Air and Space Curator: The Wright Brothers Were Most Definitely the First in Flight

Aeronautics curator Tom Crouch says yes, despite claims that a German immigrant named Gustave Whitehead may have beat them

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130318034045flight-crop.jpg)

Last week, the British aviation publication Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft declared that the Wright brother’s historic 1903 flight at Kitty Hawk was not the first to achieve sustained, heavier-than-air, controlled flight, but gave the title instead to aviator Gustave Whitehead of Bridgeport, Connecticut, who purportedly flew his craft two years early. The journal’s editor cites the website of an Australian research John Brown and declares the case solved, writing: “The Wrights were right; but Whitehead was ahead.”

The National Air and Space Museum, which has held the Wright Flyer in its collections since 1948, has been challenged over the decades by a number of Whitehead enthusiasts, but have found all claims wanting. Complicating the issue is a contract held by the Smithsonian Institution with the Estate of Orville Wright, which is often cited as “evidence” that the Smithsonian Institution is unable or unwilling to declare any other first in flight contender. The contract stipulates that the museum would lose custody of the Wright Flyer should it ever state that another aircraft was first in flight. Curator of aeronautics and Wright biographer Tom Crouch has long studied the Whitehead claims and today, finds no merit in this most recent argument. The language in the contract, Crouch points out, is related to another Wright competitor, the Aerodrome built by the Smithsonian’s third secretary S.P.Langley (but that’s another story.) Of the contract, Crouch writes: “I can only hope that, should persuasive evidence for a prior flight be presented, my colleagues and I would have the courage and the honesty to admit the new evidence and risk the loss of the Wright Flyer.” Crouch has written the following to address the current claim.

John Brown, an Australian researcher living in Germany, has unveiled a website claiming that Gustave Whitehead (1874-1927), a native of Leutershausen, Bavaria, who immigrated to the United States, probably in 1894, made a sustained powered flight in a heavier-than-air machine on August 14, 1901, two years before the Wright brothers. The standard arguments in favor of Whitehead’s flight claims were first put forward in a book published in 1937, and have been restated many times. With a new wave of interest in the Whitehead claims, the time has come for a fresh look.

What are the claims?

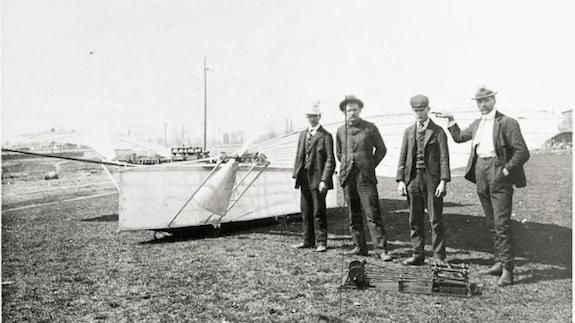

On August 18, 1901, Richard Howell, a reporter for the Bridgeport Sunday Herald, published an account of the early morning flight of August 14, in which he claimed that Whitehead traveled half a mile through the air at a maximum altitude of 50 feet. Thanks to the rise of newswire services, the story was picked up by a large number of American newspapers and a handful of overseas publications. In two letters published in the April 1, 1902, issue of American Inventor, Whitehead himself claimed to have made two more flights on January 17, 1902, on the best of which he said that he flew seven miles over Long Island Sound. During the months that followed, additional widely circulated stories reported that Whitehead was organizing a company to build airplanes and that he intended to enter one of his machines in the aeronautical competition being planned for the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition to be held in St. Louis in 1904. While his company failed and he did not fly at the St. Louis Fair, Whitehead did build a number of flying machines for other enthusiasts, several of whom were on view at the Morris Park air meet in November 1908. None of the post-1902 Whitehead powered machines ever left the ground, although he did build aeronautical motors that powered aircraft designed and built by other fliers.

What is the evidence?

The original Bridgeport Sunday Herald story, supposedly an eyewitness account, sounds impressive. It is important to note, however, that the editor did not rush into print with a front page story. The article appeared on page five, four days after the event, in a feature story headlined with four witches steering their brooms through the word–flying. In the story Howell notes two witnesses other than himself, James Dickie and Andrew Cellic. When an interviewer returned to Bridgeport to research the claims in 1936, he could not find anyone who remembered Cellic. He did find Dickie, however. “I believe the entire story of the Herald was imaginary and grew out of the comments Whitehead discussing what he hoped to get from his plane,” the supposed witness commented.

“I was not present and did not witness any airplane flight on August 14, 1901, I do not remember or recall ever hearing of a flight with this particular plane or any other that Whitehead ever built.”

