The Quest to Better Describe the Scent of Old Books

Describing a unique smell just got easier thanks to a pair of olfactory detectives

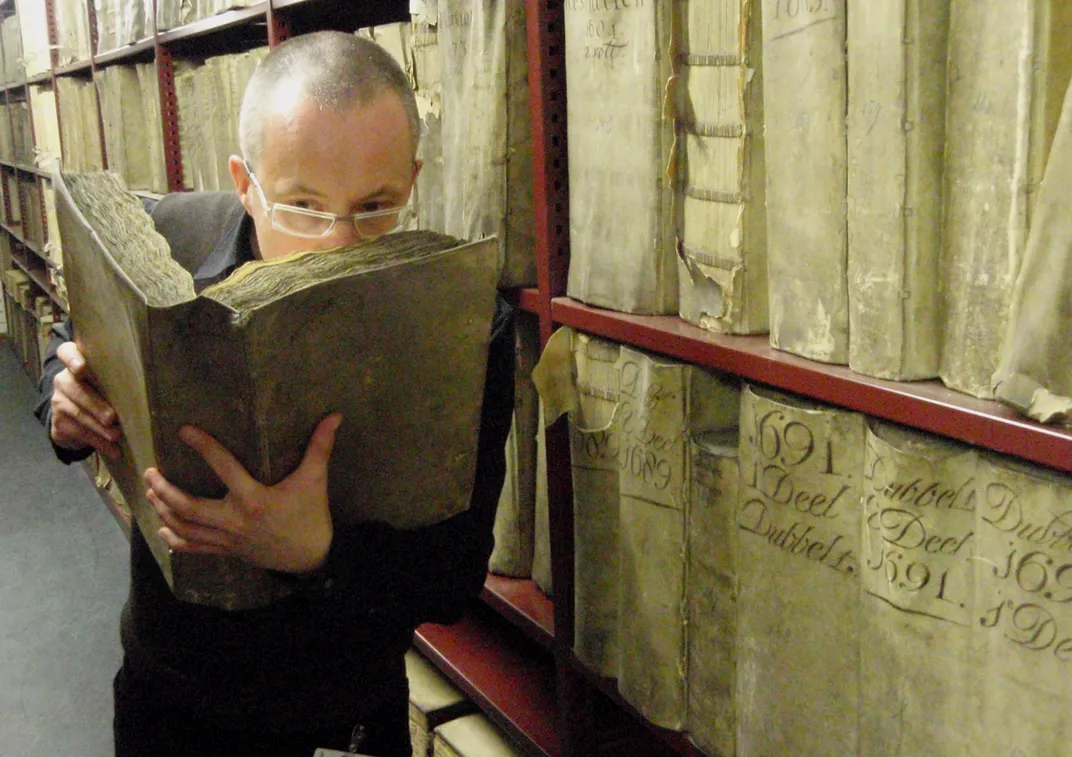

You’ve just stepped into a very old library. What’s the sensory experience like? Dust could shimmer in the light; silence fills your ears. But the sense most people notice first is smell—the scent of old books prickling your nose.

Describing that smell, however, is a challenge. And generic adjectives will likely be of little use to future generations of historians trying to document, understand or reproduce the scent of slowly decomposing books. Now, that task may have just gotten easier thanks to a tool called the Historic Book Odor Wheel.

In a new study published in the journal Heritage Science, researchers tried to develop guidelines for characterizing, preserving and possibly even recreating old smells. To do this, they used one of the most recognizable smells of the past: old books.

In the lab, the team, did a chemical analysis of the volatile organic compounds, or VOCs, emitted by books. Since paper is made of wood and is constantly decomposing, it releases chemical compounds into the air that mix together to form a unique scent. They captured those compounds and used a mass spectrometer to analyze its chemical signature.

Such information can help conservators better understand the condition of and potential threats to a book, explains Matija Strlič, co-author of the paper. “Smells carry information about the chemical composition and the condition of an object,” he says.

But the heritage science team from the University of London wanted to also take their work out of the lab. “When we talk to curators of historic libraries, they point out that smell is the first really important reaction between the visitor and the library itself,” Strlič tells Smithsonian.com. So to learn more about that first interaction, they took their research on the road.

With the help of visitors to the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery in England and a panel of library smellers at the historic Wren Library at St. Paul’s Cathedral, the team conducted a sensory analysis. They presented museumgoers with eight smells—one of which was an (unlabeled) historic book scent and seven were decidedly non-bookish, such as eau de fish market and coffee. The researchers then had participants answer a questionnaire, including a question asking descriptors of of the historic book smell.

The group of library smellers were asked to abstain from the use of scented products and eating 30 minutes before the sniff test. Upon entering the library, participants described the smells using a form that provided 21 descriptors, including "almond" or "chocolate," and the option to fill in their own descriptions.

When museum sniffers described the book smell, they most frequently used words like “chocolate,” “coffee,” and “old.” Library smellers, however, selected words like “woody,” “smoky” and “earthy” from the list, and described the smell’s intensity and perceived pleasantness. Next, the team used all of the information they collected to create the Historic Book Odor Wheel, a descriptive wheel kind of like tools used to characterize the flavors of coffee or wine.

For co-author Cecilia Bembibre, the project was not just a chance to inhale some of her favorite aromas, but to figure out how to best characterize—and one day preserve—smells. “It’s not the whole picture, but it starts building communicable data,” she tells Smithsonian.com. “This starts a conversation with philosophers, scientists, anthropologists, technologists, and the public itself about what we need to describe a smell.” Those conversations, says Bembibre, will lead to a better way to monitor a baseline smell, capture and describe a smell, and perhaps some day reproduce it in a lab.

It’s heady stuff, but work that’s already being put to good use in England. The researchers tell Smithsonian.com that they are working with Knole House, a historic house that’s been in the same hands for generations, to preserve and recreate smells. When writers like Virginia Woolf stayed at the house, they documented how it smelled—and that information can be used along with current measurements and sensory analyses to help preserve its odor for generations. This work is still in its infancy, says Bembibre, but one day odor could be used more by museums and historians to reconstruct a past we can no longer smell.

So what are some of the smell scientists’ favorite odors? For Bembibre, it’s rain. For Strlič, it’s the memory of his grandmother cooking. But both agree that there’s just something special about books—a love that has sparked an entire era of their careers and, perhaps, a way to make history even more alive.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)