Vladimir Nabokov’s Butterfly Drawings Take Flight in This New Book

A little-known fact: The author of “Lolita” was also an avid lepidopterist

Vladimir Nabokov might be best known as a novelist, specifically as the author of Lolita, but what many might not know is that one of his deepest passions was studying butterflies.

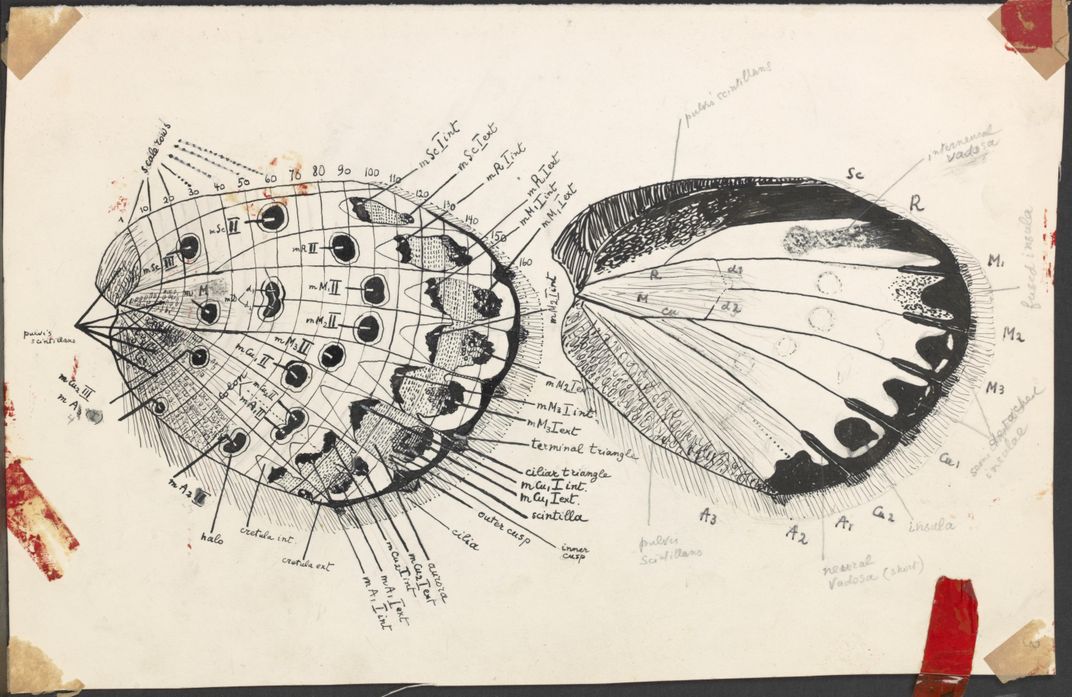

