Azar Nafisi on Why the Arts and Humanities Are Critical to the American Vision

The author of “Reading Lolita in Tehran” and recipient of a Smithsonian award, discusses why in education art matters as much as science

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d3/f9/d3f9337e-4da1-47aa-b94b-5a08705a7226/portrait.jpg)

Born in Tehran as the daughter of the mayor, educated in Switzerland, with a PhD from the University of Oklahoma and a fellowship at Oxford, Azar Nafisi returned to Iran to teach literature in the late 1980s just as the Islamic revolution was clamping down.

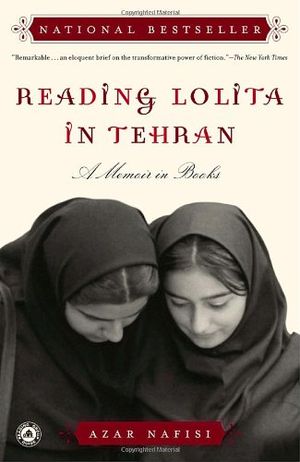

Fired for refusing to wear a headscarf, she conducted study groups at her home with a handful of students looking at some of her favorite writing. A book about that experience, Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books (2003), became an international sensation, with two years on U.S. bestseller lists and translated into 32 languages.

It also earned Nafisi a number of awards and honors, the latest of which comes this week with the 2015 Benjamin Franklin Creativity Laureate in the Humanities and Public Service from the Smithsonian Associates and Creativity Foundation.

The medal, which has previously gone to such varied recipients as Yo-Yo Ma, Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, Meryl Streep, Jules Feiffer and Mark Morris, will be presented this weekend. A public interview with the author is set for 7 p.m. Friday, April 10, at the Smithsonian’s S. Dillon Ripley Center on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

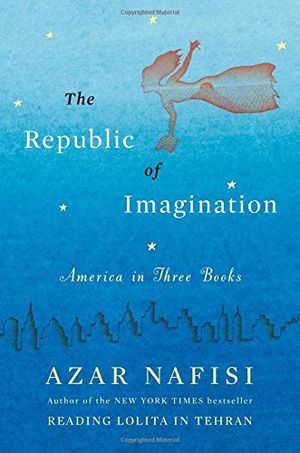

Nafisi, who transplanted to the United States in 1997, becoming a citizen in 2008, is a fellow at John Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies. Her latest book, The Republic of Imagination, extends her previous theme, combining deep reading of some of literature’s classic texts with impassioned personal narrative. She spoke with Smithsonian.com about her work and the honor this week.

Was Benjamin Franklin, namesake of this award, a particular hero of yours?

Benjamin Franklin I love. I love that his rather ‘ordinary’ appearance belies all the different aspects of him. Franklin for me was one of the best examples of curiosity and empathy. He did not differentiate between the curiosity and creativity that goes into science and wanting to know about the world, with the desire to know about the arts and humanities. He knew it was not separate, as many of our leaders seem to think today; that both go into the human spirit. I love that he looks so mischievous, doesn’t he? Like he has something in his pocket that he wants to spring on us.

This is a theme in some of your works: The focus on science and technology to the exclusion of literature and the arts.

Yes, it seems that so many leaders have the wrong view of humanities and science. You look at the Smithsonian Institution and you see it is the jewel in America’s eye for the fact it doesn’t segregate the kind of passion and precision that goes into science with that that goes into the arts; that they have these museums of natural history and American history right next to the art gallery and the Freer gallery. The Smithsonian celebrates the best achievements under one rubric.

What some of the leaders today do not understand is the crucial importance of humanities to our lives as a pragmatic matter. They don’t see the relationship between the scientific and the artistic; that engineering and technology would be shorn of any new ideas without the humanities. I think they should take another look at the Einstein statue in front of the National Academy of Sciences. He said: "Knowledge is limited, but imagination encircles the world."

Yet, you point out in The Republic of Imagination that so many curriculums have reduced arts and humanities teaching in favor of science or technology only.

This is so heartbreaking to me. It’s a matter I feel touches me not only in what I do as writer and reader, but also as an immigrant. In other parts of the world, including the one I am from, people are daily jailed and harassed for writing or reading a book, for drawing a painting that is not according to the government standards. You see people all over the world who are dying to go to museums for free, to enjoy music, and poetry, and literature, and now we’re depriving our schools of that.

One of the things the founders were fascinated with—Washington talks about the fact that they were the ones who were going to make Enlightenment ideas concrete. How can our children survive this world without imaginative knowledge? I mean, can you imagine anyone being a responsible citizen without knowing about the history and culture of this country, never mind the world?

You learned about the literature of America at an early age?

