Early Films (Including One by Thomas Edison) Made Yoga Look Like Magic

The Sackler Gallery exhibit shows how yoga went from fakery to fitness in the West

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20131118084037hindoo-fakir.jpg)

To Americans living in the late 19th century, yoga looked an awful lot like magic. The ancient discipline appeared to Western observers primarily in the form of ethnographic images of “fakirs”—a blanket term encompassing Sufi dervishes, Hindu ascetics and, most importantly, stage and street performers of death-defying stunts, such as the bed-of-nails and Indian rope tricks. In 1902, the “fakir-yogi” made his big screen debut in a “trick film” produced by Thomas Edison, Hindoo Fakir, one of three motion pictures in the Sackler Gallery’s pioneering exhibition, “Yoga: The Art of Transformation.”

Hindoo Fakir, said to be the first film ever made about India, depicts the stage act of an Indian magician who makes his assistant disappear and reappear, as a butterfly emerging from a flower. To a modern eye, the special effects may leave something to be desired. But Edison’s audiences, in nickelodeons and vaudeville houses, would have marveled at the magic on screen as well as the magic of the moving image itself. Cinema was still new at the time and dominated by “actuality films” of exotic destinations and “trick films,” like Hindoo Fakir, which featured dissolves, superimpositions and other seemingly magical techniques. Indeed, some of the most important early filmmakers were magicians, including George Melies and Dadasaheb Phalke, director of India’s first feature film. “The early days of cinema were about wonder and showing off this technology,” says Tom Vick, curator of film at the Freer and Sackler galleries.

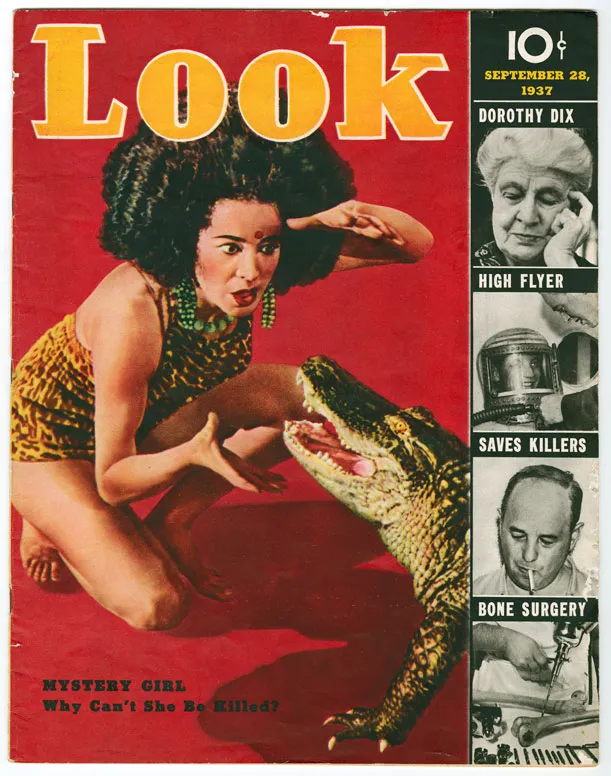

Early cinema was certainly not about cultural sensitivity. The similarity between “fakir” and “faker” is no coincidence; these words became synonyms in the American imagination, as performers in circuses and magic shows invoked supernatural powers commonly attributed to the fakir-yogi. Howard Thurston, a stage magician from Ohio, appropriated the Indian rope trick for his popular 1920s traveling show. In the 1930s, the French magician Koringa, billed as the “only female fakir in the world,” baffled audiences with hypnosis and crocodile wrestling. Her assumed Indian identity was an “understandable idea by that time,” says Sita Reddy, a Smithsonian Folklife research associate and “Yoga” curator. “The fakir became something that didn’t have to be explained anew; it was already circulating.” Fakir was, if not a household name, a part of popular parlance—pervasive enough that in 1931, Winston Churchill used it as a slur against Gandhi.

Yet Western taste for fakir-style huckstering appears to have waned by 1941, when the musical You’re the One presented the yogi as an object of ridicule. In a big band number called “The Yogi Who Lost His Will Power,” the eponymous yogi runs through all of the typical “Indian” cliches, wearing the obligatory turban and robes, gazing into a crystal ball, lying on a bed of nails and more. But the lyrics by Johnny Mercer cast him as a hapless romantic who “couldn’t concentrate or lie on broken glass” after falling for the “Maharajah’s turtle dove”; for all his yogic powers, this yogi is powerless when it comes to love. Arriving at the tail end of the fakir phenomenon, You’re the One encouraged audiences to laugh, rather than marvel, at the stock character.

How did yoga make the leap from the circus ring to the American mainstream? Reddy traces yoga’s current popularity to the loosening of Indian immigration restrictions in 1965, which brought droves of yogis into the U.S.—and into the confidence of celebrities like the Beatles and Marilyn Monroe. But the transformation began much earlier, she says, with the teachings of Swami Vivekananda, the Hindu spiritual leader whose 1896 book, Raja Yoga, inaugurated the modern era of yoga. Vivekananda denounced the conjurers and contortionists he felt had hijacked the practice and instead proposed a yoga of the mind that would serve as an “emblem of authentic Hinduism.” Vivekananda’s vision of rational spirituality contended with the fakir trope in the early decades of the 20th century, but after the 1940s, yoga was increasingly linked to medicine and fitness culture, gaining a new kind of cultural legitimacy in the West.

The physicality of yoga is revived in the third and final film of the exhibit, in which master practitioner T. Krishnamacharya demonstrates a series of linked asanas, or postures, which form the backbone of yoga practice today. This 1938 silent film introduced yoga to new audiences across the whole of India, expanding the practice beyond the traditionally private teacher-student relationship for the first time in history. Unlike Hindoo Fakir and You’re the One, the Krishnamacharya film was made by and for Indians. But like them, it affirms the power of the moving image to communicate the dynamism of yoga.