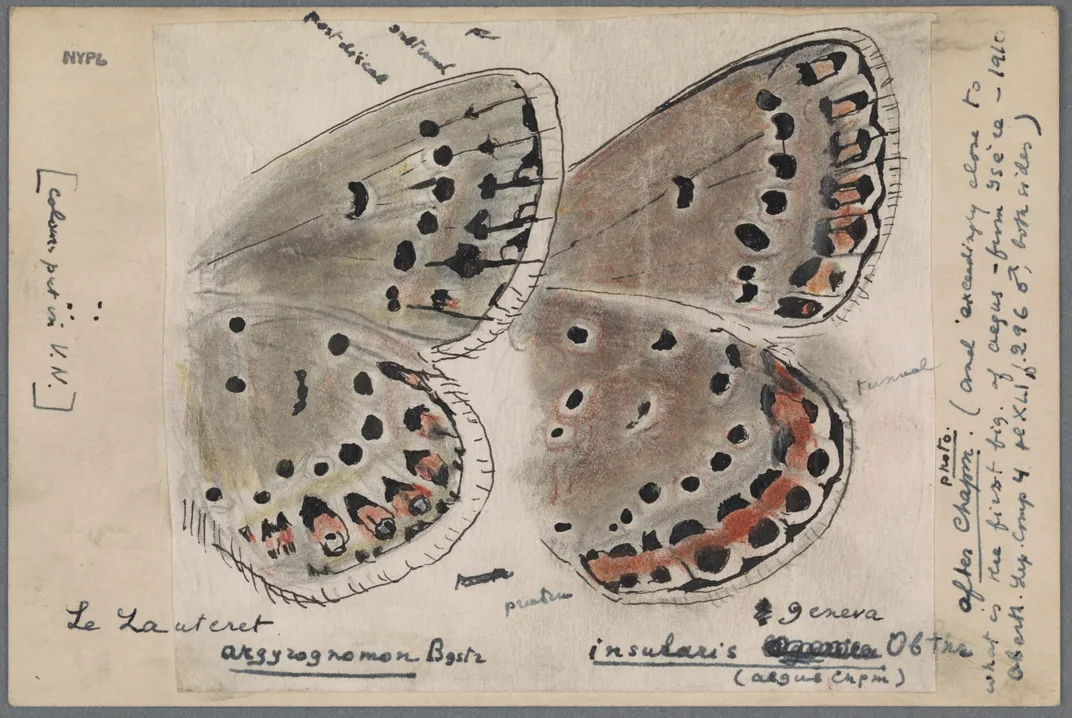

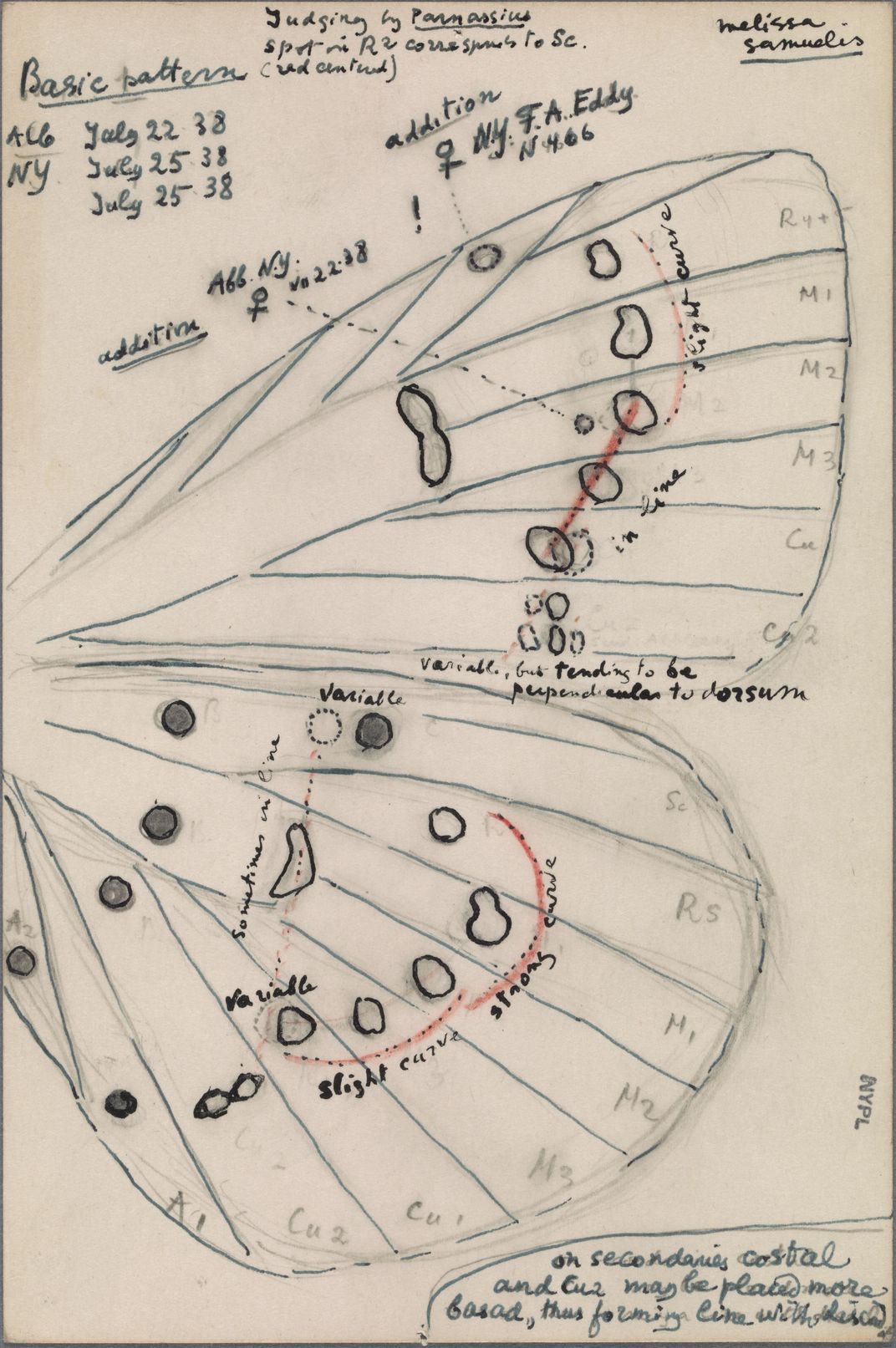

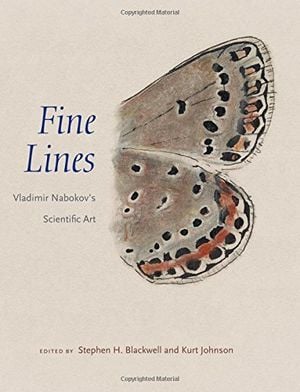

Now, a new book from Yale University Press honors his dedication to the delicate creatures. The book, Fine Lines, is a collection of more than 150 of his scientific illustrations of butterflies, rivaling John James Audubon in their detail.