For me it began at home. At our home, the thing that we respected, my parents and my family as a whole, what they always focused on was education and especially for us, it was literature. So I was used to my father telling me stories since I was conscious of being a human being. I was 3-and-a-half or so. He would tell me bedtime stories and he would tell me stories from all over the world, not just from Iran. The point about Iran, both at that time and right now as we speak, is that it was a very cosmopolitan country. At least the parts of it where I grew up, and now because people have been deprived of that culture, they are striving for it much more. The films I saw along with millions of other kids, came from all over the world.

Why did you focus so intently on American literature?

One reason was my studies, my area of concentration was American lit. But also in those days, America, if you remember, in Iran was the Great Satan. And people always pay attention to the Great Satan.

There was this way of looking at America that was all very political, and all very ideological. And the way I show my students what this America was was through books. These books represented the best that America had to offer, but also offered a genuine and sincere critique of America, not like the rabid kind of criticism that the Islamic regime was feeding them, but a serious one.

I wanted my students to understand the world and understand America through the best that it had to offer and connect to that, and not just through politics. I didn’t want them to know America just through the people who were ruling over America at that time or what the Iranian television told them.

Were you surprised Reading Lolita in Tehran was such a bestseller?

It shocked me to tell you the truth. Most of my friends and some of my colleagues kept telling me that this book is really going to do poorly, because they said, ‘Everyone is focused on Iraq, and no one is going to be reading about Iran.’ And: ‘You are writing about writers that nobody cares about anymore.’ But I couldn’t help it. This is what I wanted to write about.

So, apart from my editors, who always believed in the book, in terms of it always selling well, I never for one moment believed—even when it went on the bestseller list—I still refused to acknowledge it.

A part of the reason I think the book became a success was that until then people had heard very little, if anything, about ordinary Iranian people, and the view of Iran since hostage taking was such a negative one. It was all about the regime. I think people all around the world, including in this country, they connected to these girls, they connected to these students, I think. They saw they had much more in common, than the way Iran was presented.

The second reason was literature. I really did not believe how much imagination connects you to people; that someone who loved Henry James or Jane Austin would want to share it, now that this book was out.

How did that success change your life or your direction?

I think it’s very difficult to take success of yourself too seriously and I really mean it. Sometimes I lose perspective because I really don’t believe I have achieved much, or that this book’s success should change me in an essential way. I always felt passionate about these things. I don’t remember a time where I was not passionate about reading and writing and, later on when I finished college, teaching. What it did for me, for which I’m very grateful, was two things. One, it gave me space to be able to write. When I was in Iran, my first book came out under severe censorship, and then it was never allowed to be published again. So here I very much appreciated the fact that I could tell any thing I wanted, and now because of this book’s success, people would want me to write more.

The most valuable thing, is that through my books, I have been connected to so many people.

That’s a theme of your books as well: How literature makes you feel less lonely, a way to connect to the world even when you’re by yourself.

Yes, you know there is a great quote from James Baldwin where he talks about the fact that you feel really lonely and miserable until you read about someone who lived 100 years before you did called Dostoyevsky. Then he says that all your misery and loneliness is alleviated when you realize that someone else has felt the same way you have. That quotation from Baldwin is very essential to my book, because he continues on to say: "Art would not be important if life were not important, and life is important."

So he connects art and life to one another, which is what I always want to tell our policymakers who are constantly cutting budgets for arts and humanities. Arts and humanities endured before you and I, and they will endure after you and I. And the reason they endure is because they matter to life.

You’ve been a U. S. citizen for a while. Do you feel like an American citizen now or do you feel like you are between two countries?

One of the great things about becoming an American citizen is that you can bring your past with you. Like, for example, I don’t feel that I leave behind those aspects of Iran that have come so close and become part of my DNA, because now I’m not just an American. I’m an Iranian-American.

I think this is what keeps America so vibrant and alive. People constantly coming to this country, and bringing with them their alternative ways of looking at America and thereby changing it. And this constant change is what keeps America healthy. Unfortunately, right now we are in a period of crisis, which is not just political or economic, it’s a crisis of vision. If one day we decided to have an America that is homogeneously one way or another, then I think I would feel homeless again.

There is a cash prize with this award, will that afford you to do anything special that you’ve wanted to do?

Right now, there’s this project in my mind which I hope will come to fruition which is about trying to create a forum where young people, and especially young people in community colleges and in public high schools, whose access to ideas and information has been cut by underfunding and other reasons, to reach out to them. I hope that maybe I can use my award money toward something that will be fruitful like that.

Azar Nifisi is the recipient of the 2015 Benjamin Franklin Creativity Award.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)