Olympic Decathlon Medalist Rafer Johnson Dies at 86

He was the first African American athlete to light the cauldron that burns during the Games

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/73/d7/73d784c8-ab9a-4cd5-b360-34ec266816f3/20152231ab002web.jpg)

Editor's Note, December 3, 2020: Olympian Rafer Johnson died in Los Angeles on Wednesday, according to a statement from UCLA and USA Track & Field. The decathlon champion was 86. Read more about his life—and his contributions to the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture—below.

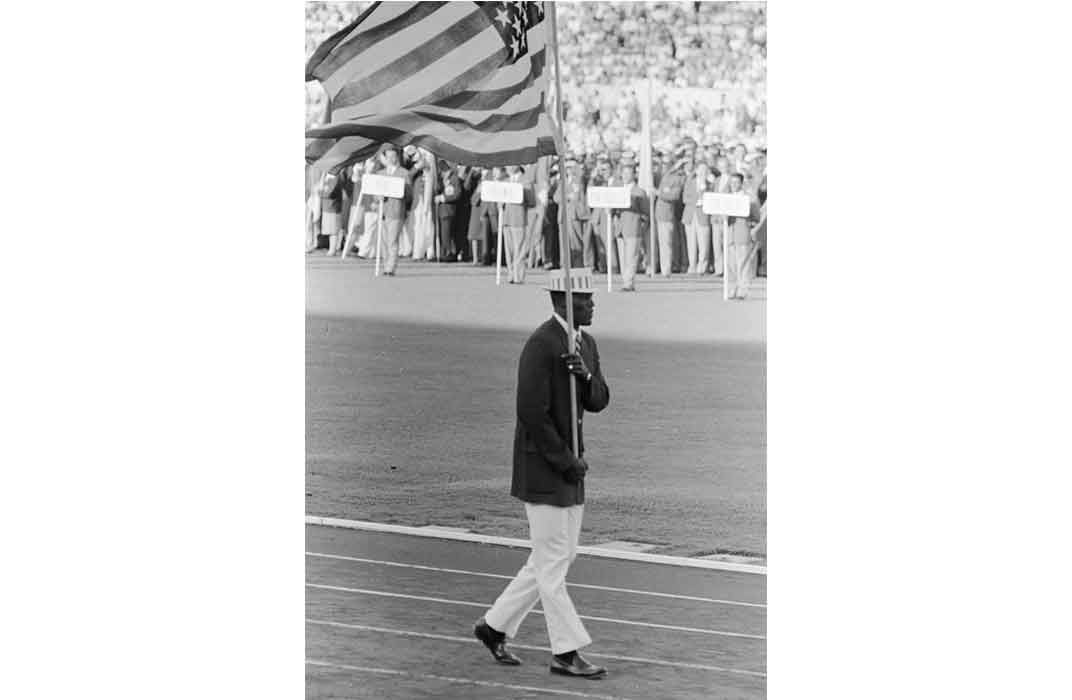

The life of Olympian Rafer Johnson is filled with moments of pride. The 82-year-old Californian won two Olympic medals in the decathlon, was named Athlete of the Year by both Sports Illustrated and the Associated Press, served in the Peace Corps, is a founder and dedicated supporter of the Special Olympics Southern California, and carried the American flag in the 1960 Opening Day ceremony for the Olympic Games in Rome.

In 1968, Johnson and football player Rosey Greer were among a group of men who subdued Sirhan Sirhan moments after he fatally shot Senator and Presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy.

