After 50 Years of Song, Dance, Food, Even Hog Calling, at the Folklife Festival, Is It Still Worthwhile?

Recognizing traditional culture in the information age is ever more important argues the director of the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage

Traditional culture permeates our lives. It includes things like what we eat for breakfast, how we greet our family, and how close or far we stand from other people when we encounter them in public places. UNESCO has described traditional culture—or intangible cultural heritage—as the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills—as well as the associated instruments, objects, artifacts and cultural spaces—that individuals, groups and communities recognize as part of their cultural heritage.

Even in the information age, this living cultural heritage plays an enormous role in the choices we make. For example, where does your name come from, who chose it and why? What rituals does your family do day after day, year after year? As a folklorist, I have spent much of my life studying the ritual expressions of African-inspired religions in Cuba, and wrote a book about how rituals change people. The value of rituals and traditions, though, extends beyond the work of cultural anthropologists and folklorists. Song artists, the home chef, even children singing playground chants are collecting and archiving and sharing important ritual cultural expressions.

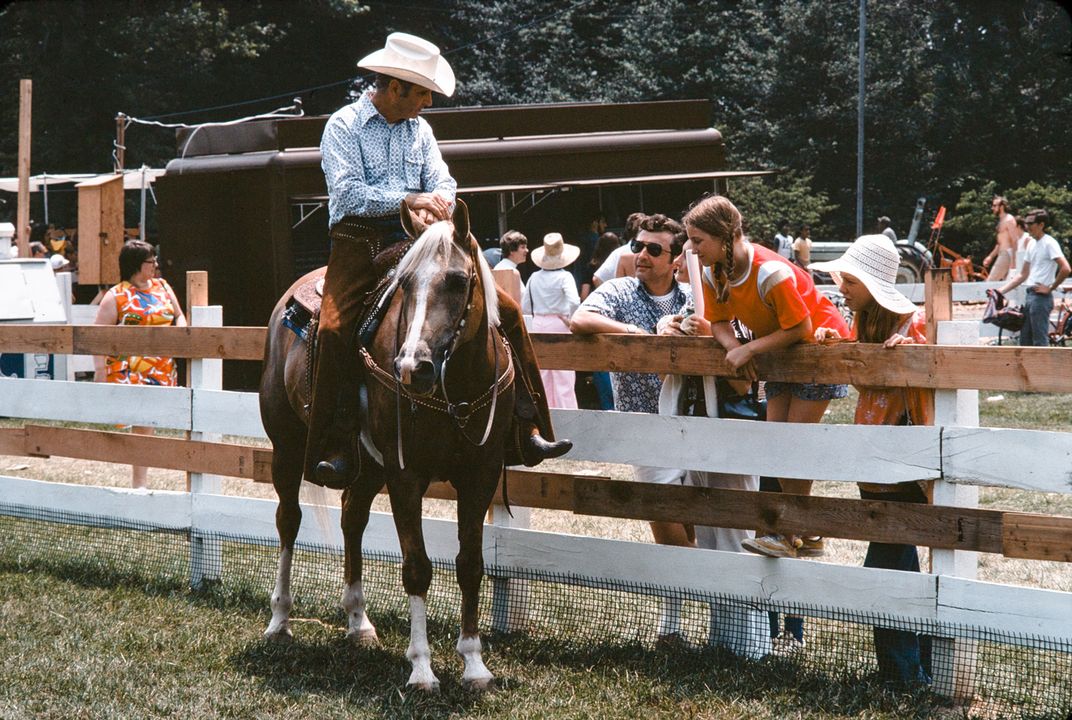

This summer the Smithsonian Folklife Festival celebrates its 50th anniversary with an exploration of circus arts and the impact of migration over generations. The Festival has long played a role in digging deep into the rich diversity of cultural life in U.S. and around the world to seek it out, record it, archive it and put it before audiences here in Washington, D.C. on the National Mall.

Fifty years into this annual summertime bacchanal of tented events that feature the cultural traditions of food, craft, artistry, music, dance, theater, storytelling and even yes, hog calling, why are we still passionate about it? Why does it still matter when so much of modern life is defined by innovation, speed and profit? To answer these questions and to honor the millions of people who have participated, produced and attended the Festival since 1967, I wanted to take this opportunity to reflect on its vital role in our society.

Traditional culture crafts reminds us that everyday people often make extraordinary art in the course of their lives. Culture does not belong only to professional artists, and it does not live only in galleries and museums. Rather, artistic expression lives within and around us all.

Take the example of quilting. In the United States, the tradition of making quilts and handing them down through families has become a major movement. Tens of thousands of people are now involved in quilting. In November 2013, Paducah, Kentucky, was named a UNESCO creative city because of the prevalence of quilting there. Outstanding quilters, such as Carolyn Mazloomi and Mozell Benson, have been honored as National Endowment for the Arts’ National Heritage Fellows.

Traditional cultural expressions bring people together. Whether making music or listening to it, whether building human towers or cooking a family meal, expressive culture unites people in a shared activity where they can experience and reflect upon their lives. Artists and those of us allied with their work have long known that sharing artistic expression creates a strong sense of connection between people, a state that some social scientists call communitas. “Communitas occurs through the readiness of the people—perhaps the necessity—to rid themselves of their concern for status…and to see their fellows as they are,” writes anthropologist Edith Turner. “Communitas is a group’s pleasure in sharing with one’s fellows.” Local musical traditions from garage bands to more distinctive local genres—folk dancers, festival arts, spoken word, storytelling, building arts, and local food practices—bring people together and are all kept vibrant as they are passed from one person to another.