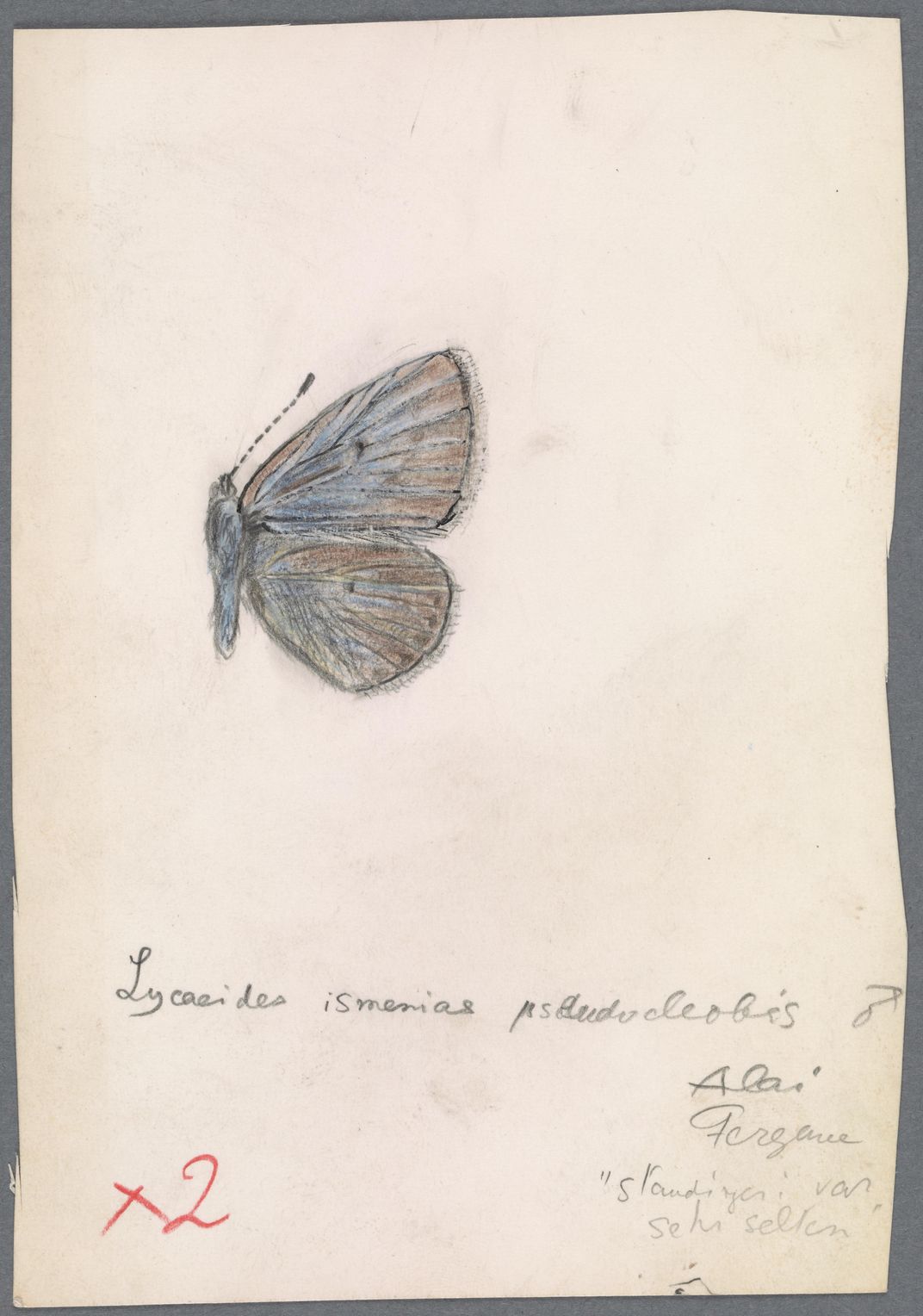

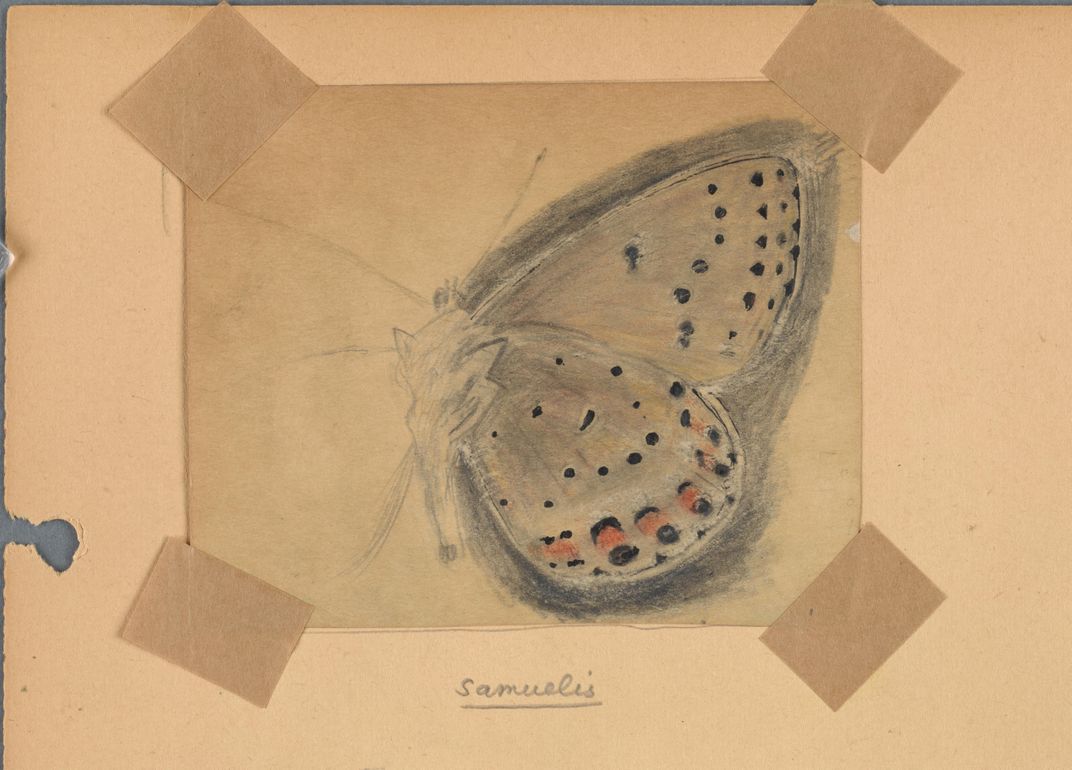

Nabokov began collecting butterflies when he was seven years old and continued his study of the insects his entire life. He dreamed of naming a butterfly since he was a child, Elif Batumen writes for the New Yorker. Thanks to his diligence, he named several, most notably a species called the Karner blue (Lycaeides melissa samuelis).

Even so, Nabokov’s studies sometimes proved controversial. In Fine Lines, the editors Stephen Blackwell and Kurt Johnson lament that Nabokov was never taken seriously by professional scientists and entomologists because of his literary career.