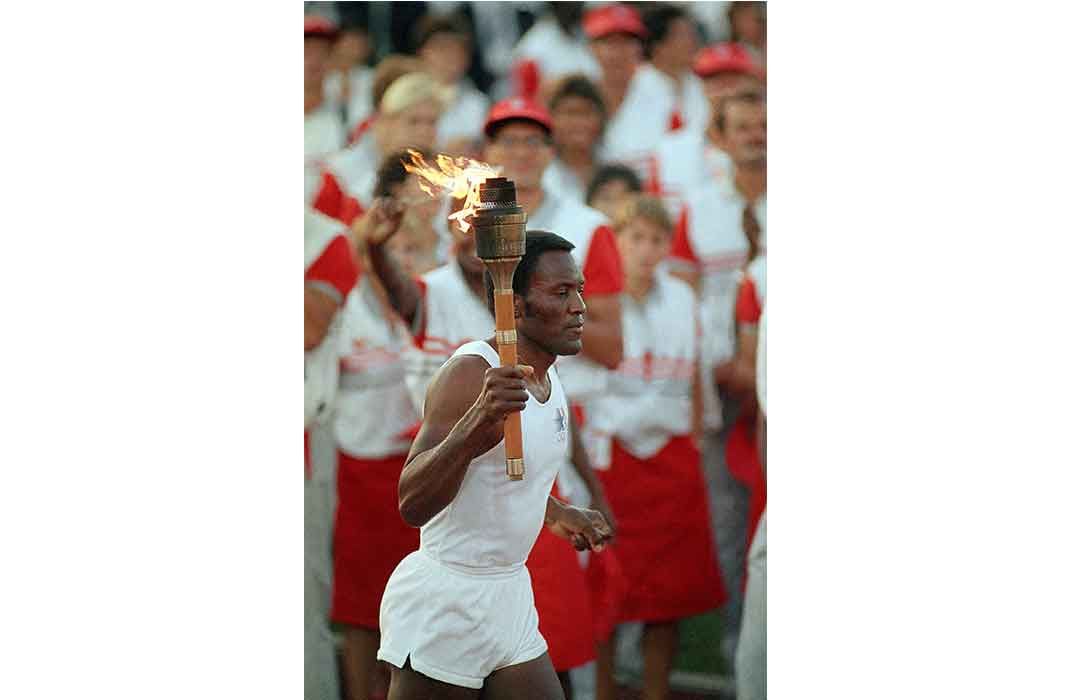

Johnson also carried the torch during the Opening Day ceremonies for the Games held in Los Angeles in 1984. In the grainy video (below), Johnson can be seen running majestically up a long, steep flight of stairs, torch held proudly aloft in his right hand. At the top of the stairs, he turns to face the capacity crowd, and raises the torch even higher to cheers from the audience. Johnson then reaches up, touches it to a pipe that ignites the Olympic Rings and flames roar forth from the cauldron at the top of a tower above the Los Angeles Coliseum.

He was the first African-American to have the honor of lighting the cauldron that burns during the Games, and says that made the ceremony particularly special for him.

“It was one of the proudest moments of my life,” says Johnson, “in knowing that I was in a position representing my country among thousands of athletes representing their country. I thought it was a community of friendship, and I love representing my country.”

“It was something that you see in books, and you hear people talk about the Olympic Games and the opening ceremonies and how wonderful they felt at being part of what was going on at that moment,” Johnson recalls. “I was very, very proud. It was a moment that I will never forget.”

