idea. That isn’t certain, but Poe’s story did inspire—and even appear in—Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon.

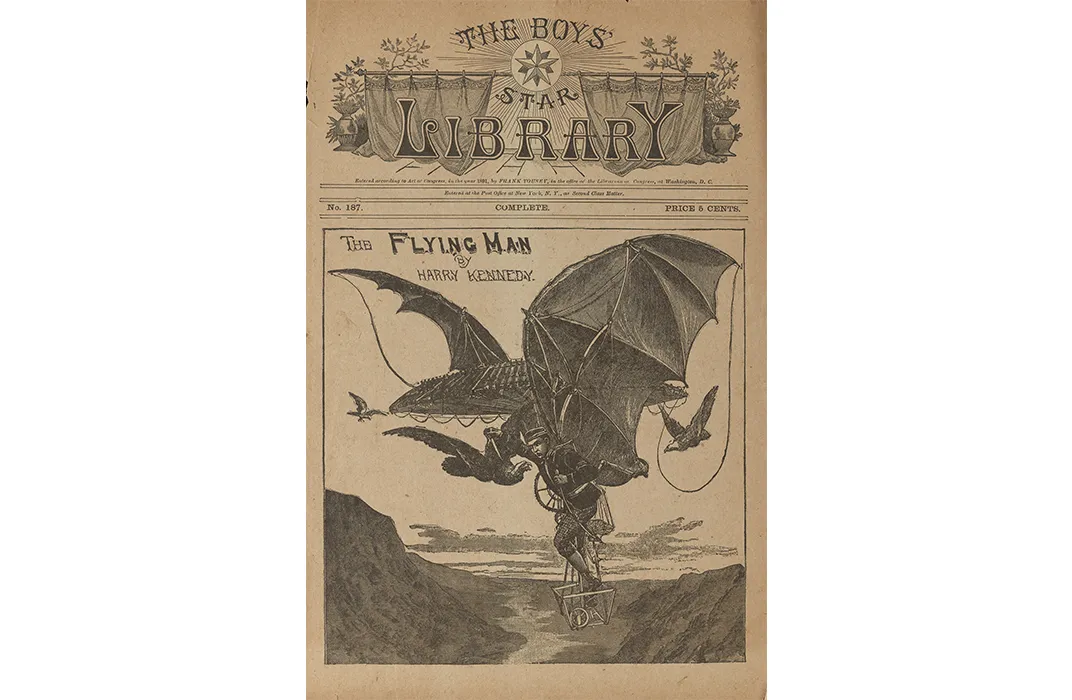

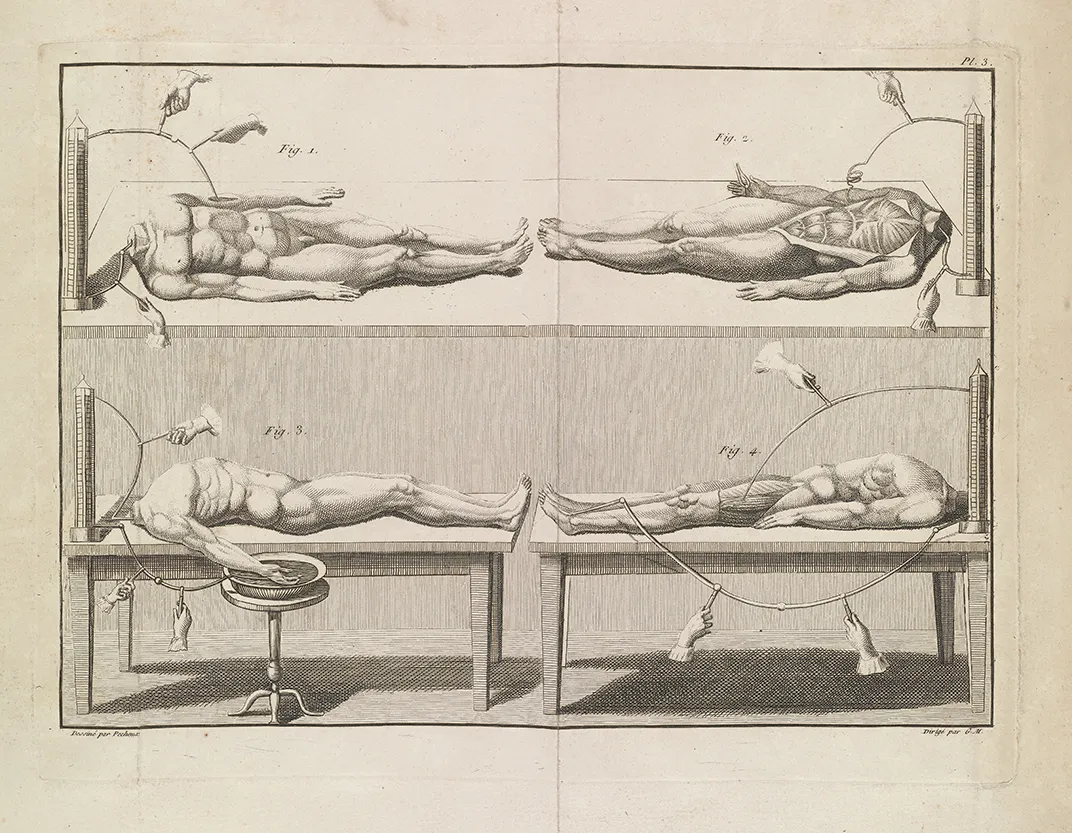

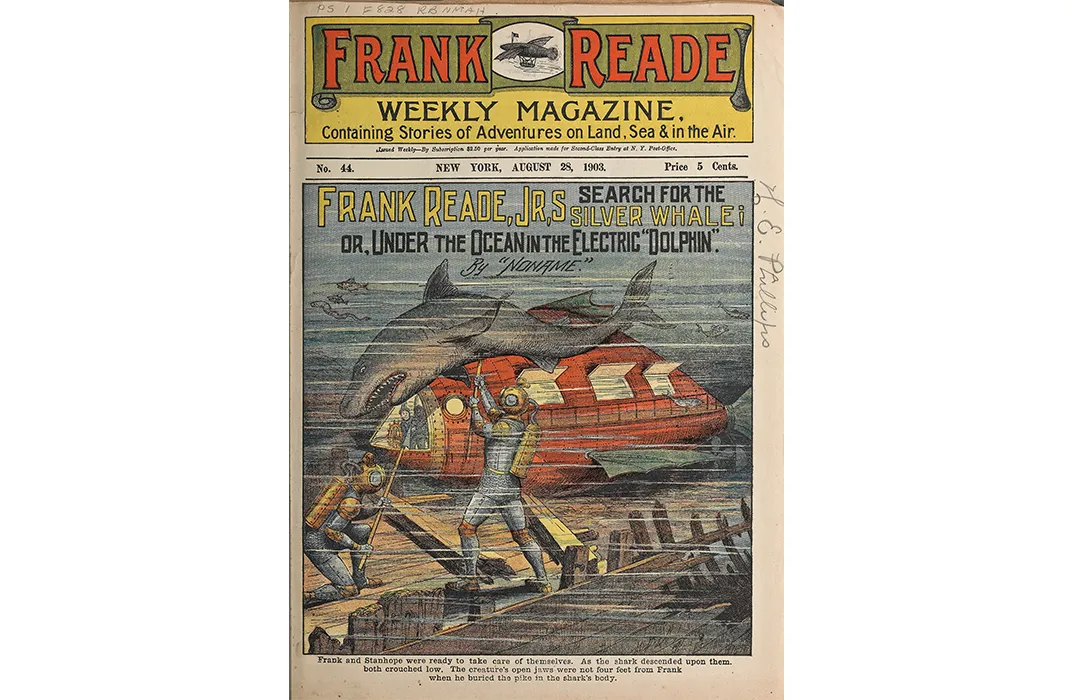

Similar to how the science of black holes informed the 2014 blockbuster Interstellar, discoveries of that period inspired writers during this time, though most, including Verne, labeled their works as fiction. Mary Shelley, for instance, incorporated the science of surgeon Luigi Galvani into her novel Frankenstein. In the late 1700s, Galvani had experimented with electricity on animals. And those readers that didn’t want to tackle an entire book could turn to illustrated dime novels such as the Frank Reade Weekly Magazine—several issues of which are on display at the museum.

“Through this exhibition, we want to highlight the impact of scientific discovery and invention,” says Dunlop, “and we hope to bridge the gap between two genres often seen as distinct.”

"Fantastic Worlds: Science Fiction, 1780-1910" is on view through October 2016 at the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e2/37/e2377d4e-ae6c-4b20-a4b2-dfc269990425/3flammarionweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fd/aa/fdaaff07-d1bd-4a94-81d7-65df95024f88/3munchausenweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/65/6e/656e6729-1998-478c-a4cd-a3a8b1708201/4baum1web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)