In fact, some arts advocates have explored the intrinsic impacts of experiencing live performance together, and they found that social bonding is a key outcome. This research reinforces what artists, folklorists, and ethnomusicologists have long known: Witnessing an artistic presentation unites people, especially when it celebrates or sustains some aspect of cultural heritage. These expressions usually link language, cultural practices, symbolic places and historical events. Bringing these cultural assets into play allows people to celebrate, reassert and transform their sense of identity.

Traditional art forms can provide not only an economic benefit to some communities but it also fortifies practitioners with a tremendous sense of physical well being. In the Basque Country, the famous traditional delicacy Idiazabal cheese has been made from sheep’s milk for generations. Since the United Nations adopted its Millennium Development Goals, people around the world have been actively exploring how cultural heritage can support the livelihoods of communities around the globe. Many countries have created “denominations of origin” to give a market brand identity to traditional food and wine production. The Spanish state codified the process and ingredients to regulate the quality and geographic origins of Idiazabal cheese, a strategy to valorize this local product in the larger market place.

Similarly, the Self-Employed Women’s Association has organized women in Gujarat, India, to document and share local embroidery and textile arts to provide women with additional sources of income; the women became so engaged in celebrating these traditions that they also developed a museum to highlight the best pieces from their community.

The Urban League has explored how local cultural vitality feeds into community development efforts. This work sought “evidence of creating, disseminating, validating, and supporting arts and culture as a dimension of everyday life in communities” to ensure that community-based cultural expressions factored into efforts to reimagine and revitalize communities across the United States.

The Alliance for California Traditional Arts partnered in 2011 with the University of California, Davis, to study the relationship between participation in community arts and health. Their findings make clear that engaging in traditional art forms improves physical and mental health and provides a wide range of social benefits.

It is common, even today, to hear spirituals sung in homes, churches and political events. These prayer-filled anthems and impassioned vocal performances resonate so deeply, connecting people to a past that is dark with longstanding patterns of exclusion and the drive for freedom from slavery. African American spirituals allowed enslaved people and their descendants to give voice to both the sufferings of their oppression as well as their yearning and hope for better times. These songs traveled with people as they moved out of slavery and worked through Jim Crow and the Civil Rights era to create a more equal and just American society. Traditional culture is a uniquely powerful tool for capturing this zeitgeist, it expresses human aspirations, it empowers civic expression and speaks to a brighter future.

For centuries, artists in search of new creative forms of all kinds have sought inspiration in traditional expressions. Professional artists sometimes incorporating its elements directly and at other times improvising based on traditional cultural forms. So-called “high artists” have borrowed and purloined from the endless resources available to them from traditional culture.

In The Merchant of Venice, William Shakespeare used the folktale motif of the three caskets and in Midsummer Night´s Dream, he sampled from the complex legends of the fairies Oberon and Mab.

In Hungary, the renowned composer Béla Bartók tirelessly documented as an ethnomusicologist the musical traditions of his homeland; and the unique sounds of rural Hungry were transposed within his own musical creations.

In his native Palafrugell, along the Costa Brava near Barcelona, the distinguisted Catalan writer Josep Pla in his masterful book, Gray Notebook, taps into café conversation for material. So important is traditional verbal arts to the literary tradition that both William Butler Yeats and Italo Calvino spent decades documenting, editing and publishing collections of folktales. Similarly, contemporary Cuban visual art overflows with images borrowed from the African-inspired religions there.

At its heart, traditional culture revolves around free expression. Communities keep these practices alive to remind themselves of their origins, their histories and their way forward into the future. Individuals use traditional cultural forms to comment on what is happening around them.

Freedom of speech—to hold and publicly communicate political opinions—long before it makes its appearance in the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution has its origin in the Roman Republic. Many civil libertarians advocate for the more expansive freedom of expression—to seek and share information and ideas, regardless of medium—and the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights’ guarantees freedom of expression to all and assures the cultural rights necessary for dignity and the development of the individual.

Legal scholars like Richard Moon focus on the social nature of expression, how it creates relationships between people who in turn foster new knowledge and new directions for communities large and small. Cultural and artistic expression provides a principal avenue to understand and communicate the most important aspects of our common humanity.

Whether you perform at, or attend, the Smithsonian Folklife Festival; whether you create a wonderful meal for the people you love, or whether you learn from your grandfather how to make a bird call, you are keeping alive cultural traditions and communicating important ideas and values about who you are and where you are headed. To let this communication die without the recognition it has received over the past five decades at the Folklife Festival would be a violation of our identity as people. Supporting it is a simple but powerful act of freedom.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Mason_Michael-12012.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/70/ec/70ecf16e-60de-4edb-aab7-bbb55b769c09/faf1972_0834.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/05/49/05493d15-9b83-4511-a039-f6c95bb5ae21/sff2015_jw_7-03_0009.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Mason_Michael-12012.jpg)