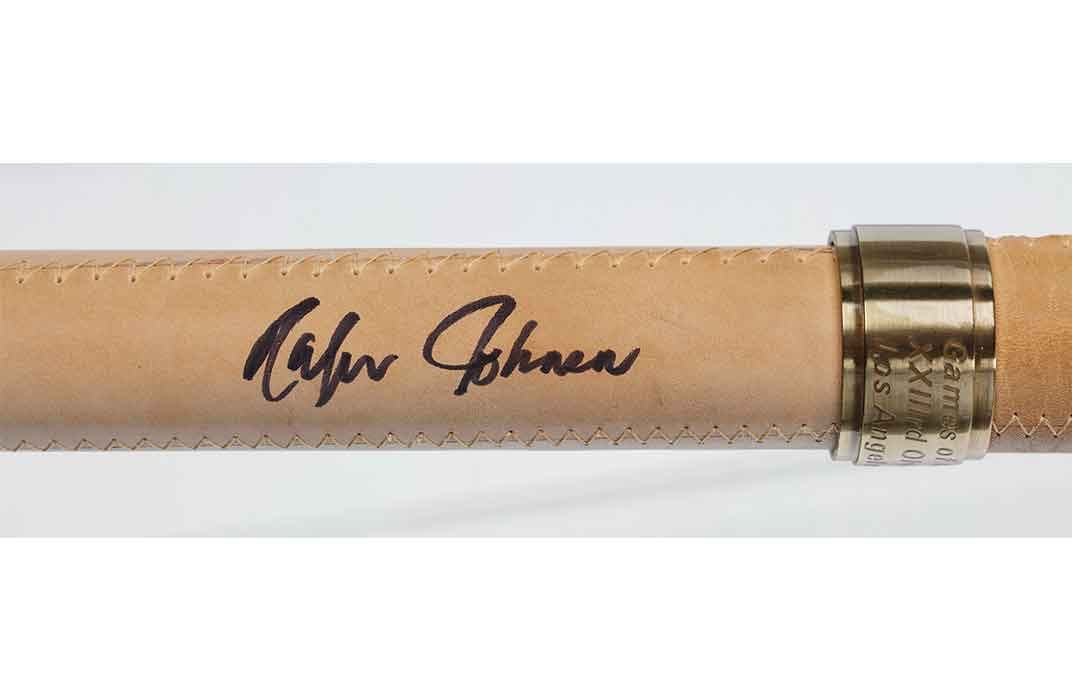

Johnson has donated the metal torch with a leather covered handle that he carried that day to the Smithsonian National Museum for African American of History and Culture, as well as the shirt, shoes and shorts he was wearing when he lit the Olympic Flame.

“I think that if you, if we, if any of us have an opportunity to see what in a sense was accomplished by others, I think it is inspiring,” Johnson says.

The consummate athlete and ambassador for peace and cooperation also broke barriers in Rome, when he was the first black man to carry the American flag during any Opening Ceremony. That same year, 1960, Johnson won gold in the decathlon at the Olympics and, in an earlier event, set a new world record, which he had also done in 1958 and before that in 1955 at the Pan-American Games. At the 1956 Games in Melbourne, he won the silver medal in the same event.

The museum’s sports curator Damion Thomas calls Johnson an important figure and a symbol of the amateur athlete in the 1950s. Thomas says Johnson is someone who embodies all of the ideals Americans associate with sports: teamwork, character and discipline.

“Being the first African-American to carry the (Olympic) flag is a testament to how highly his fellow athletes thought of him,” Thomas explains. “The traditional custom was . . . that the Olympian who had competed in the most Olympics would carry the flag in. It was about seniority. But in 1960 the Olympic athletes broke protocol and chose Johnson.”

Thomas notes that Johnson was already known as a man who built bridges, and became a symbol for intercultural exchange after a 1958 USA-Soviet track meet in Moscow, and it is a distinction Johnson still carries today.

“Johnson was someone who was able to develop relationships with people from different countries and different racial groups, and use sports to bridge culture,” Thomas says. “It became essential to his popularity, and it is how he became a symbol for a bright future for race relations.”

Thomas points to Johnson’s close relationship with the Kennedys as evidence of that. Not only did the star athlete work on Robert F. Kennedy's 1968 presidential campaign, in that same year he attended the first Special Olympics competition, conducted by founder Eunice Kennedy Shriver. The very next year, Johnson and a group of volunteers founded the California Special Olympics.

“It might be fair to say that Johnson became one of the most prominent black members of (President) John Kennedy’s Camelot, this idea that we were in a new frontier of race relations,” Thomas explains. “He worked with Shriver on the Special Olympics; he was with Robert F. Kennedy–that’s how close he was in access to the Kennedy family. He was one of the few African-Americans to be that closely aligned with the Kennedys. The same graceful elegance and youthful charm we associate with the Kennedys we associate with him as well.”