Between 1934 and 1974 researchers supporting Whitehead’s claim interviewed 22 additional persons who said that they had seen him fly at one time or another during the period 1901 to 1902. In this day and age of DNA testing, we have learned that eyewitness testimony given just after an event occurred can be fatally flawed. The witnesses in the Whitehead case were being interviewed about an event that had occurred more than three decades before, by researchers who were anxious to prove that Whitehead had flown.

Many of the individuals who were most closely associated with Whitehead, or who were funding his efforts, doubted that he had flown. Stanley Yale Beach, the grandson of the editor of Scientific American and Whitehead’s principle backer, was unequivocal on this issue.

“I do not believe that any of his machines ever left the ground. . .in spite of the assertions of many people who think they saw them fly. I think I was in a better position during the nine years that I was giving Whitehead money to develop his ideas, to know what his machines could do than persons who were employed by him for a short period of time or those who remained silent for thirty-five years about what would have been an historic achievement in aviation.”

Aeronautical authorities certainly doubted the tale. Samuel Cabot, who had employed Whitehead in 1897, regarded him as “…a pure romancer and a supreme master of the gentle art of lying. ” Cabot told Octave Chanute, a Chicago engineer then widely regarded as the world’s authority on flying machine studies, that Whitehead was “completely unreliable.” Hermann Moedebeck, a German military officer and aviation authority, wrote to Chanute in September 1901, remarking that he believed Whitehead’s “experiences are Humbug.”

Perhaps the strongest argument against the Whitehead claims is to be found in the fact that not one of the powered machines that he built after 1902 ever left the ground. Nor did any of those machines resemble the aircraft that he claimed to have flown between 1901 to 1902. Why did he not follow up his early success? Why did he depart from a basic design that he claimed had been successful? Are we to assume that he forgot the secret of flight?

Then there is the missing photo. In an article describing an indoor New York aeronautical show in 1906, Scientific American noted that: “A single blurred photograph of a large bird-like machine propelled by compressed air, and which was constructed by Whitehead in 1901, was the only other photograph beside Langley’s machines of a motor-driven aeroplane in successful flight.” Another contemporary news article also mentions a photo of a powered Whitehead machine in the air displayed in a shop window. No such photograph has ever been located, in spite of the best efforts of Whitehead supporters to turn one up over the years. I have always assumed that the photo in question was actually one of the well-known photos of un-powered Whitehead gliders in the air.

Researcher John Brown now claims that he has found that photo.

The National Air and Space Museums’ William Hammer Collection contains a photo of the museum’s Lilienthal glider hanging in the 1906 exhibition. A display of photos is visible on the far wall in the image of the glider. While the photos in the photo are indistinct and blurry, it has always been apparent that some of them look like well-known photos of Whitehead craft. Over 30 years ago, I had NASM photographers enlarge the images seen on the wall to the extent possible at that time. Indeed, some of the photos could be identified as known Whitehead images. We could not find an image that looked like a machine in flight, however.

John Brown has used modern techniques to search once again for that photo in the photo, and claims to have found it. Readers can view the result of his research on his website and make the determination for themselves. From my point of view, it does not look anything like a machine in flight, certainly nothing to compare with the brilliant clarity of the images of the 1903 Wright airplane in the air, images that are among the most famous aviation history photos ever taken.

Whatever the anonymous reporter who penned the paragraph on the Whitehead photo at the 1906 exhibit thought, there can be no doubt as to whom the editors of that journal credited with having made the first flight. In an editorial in the issue of December 15, 1906, at a time when the Wright brothers had yet to fly in public, and when their claims to have developed a practical powered airplane between 1903 and 1905 were widely doubted, Scientific American offered one of the first definitive statements recognizing the magnitude of their achievement.

“In all the history of invention there is probably no parallel to the unostentatious manner in which the Wright brothers of Dayton, Ohio, ushered into the world their epoch-making invention of the first successful aeroplane flying machine. . .Their success marked such an enormous stride forward in the art, was so completely unheralded, and was so brilliant that doubt as to the truth of the story was freely entertained. . . .”

Following a thorough study of the Wright claims, the editors of Scientific American “. . .completely set to rest all doubts as to what had been accomplished.” Unlike the case of Gustave Whitehead, a careful investigation proved that Wilbur and Orville Wright had accomplished all that they claimed, and more.

Now, on the basis of biased information and unsupported assumptions offered in the new website, Paul Jackson, editor of Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft: Development & Production, has decided to support the claims of Gustave Whitehead to have flown before the Wright brothers. Like the editors of Scientific American, Mr. Jackson would have been well advised to take a look at the historical record of the case, and not make his decision based on a flawed website. When it comes to the case of Gustave Whitehead, the decision must remain: not proven.