Ancient Popcorn Unearthed in Peru

New discoveries indicate people were eating our favorite movie snack far longer ago than we thought

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120127110004Popcorn-Map-small.jpg)

Popcorn dates pretty far back—way earlier than Orville Redenbacher—according to a study published last week. The paper, which appeared in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and was co-authored by Dolores Piperno, curator of New World archaeology at the Museum of Natural History, reveals that archaeologists have unearthed a number of corn samples from a pair of Peruvian excavation sites. Several of the specimens indicate that among many uses the ancient Peruvians found for the maize was one we still know well today: popcorn.

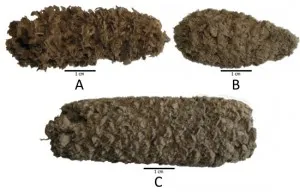

The samples include corncobs, husks and stalks, and date to 6,700 to 3,000 years ago, making the discovery the oldest corn sample ever found in South America, says Piperno. “Corn was first domesticated in Mexico nearly 9,000 years ago from a wild grass called teosinte,” she says. “Our results show that only a few thousand years later corn arrived in South America, where its evolution into different varieties that are now common in the Andean region began.”

The excavation sites, Paredones and Huaca Prieta, are located in a climate that allows such samples to be preserved for a long time. “The sites occur in a very, very arid climate, the coast of Peru, where it almost never rains,” Piperno says. “Those kinds of conditions are particularly good for preserving things, because it’s humidity that affects the preservation of plant remains over time.”

Although there had been previous discoveries of microfossils—such as starch grains—finding entire cobs provides valuable information. “Microfossils give an excellent picture of if they’re eating corn, if corn is present, but what was missing was the morphological detail,” says Piperno. “This site provided actual cobs, information on the sizes of the cobs, and what they look like.” These findings will help researchers trace the early domestication of corn from teosinte, a complicated transformation that occurred thousands of years ago.

The samples indicate that the inhabitants of the site consumed the maize in several different ways—apart from popcorn, they consumed corn flour—but that it was still not a common food at the time. “It was probably a fairly minor component of the diet, because despite the very good preservation, not many cobs were found,” Piperno says.

How did the corn travel all the way from Mexico, its birthplace, to Peru, thousands of miles away? “People just passed it along,” says Piperno. “Farmers like to exchange goods and ideas, so it was probably just passed from person to person, from farmer to farmer.”

Got a burning question about popcorn or some other zany topic? We invite you to submit questions to our new reader forum, Ask Smithsonian. Each month, we’ll select a handful of reader-submitted questions to publish in Smithsonian magazine with answers from the Institution’s experts.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)