Asked what it was like to be an African-American man with the ear of the Kennedys, Johnson recalls them as a family that looked for how an individual could make a contribution, and not always feel that someone owed you something.

“Yes we needed some changes, but what we had to do was be the best that you could be,” Johnson says, adding that he enjoyed working with the Kennedys whenever he could. He was also happy to be involved with the Special Olympics, because he was able to help a group of men and women who had never had the chance to be on the field of competition.

“I really appreciated in this case what Shriver was working for, but also the family as a whole,” Johnson says thoughtfully. “There were people who had very little or nothing to do in our communities. … It’s important that we work with people, and give them the opportunity to be boys and girls and men and women who themselves can make a contribution.”

Johnson grew up in Kingsburg, California, and for a while, his family was among the few blacks in town. A junior high school there was named for him in 1993. He was proficient in many sports in high school, ranging from football to baseball and basketball, and he also competed in the long jump and hurdles. He was elected class president in both junior and high school, and also at his alma mater, UCLA.

Johnson has also been a sportscaster and prolific actor, appearing in several motion pictures including the 1989 James Bond film License to Kill, and in several television series including "Lassie," "Dragnet," "The Six Million Dollar Man" and "Mission: Impossible." He agrees with historians who think of him as using sports to help change the way people view African-Americans.

“In 1956, I was approached along with other athletes about not competing in the (Olympic) games because of what was going on in our country. It was obvious that people of color had some tough times going to school, getting jobs and getting an education, that was obvious,” Johnson remembers. “I chose to go, and not stay home. . . . My feeling was that, what you want to try to do, which I felt I accomplished in that gold medal run, was to be the best that you could be and that would have more effect I thought on the problems and situations back here at home. I thought I could just come home and be involved in those kinds of activities that would make it better for all of us.”

Johnson believes he has helped accomplish that, partly through his representation of his nation and race on a world stage, and also to give people the idea that if they simply sit and talk, work and play together, they could think about how things ought to be.

“It was important for me to be involved in the process that gave all of us the opportunity to think in a positive way. So I was involved in activities that made me feel good about my contribution, and I could obviously see it was doing all of us some good,” Johnson says, adding that it not only helped change the way people think of African-Americans, but it also helped change the way “people think about anyone that’s different than them.”

Curator Damion Thomas says that’s one of the stories the museum hopes to tell with Johnson’s artifacts, which will be displayed in a room along with Olympic sprinter Carl Lewis’ medals, and name plates for every African-American who has won a medal during the first hundred Olympic Games. He says the museum will also tell the stories of two very different black Olympic torch lighters—Johnson and Muhammad Ali.

Ali, Thomas notes, was someone who challenged American society and American ideas—particularly as related to race. Johnson, he says, is a man who would find common ground and find ways to work with people who were different and who held different beliefs than Johnson did. Both strategies have been used as tools to fight for greater rights and equality.

“African-Americans have used sports as a way to challenge ideas about the abilities of blacks, both athletically and off the playing field as well,” Thomas says. “When sports became a part of the federal education system . . . there was this idea that sports and competition helps develop leaders and it helps you with your cognitive ability. . . . That’s why sports became a placed for African-Americans. If it can challenge ideas about African-American physical abilities, it can challenge other ideas about African-Americans as well.”

Johnson says race relations today are better than they were in the 1950s, but they’re not anywhere near what they should be.

“It’s like having part of the job done. . . . We still have people suffering, people who need help, people who need a good education and a good job,” Johnson says. “I think if we work together, all of us, every race, every color, and take our opinions and put them together, there’s a better chance that we could live in harmony not only at home but around the world.”

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture opens September 24 on the National Mall in Washington, DC.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)