To Understand How the Supreme Court Changed Voting Rights Today, Just Look at This Map

Today the Supreme Court of the United States decided 5 to 4 that one major section of the Voting Rights Act was unconstitutional

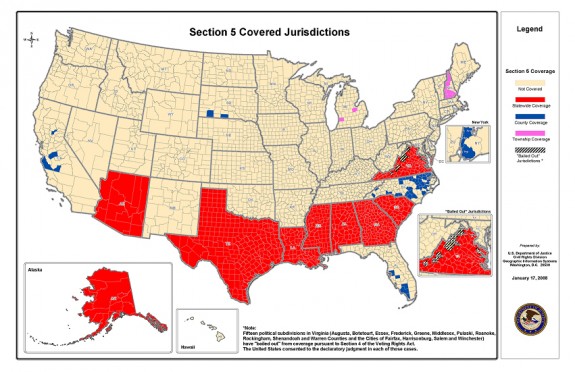

These are the states and regions affected by the special restrictions on voting procedures of Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Photo: Department of Justice

In 1965, the government under President Lyndon B. Johnson passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, a bill that imposed special restrictions on how some states could run their elections. It was a law passed to solve a problem: in certain parts of America, a history of racial bias prevented equal voting for all—particularly African Americans living in the South. Today the Supreme Court of the United States decided 5 to 4 that one major section of that Act was unconstitutional.

The decision leaves the Act’s potential to impose special restrictions intact, but in practice those restrictions now apply to no one. In all the jurisdictions in the map above, voting laws will no longer be singled out for extra scrutiny—unless Congress updates the law with a new system to identify places in need of special attention.

Today’s decision by the Supreme Court affects how one section of the act, Section 5, is applied. Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 ruled that some U.S. states and counties had to seek special permission from “the Justice Department or a federal court before making any voting law changes,” says the Washington Post. The law was intended to prevent these regions from passing racially-restrictive voting procedures. Another section of the Act, Section 4, decided which jurisdictions Section 5 applied to. It was Section 4 that was struck down today by the Supreme Court. Although the restrictions of Section 5 still technically exist, they don’t actually apply to anyone right now.

Bloomberg details the history of the Act, and its origins under President Johnson during the civil rights era of the 1960s.

The need to grant all Americans equal access to the ballot, Johnson said, was brought into relief by the violence in Selma, which he likened to Lexington and Concord, the Massachusetts cities where battles ignited the American Revolutionary War, and Appomattox, the Virginia site of the Civil War surrender of Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s forces to the Union.

While acknowledging that other aspects of the civil rights movement were “very complex and most difficult,” Johnson said that “there can and should be no argument” about the right to vote. “Our mission is at once the oldest and most basic of this country,” Johnson told lawmakers, “to right wrong, to do justice, to serve man.”

<iframe frameborder="0" height="450" src="//commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Remarks_on_the_Signing_of_the_Voting_Rights_Act_(August_6,_1965)_Lyndon_Baines_Johnson.ogv?embedplayer=yes" width="600"></iframe>

More from Smithsonian.com:

“For All the World to See” Taking Another Look at the Civil Rights Movement

Freedom Rides: A Civil Rights Milestone

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/smartnews-colin-schultz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/smartnews-colin-schultz-240.jpg)