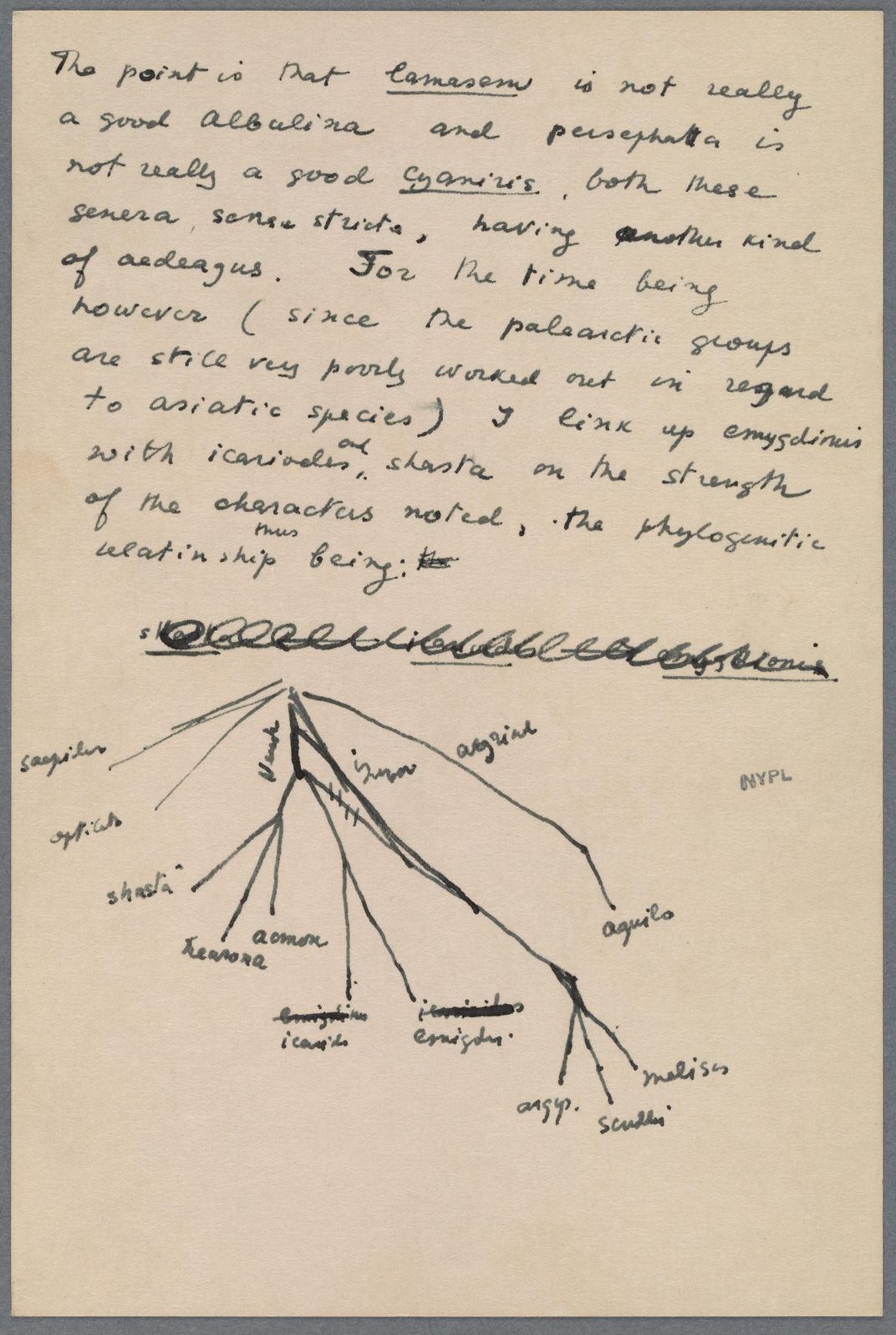

Take, for example, Nabokov’s hypothesis of the evolution of a group of butterflies called “Polyommatus blues.” After making many detailed observations of these North American butterflies, Nabokov proposed that the species had evolved from an Asian species over millions of years as they traveled to the Americas in waves.

For decades, scientists chided this idea, and few lepidopterists took him seriously, Carl Zimmer wrote for the New York Times. In 2011, however, a group of scientists decided to test his proposal with DNA analysis and discovered, to their astonishment, that Nabokov had been right all along.

“I couldn’t get over it—I was blown away,” Naomi Pierce, one of the study authors, told Zimmer at the time.

Nabokov once called literature and butterflies “the two sweetest passions known to man,” according to The Guardian, and in many ways his two loves informed each other. Over the course of years, Nabokov and his wife, Véra, racked up thousands of miles crisscrossing the U.S. in search of butterflies, during which time he began making notes that would later turn into Lolita, Landon Jones writes for the New York Times:

His travels over the years took him from the Bright Angel Trail in the Grand Canyon to Utah, Colorado and Oregon. But one of the best places to find many different species of butterflies congregating at one time was at nosebleed-high altitudes along the Continental Divide in Wyoming. Along the way the shape of the novel took root, and he started to take notes during his butterfly hunts and write them up back in his motel rooms.

Nabokov’s contributions to the study of butterflies may have been small compared to his literary accomplishments, but his appreciation for the delicate beauty of the creatures may have been the magic that gave many of his novels wings.